Prescription Drug and Controlled Substance Abuse

Opioid Diversion and Best-Practice Prescribing

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

This 3-contact-hour continuing education course shows nurses and other healthcare practitioners how prescription drug abuse can be prevented and why it is so common. Learn more about the current opioid and prescribed drug abuse epidemic and challenges in managing chronic pain for better patient outcomes. Meets Florida, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Texas requirements.

Note: This course is also available as part of a package. See Florida Nursing CEU Bundle - 24 Hours

Course Price: $30.00

Contact Hours: 3

Pharmacotherapeutic Hours: 0.5

Course updated on

April 23, 2025

"Very informative. Links for resources are very helpful." - Jill, APRN in Pennsylvania

"Thank you for the course. I would like to also thank you for having someone available to speak to me when I have any questions." - Barbara, APRN in Florida

"Very Informative. I appreciated the review of CDC guidelines." - Margaret, NP in Illiniois

"Thank you for this course. It is extremely helpful." - Susan, NP in Missouri

Prescription Drug and Controlled Substance Abuse

Opioid Diversion and Best-Practice Prescribing

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will better understand best-practice prescribing of controlled substances, how to prevent drug diversion, and how to administer an opioid antagonist. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Identify components of responsible opioid prescribing practices and reasonable standards of care.

- Discuss the CDC guidelines for safe prescribing of opioids.

- Explain strategies designed to prevent prescription drug misuse and diversion.

- Recognize chemical dependency and impairment in the workplace

- Describe considerations for the use of the opioid antagonist naloxone.

- Discuss nonpharmacologic interventions for pain.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Overdoses are the leading injury-related cause of death in the United States. According to provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics, an estimated 107,543 people died from drug overdoses in 2023, with 81,083 (75%) of those deaths involving an opioid. This represents a decrease of 3% from estimated deaths in 2022 (CDC, 2024a).

The crisis is far from resolved. Data indicate that a large number of individuals continue to misuse prescription drugs. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health estimates that in 2023:

- 8.6 million people ages 12 and older misused prescription pain relievers.

- 828,00 people ages 12 and older misused prescription or illegally made fentanyl.

- 48.5 million people ages 12 and older had a substance use disorder in the past year. (SAMHSA, 2023a)

One of the biggest challenges in healthcare practice is providing safe and appropriate pain care without contributing to the crisis of prescription drug misuse, drug diversion, and drug overdose deaths. Nurses in particular are in a unique position to address this problem since they care for more patients than any other health profession. Nurses who understand the risks associated with prescription drug abuse will be better prepared to identify and intervene with patients and colleagues who may be at risk.

COMMONLY USED TERMS

- Illicit drug use

- Use and misuse of illegal and controlled drugs, including any use of marijuana or hashish, cocaine, crack, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, as well as misuse of prescription pain relievers, tranquilizers, stimulants, and sedatives; excludes use of over-the-counter drugs

- Opioids

- Drugs that act on opioid receptors in the spinal cord and brain to reduce the intensity of pain-signal perception intensity; include the illegal drug heroin, illegally made fentanyl, and pain medications available legally by prescription, such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, prescribed fentanyl, and others (CDC, 2024b)

- Opioid use disorder (OUD)

- A problematic pattern of opioid use that causes significant impairment or distress; diagnosed based on specific criteria such as unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use or use resulting in social problems and a failure to fulfill obligations at work, school, or home, among other criteria; preferred term over opioid abuse or dependence or opioid addiction

- Overdose

- Injury to the body (poisoning) that happens when a drug is taken in excessive amounts

- Prescription drug misuse (or nonmedical use of prescription drugs)

- The use of prescribed medications in any way not directed by a doctor, including use without a prescription; use in greater amounts, more often, or longer than instructed; use to get high; diversion; concurrent use of alcohol, illicit substances, or nonprescribed controlled medications; or use in any other way not directed by a doctor

- Prescription drug diversion

- Obtaining or using prescription drugs illegally

- Substance use disorder (SUD)

- A cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiological symptoms indicating that the individual continues using the substance despite harmful consequences or impaired ability to function in day-to-day life; can cause changes in brain function and distorted thinking and behaviors; preferred term over addiction or substance abuse

(Becker & Starrels, 2024; CDC, 2024b, 2024c; APA, 2024; SAMHSA, 2023a)

RESPONSIBLE OPIOID PRESCRIBING AND STANDARDS OF CARE

The serious and deadly consequences of the opioid crisis prompted the medical community to reevaluate chronic pain treatment and prescribing practices. Responsible prescribing involves individual prescribers following best practices and adhering to reasonable standards of care to balance the risks and benefits of opioid pain management for each patient. Three important components to responsible prescribing include:

- Thorough patient evaluation, including risk assessment

- Treatment plan design that incorporates functional goals

- Periodic review and monitoring

Best practices are also described in evidence-based guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain released in 2016 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and updated in 2022 (Dowell et al., 2022) (discussed later in this course).

Patient Evaluation and Risk Assessment

A thorough patient assessment is critical prior to prescribing opioid medication for chronic pain. It is important to properly diagnose the condition to determine if opioid medication is an appropriate treatment. A comprehensive pain assessment includes a history of the pain, behavioral observations, past medical history, medications, family history, a physical examination, and if necessary, diagnostic testing.

PAIN HISTORY

A pain assessment begins with the history of the problem and can be obtained from written documents and from interviews with the person in pain as well as family members and other caregivers. Pain is a subjective symptom, and pain assessment is, therefore, based on the patient’s own perception of pain and its severity.

Because pain is subjective, a self-report is considered the gold standard, or the best, most accurate measure of a person’s pain. One method to obtain a complete pain history is the PQRST assessment (see box).

PQRST PAIN ASSESSMENT

Provocation/Palliation (P)

- What were you doing when the pain started?

- What caused the pain?

- What seems to trigger it (e.g., stress, position, certain activities)?

- What relieves it (e.g., medications, massage, heat/cold, changing position, being active, resting)?

- What aggravates it (e.g., movement, bending, lying down, walking, standing)?

Quality/Quantity (Q)

- What does the pain feel like (e.g., sharp, dull, stabbing, burning, crushing, throbbing, nauseating, shooting, twisting, stretching)?

Region/Radiation (R)

- Where is the pain located?

- Does the pain radiate, and if so, where?

- Does the pain feel like it travels/moves around?

- Did it start somewhere else and is now localized to another spot?

- Is it accompanied by other signs and symptoms?

Severity Scale (S)

- How severe is the pain on a scale of 0–10, with 0 as no pain and 10 as the worst pain ever?

- Does the pain interfere with activities?

- How bad is the pain at its worst?

- Does it force you to sit down, lie down, slow down?

- How long does an episode last?

Timing (T)

- When or at what time did the pain begin?

- How long did it last?

- How often does it occur (e.g., hourly, daily, weekly, monthly)?

- Is the pain sudden or gradual in onset?

- When do you usually experience it (e.g., daytime, night, early morning)?

- Are you ever awakened by it?

- Does it ever occur before, during, or after meals?

- Does it occur seasonally?

(Crozer Health, 2022)

BEHAVIORAL OBSERVATIONS

Most people who are experiencing pain usually show it either by verbal complaint or nonverbal behaviors or indicators. It is important, however, to remember that people in pain may or may not display behaviors that are considered an indication of “being in pain,” and making judgments about their honesty is inappropriate. Nonverbal indicators of pain may include:

- Restlessness or pacing

- Groaning or moaning

- Crying

- Gasping or grunting

- Nausea or vomiting

- Diaphoresis

- Clenching of the teeth and facial expressions

- Tachycardia or blood pressure changes

- Panting or increased respiratory rate

- Clutching or protecting a part of the body

- Unable to speak or open eyes

- Decreased interest in activities, social gatherings, or old routines

(Toney-Butler, 2023)

TYPES OF PAIN

- Acute: Pain that has lasted for less than a month; usually starts suddenly and has a known cause, like an injury, trauma, surgery, or infection; normally lessens as the body heals

- Subacute: Pain that lasts at least one month but not more than three months; includes conditions such as low back pain, neck pain, broken bones, muscle sprains or strains, dental pain from infection or tooth extraction, pain due to kidney stones, acute episodic migraines, and pain after surgery

- Chronic: Pain that lasts more than three months; can be caused by a disease or condition, injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or unknown reasons; can result from acute or subacute pain that is not effectively managed

(CDC, 2024b)

RISK ASSESSMENT

When clinicians assess patients with chronic pain, it is important to recognize two categories of risk due to opioid therapy: medical conditions that increase their risk for adverse events (e.g., respiratory depression) and risk of misuse, abuse, or addiction.

Risk of Adverse Events

Risk due to medical conditions are assessed and documented as part of the patient’s history and physical examination and the treatment plan adjusted accordingly to reduce risk of adverse events with opioid therapy. Older adults may be at higher risk because of cognitive decline and increased potential for falls. Patients with impaired renal or hepatic function, cardiopulmonary disease, mental health conditions, obesity, and sleep apnea are also at higher risk for adverse consequences when prescribed opioid medications.

Risk for Misuse, Abuse, and Addiction

Variables that have been associated with a higher risk for misuse, abuse, and addiction include history of addiction in biological parents, current drug addiction in the family, regular contact with high-risk groups or activities, and personal history of illicit drug use or alcohol addiction. (See also “Recognizing Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviors” later in this course.)

The use of screening tools is recommended, and multiple tools are available that can help healthcare providers to assess these risks. Examples of screening tools to assess opioid risk or misuse include:

- Opioid Risk Tool: Administered at initial visit prior to beginning opioid therapy; questions address age, family, and personal history of substance abuse, history of preadolescent sexual abuse, and psychological diseases (see below)

- Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI): A series of questions regarding frequency-of-use in adolescent patients of substances most commonly used

- Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription medication, and other Substance use (TAPS): A combined screening and brief assessment that addresses use-related behaviors and generates a risk level for each substance class

- Brief Intervention tool: A 26 item “yes–no” questionnaire to identify signs of opioid addiction or abuse

- CAGE, CAGE-AID, and CAGE-Opioid: CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye-opener) questionnaires consisting of four questions to assess for alcohol abuse and substance abuse (AID and Opioid versions)

- Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM): A 17-item patient self-report assessment designed to identify abuse in chronic pain patients in terms of aberrant behaviors associated with misuse, especially in patients who are already receiving long-term opioid therapy

- Diagnosis, Intractability, Risk and Efficacy (DIRE) tool: A clinician-rated questionnaire to predict patient compliance with long-term opioid therapy

- Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain—Revised (SOAPP-R): A screening questionnaire addressing history of alcohol or substance abuse, cravings, mood disorders, and stress

- Urine Drug Test (UDT): Can be used to evaluate for the use of the medication prescribed and in detecting any unsanctioned drug use

- Rapid Opioid Dependence Screen (RODS): An eight-item screening tool for opioid dependence; can be administered as a stand-alone instrument or as part of a comprehensive interview

- OWLS: A four-item self-administered screening tool to detect prescription OUD in persons prescribed long-term opioid therapy

(Dydyk, 2023; Strain, 2024)

(See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

Treatment Plans

Responsible opioid prescribing requires clinicians to develop treatment plans that focus on patient-centered outcomes and functional goals that improve quality of life. A function-based treatment strategy that aims to maximize the patient’s quality of life and minimize the burden of their pain includes a mutual understanding between prescriber and patient covering the following principles:

- Complete elimination of all pain is often not possible.

- The goal of treatment is to successfully manage pain and not exclusively to reduce a pain scale score.

- Functional goals will be collaboratively set, with the aim of improving quality of life; these goals must be realistic, achievable, verifiable, and meaningful.

- Risks, benefits, side effects, and potential adverse consequences of opioid use will be fully disclosed.

- Education about safe use, storage, and disposal of opioid medication will be provided.

The treatment plan must be documented and include informed consent and patient education.

SAMPLE PATIENT AGREEMENT FORM FOR LONG-TERM CONTROLLED SUBSTANCE PRESCRIPTIONS

Patient Name: __________________

Medication(s): __________________

The use of this medication(s) may cause addiction and is only one part of the treatment for (insert name of condition): __________________

The goals of this medicine are:

- To improve my ability to work and function at home

- To help my condition (e.g., pain, anxiety, etc.) as much as possible without causing dangerous side effects

I have been told that:

- If I drink alcohol or use street drugs, I may not be able to think clearly and I could become sleepy and risk personal injury.

- I may get addicted to this medicine.

- If I or anyone in my family has a history of drug or alcohol problems, there is a higher chance of addiction.

- If I need to stop this medicine, I must do it slowly or I may get very sick.

I agree to the following:

- I am responsible for my medicines. I will not share, sell, or trade my medicine. I will not take anyone else’s medicine.

- I will not increase my medicine until I speak with my doctor or nurse.

- My medicine may not be replaced if it is lost, stolen, or used up sooner than prescribed.

- I will keep all appointments set up by my primary care provider (e.g., primary care, physical therapy, mental health, substance abuse treatment, pain management).

- I will bring the pill bottles with any remaining pills of this medicine to each clinic visit.

- I agree to give a blood or urine sample, if asked, to test for drug use.

Refills:

- Refills will be made only during regular office hours. No refills on nights, holidays, or weekends.

- I must call at least three (3) working days ahead to ask for a refill of my medicine. No exceptions will be made.

- I must keep track of my medications. No early or emergency refills may be made.

Pharmacy:

- I will only use one pharmacy to get my medicine.

- The name of my pharmacy is: _____________________.

- My primary care provider may talk with the pharmacist about my medicines.

Prescriptions from other doctors: If I see another healthcare provider who prescribes a controlled substance for me (e.g., dentist, emergency room doctor, provider at another hospital, etc.), I must bring this medicine to my primary care provider in the original bottle, even if there are no pills left.

Privacy: While I am taking this medicine, my primary care provider may need to contact other healthcare providers or family members to get information about my care and/or use of this medicine. I will be asked to sign a release at that time.

Termination of Agreement: If I break any of the rules or if my primary care provider decides that this medicine is hurting me more than helping me, this medicine may be stopped by my primary care provider in a safe way.

Patient signature: _________________________

Date: _______________________

(NIDA, n.d.)

Periodic Monitoring

It is critical to regularly reevaluate the appropriateness of continuing opioid therapy due to changes in pain etiology, health condition, progress toward functional goals, and addiction risk. To corroborate self-reports, review of data within the prescription drug monitoring program should be conducted at each visit (see “Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs” later in this course). Periodic monitoring should also include urine tests and pill counts when appropriate.

Clinicians must utilize screening and monitoring for all patients on chronic opioid therapy to document patient outcomes and progress toward functional goals. The Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT) is a practical tool that clinicians can use at each patient visit and incorporate into electronic records (see “Resources” at the end of this course). It offers a simple checklist to monitor the “Five As” of pain management (Dydyk, 2023).

| Analgesia | A reduction in pain |

| Activities of daily living | Improvement in level of function |

| Affect | Changes in mood |

| Adverse effects | Falls, decreased cognitive function, constipation, etc. |

| ADRBs | Aberrant drug-related behaviors |

Periodic monitoring timing will vary with each patient. CDC guidelines recommend monitoring every three months at the minimum and before refilling an opioid prescription at any time (Dowell et al., 2022). State requirements may vary.

CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain

In 2022, the CDC updated its guidelines for prescribing opioids for the treatment of pain. The guidelines address four main issues, including:

- Making a determination about whether or not to initiate opioids for pain

- Selecting the appropriate opioid and determining the dosage

- Deciding the duration of the initial opioid prescription and conducting follow-up

- Assessing the risk and addressing the potential harms of opioid use with the patient

These recommendations aim to improve communication between clinicians and patients about the risks and effectiveness of pain treatment; improve pain, function, and quality of life for persons with pain; and reduce the risks associated with opioid pain treatment (including opioid use disorder, overdose, and death) as well as with other pain treatment.

The practice guidelines include 12 recommendations for clinicians who are prescribing opioids for outpatients ages 18 years and older with pain that is acute (duration of <1 month), subacute (duration of 1–3 months), or chronic (duration of >3 months), excluding pain management related to sickle cell disease, cancer-related pain treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care.

- Nonopioid therapies are at least as effective as opioids for many common types of pain. Maximize the use of nonpharmacologic and nonopioid pharmacologic therapies appropriate for the condition and the patient, and only consider opioid therapy for acute pain if benefits are expected to outweigh risks to the patient. Discuss benefits and risks with the patient prior to prescribing opioid therapy.

- Nonopioid therapies are preferred for subacute and chronic pain. Maximize use of nonpharmacologic and nonopioid pharmacologic therapies as appropriate for the specific condition and patient. Consider opioid therapy if expected benefits are anticipated to outweigh risks, and work with the patient to establish treatment goals for pain and function. Consider how opioid therapy will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh risks.

- When starting opioid therapy for acute, subacute, or chronic pain, prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) opioids.

- When opioids are initiated for opioid-naive patients with acute, subacute, or chronic pain, prescribe the lowest effective dosage. If opioids are continued for subacute or chronic pain, prescribe the lowest effective dosage. Avoid increasing dosage above levels likely to yield diminishing returns in benefits relative to risks.

- For those patients already receiving opioid therapy, carefully weigh benefits and risks and exercise care when changing opioid dosages. Work closely with patients to optimize nonopioid therapies while continuing opioid therapy. If benefits do not outweigh risk of continued opioid therapy, optimize other therapies and work closely with patients to gradually taper to lower dosages, or appropriately taper and discontinue opioids. Unless there are indications of a life-threatening issue such as warning signs of impending overdose (e.g., confusion, sedation, slurred speech), opioid therapy should not be discontinued abruptly, and clinicians should not rapidly reduce opioid dosages from higher dosages.

- When opioids are needed for acute pain, prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids.

- Evaluate benefits and risks with patients within 1–4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for subacute or chronic pain or of dosage escalation. Regularly re-evaluate benefits and risks of continued opioid therapy with patients.

- Before starting and periodically during continuation of opioid therapy, evaluate risks for opioid-related harms and discuss risks with patients. Work with patients to incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including offering naloxone.

- When prescribing initial opioid therapy for acute, subacute, or chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring program data to determine whether the patient is receiving opioid dosages or combinations that put the patient at high risk for overdose.

- When prescribing opioids for subacute or chronic pain, consider the benefits and risks of toxicology testing to assess for prescribed medications as well as other prescribed and nonprescribed controlled substances.

- Use particular caution when prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines concurrently and consider whether benefits outweigh risks of concurrent prescribing of opioids and other central nervous system depressants.

- Offer or arrange treatment with evidence-based medications for patients with opioid use disorder. Detoxification on its own, without medications for opioid use disorder, is not recommended because of increased risks for resuming drug use, overdose, and overdose death.

(Dowell et al., 2022)

HOW TO CALCULATE MORPHINE MILLIGRAM EQUIVALENTS PER DAY (MME/DAY)

- Calculate the total daily amount of opioid the patient is prescribed.

- Convert each opioid to MMEs by multiplying the daily dosage for each opioid by its specific conversion factor (see table).

- Add all opioid MMEs together to obtain the patient’s MME.

| Opioid (doses in mg/day except where noted) |

Conversion Factor* |

|---|---|

| * Multiply the dose for each opioid by the conversion factor to determine the dose in MMEs. Dose conversions are estimated and cannot account for all individual differences in genetics and pharmacokinetics. (Dowell et al., 2022) |

|

| Codeine | 0.15 |

| Fentanyl transdermal (mcg/hr) | 2.4 |

| Hydrocodone | 1.0 |

| Hydromorphone | 5.0 |

| Methadone | 4.7 |

| Morphine | 1.0 |

| Oxycodone | 1.5 |

| Oxymorphone | 3.0 |

Example:

A patient with chronic back pain for more than three years is currently taking oxycodone 30 mg twice daily (BID). Calculate the MME.

- Calculate the total daily amount the patient is prescribed.

30 mg × 2 times daily (BID) = 60 mg/day - Multiply the total daily amount by the conversion factor for oxycodone.

60 mg/day × 1.5 = 90 MME per day

TAPERING OPIOID MEDICATIONS

An opioid-tapering flowchart is available from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) that is useful in making determinations about ongoing opioid use or cessation. Tapering is recommended when:

- Pain improves

- The patient requests dosage reduction or discontinuation

- Pain and function are not meaningfully improved

- The patient is receiving higher opioid doses without evidence of benefit from the higher dose

- The patient has current evidence of opioid misuse

- The patient experiences side effects that diminish quality of life or impair function

- The patient experiences an overdose or other serious event (e.g., hospitalization, injury) or has warning signs for an impending event such as confusion, sedation, or slurred speech

- The patient is receiving medications (e.g., benzodiazepines) or has medical conditions (e.g., lung disease, sleep apnea, liver disease, kidney disease, fall risk, advanced age) that increase risk for adverse outcomes

- The patient has been treated with opioids for a prolonged period (e.g., years), and current benefit–harm balance is unclear

(U.S. DHHS, 2019)

PREVENTING PRESCRIPTION DRUG MISUSE

Various actions by healthcare providers can help prevent prescription drug misuse and diversion. These include:

- Educating patients on safe use, storage, and disposal of medications

- Understanding which drugs are commonly misused or diverted

- Recognizing aberrant drug-related behaviors (ADRB) (behaviors that may be associated with misuse of prescription opioids)

- Detecting and responding to drug diversion by patients

Institutional measures are also an important part of addressing the opioid epidemic, such as:

- Medication formulation and abuse-deterrent formulations

- Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs)

- Surveillance systems

Teaching Safe Use, Storage, and Disposal of Prescription Medications

Educating patients on safe use, storage, and disposal of medications is an essential part of addressing the opioid and drug diversion epidemic. Nurses and prescribers can address the following points with patients who have been prescribed opioids.

SAFE USE

- Since opioids come in different forms, understand what type you were prescribed and read the information that comes with your prescription.

- Only take opioids prescribed to you and as directed by your healthcare provider; never take opioids that were not prescribed to you.

- Before you are prescribed opioids, tell your healthcare provider about all other medications and supplements you are taking.

- Do not drink alcohol while you are taking opioids.

- Do not take opioids with medicines that make you sleepy unless your healthcare provider tells you to. Examples include diazepam (Valium), alprazolam (Xanax), abapentin (Neurontin), pregabalin (Lyrica), baclofen, cyclobenzaprine, zolpidem (Ambien).

- Talk to your healthcare provider about your risk for overdose. Tell your healthcare provider if you or your family has a history of alcohol or drug addiction.

- Don’t share your medications with others because they may cause harm to someone else.

- Tell your healthcare provider if you experience changes in your mood, balance, sleep, or pain level and if you find it difficult to stop or decrease opioid use.

- Talk to your healthcare provider about whether it is safe to drive.

- Discuss with your healthcare provider alternative ways to manage your pain.

(AAFP, 2023; UpToDate, 2025)

SAFE STORAGE

Opioids are controlled substances, and their possession and use is regulated by state and federal laws. More than 70% of people who misuse prescription opioids obtain them from family and friends. Therefore, it is important that patients safely store their prescription medications. The CDC also recommends that prescribers discuss risks to household members and other individuals if opioids are intentionally or unintentionally shared with others for whom they are not prescribed, including the possibility that others might experience overdose at the same or at lower dosage than prescribed for the patient.

- Store opioids in their original packaging inside a locked cabinet, a lockbox, or other secure location.

- Do not store opioids in obvious places like bathroom cabinets or on kitchen counters where others might find them.

- Note when and how much medication you take in order to keep track of the amount left.

(AAFP, 2023)

SAFE MEDICATION DISPOSAL

Prescribers and pharmacists often provide specific disposal instructions for unused or expired medicines, and patients are educated to follow those instructions. There are a variety of ways to dispose of medications. The U.S. Food and Drug Administation (U.S. FDA, 2024a) outlines three options for drug disposal according to the type of drug: a take-back site, the flush list, or household trash.

Take-Back Programs

The best way to dispose of most types of unused or expired medicines (both prescription and over the counter) is to immediately drop off the medicine at a drug take-back site, location, or program. Pharmacies, firehouses, or police departments will often “take back” unused medications, particularly opioids. Some areas have specific dates on which they offer this service; other sites will take back medications at any time. Alternately, unused medicines can be sent using a prepaid drug mail-back envelope.

The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) website provides a locator app where the user can search for drug drop-off points within a 10- to 100-mile radius, and each year the DEA sponsors a National Prescription Take-Back Day.

(See “Resources” at the end of this course to locate a disposal location.)

Flushing Disposal

If a drug take-back option or DEA-authorized collector is not available and a medication is on the FDA flush list (see table below), the FDA recommends safely flushing such approved medications down the toilet. The medicines on the flush list are those sought after for their misuse and abuse potential or those that can result in death from one dose if inappropriately taken. For these reasons, FDA recommends that patients flush them down the toilet to immediately and permanently remove these risks from their home.

Based on the available data, the FDA believes that the known risk of harm, including toxicity and death, to humans from accidental exposure to medicines on the flush list far outweighs any potential risk to human health and the environment from flushing these unused or expired medicines (U.S. FDA, 2024b; AAFP, 2023).

| Drug Name | Examples |

|---|---|

| Drugs That Contain Opioids | |

| (U.S. FDA, 2024b) | |

| Any drug that contains the word buprenorphine | Belbuca, Buavail, Butrans, Suboxone, Subutex, Zubsolv |

| Any drug that contains the word fentanyl | Abstral, Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora, Onsolis |

| Any drug that contains the words hydrocodone or benzhydrocodone | Apadaz, Hysingla ER, Norco, Reprexain, Vicodin, Vicodin ES, Vicodin HP, Vicoprofen, Zohydro ER |

| Any drug that contains the word hydromorphone | Exalgo |

| Any drug that contains the word meperidine | Demerol |

| Any drug that contains the word methadone | Dolophine, Methadose |

| Any drug that contains the word morphine | Arymo Er, Avinza, Embeda, Kadian, Morphabond ER, MS Contin, Oramorph SR |

| Any drug that contains the word oxycodone | Codoxy, Combunox, Oxadydo (formerly Oxecta), Oxycet, Oxycontin, Percocet, Percodan, Roxicet, Roxicodone, Roxilox, Roxybond, Targiniq ER, Troxyca ER, Tylox, Xartemis XR, Xtampza ER |

| Any drug that contains the word oxymorphone | Opana, Opana ER |

| Any drug that contains the word tapentadol | Nucynta, Nucynta ER |

| Drugs That Do Not Contain Opioids | |

| Any drug that contains the term sodium oxybate or sodium oxybates | Xyrem, Xywav |

| Diazepam rectal gel | Diastat, Diastat Acudial |

| Methylphenidate transdermal system | Daytrana |

Household Trash Disposal

If a drug take-back program is not available and a medication is not on the flush list, the FDA provides the following guidance on how to dispose of drugs via household trash:

- Remove the drugs from their original containers.

- Mix medicines (liquid or pills; do not crush tablets or capsules) with an unappealing substance such as dirt, cat litter, or used coffee grounds.

- Place the mixture in a container such as a sealed plastic bag.

- Throw away the container in the trash at home.

- Scratch out all personal information on the prescription label of empty medicine bottles or medicine packaging, then trash or recycle the empty bottle or packaging.

Even after fentanyl patches have been used, some medication remains. The FDA recommends promptly disposing of used patches by folding them in half with the sticky sides together and then flushing them down a toilet. Patches should not be placed in the household trash, where children or pets can find them.

Since inhalers are dangerous if punctured or if they come in contact with fire, they must be treated with care. Local trash and recycling facilities typically provide information on how to properly dispose of inhalers in their area (U.S. FDA, 2024a).

Understanding Commonly Abused/Misused Drugs

The Controlled Substances Act regulates five classes of drugs: narcotics/opioids, depressants, hallucinogens, stimulants, and anabolic steroids. All controlled substances have abuse potential or are immediate precursors to substances with abuse potential. The nonsanctioned use of these substances is considered drug misuse. The extent to which the drug is reliably capable of producing intensely pleasurable feelings (euphoria) increases the likelihood of that substance being abused (U.S. DEA, 2024b).

Three specific classes are most commonly abused and thus most susceptible to diversion for nonmedical use:

- Pain medications/narcotics. Opioid pain relievers (narcotics) are the most commonly diverted controlled prescription drugs. Opioid medications are effective for the treatment of pain and have been used appropriately to manage pain for millions of people; however, increased rates of abuse and overdose deaths have raised concerns about proper use of these medications in the treatment of chronic pain. Fentanyl is a potent synthetic opioid drug approved by the FDA for use as an analgesic and anesthetic; it is approximately 100 times more potent than morphine and 50 times more potent than heroin. Overdoses of narcotics are not uncommon and can be fatal.

- Central nervous system (CNS) depressants/sedatives/hypnotics. CNS depressants slow brain activity and are useful for treating anxiety and sleep disorders. Since many patients with pain also experience anxiety or sleep disturbances, increased prescribing of sedative hypnotics has paralleled the increase in prescribing of opioids. Clinicians who add sedative hypnotics to the treatment plan for chronic pain patients may potentiate the risk for patients who are also prescribed opioid medication. In 2023, 3.9 million people misused a prescribed CNS stimulant in the past year, down from 4.3 million in 2022 (SAMHSA, 2024).

- Stimulants. Stimulants are prescribed primarily for treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and narcolepsy. They may also be used as an adjunct medication in the treatment of depression. When taken nonmedically, stimulants can induce a feeling of euphoria and thus have a high potential for abuse and diversion. They also have a cognitive enhancement effect that has contributed to non-medical use by professionals, athletes, and other individuals who rely on productivity. Nonmedical use of stimulants poses serious health consequences, including addiction, cardiovascular events, and psychosis.

(NIDA, 2023; U.S. DEA, 2024b)

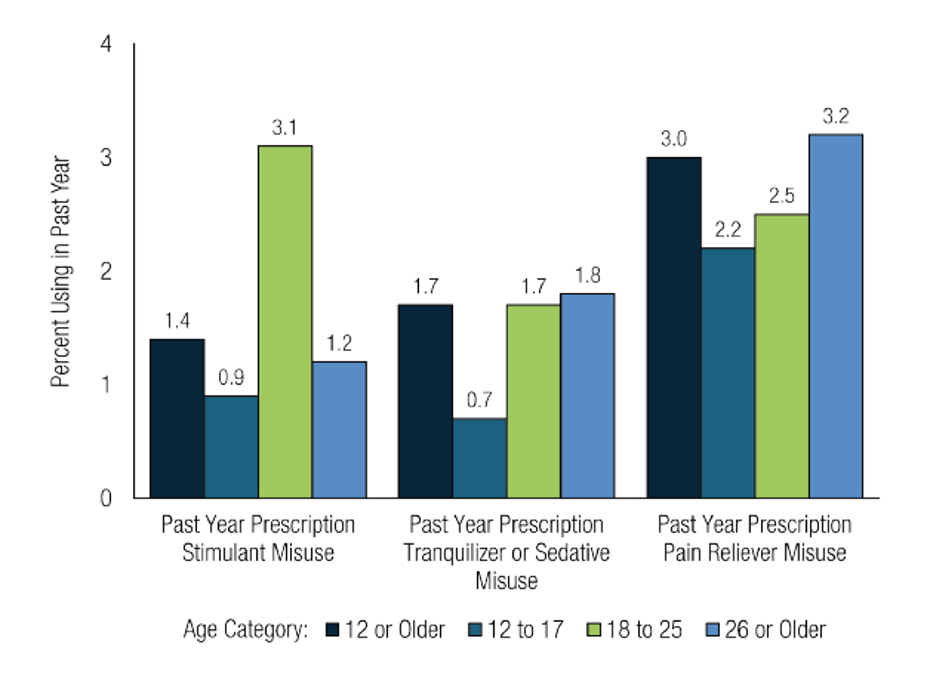

Past-year prescription stimulant misuse, past-year prescription tranquilizer or sedative misuse, or past-year prescription pain reliever misuse among people ages 12 or older, 2023. (Source: SAMHSA, 2024.)

SOURCES FOR MISUSED PAIN RELIEVERS, 2023

- 46.5%, prescription(s) from one or more providers

- 39.1%, free, bought, or taken from a friend/relative

- 8.0%, bought from drug dealer/stranger

- 0.5%, stole from doctor’s office, clinic, hospital, pharmacy

- 5.8%, some other way

(SAMHSA, 2024)

COUNTERFEIT PILLS

Criminal drug networks are mass-producing counterfeit pills and falsely marketing them as legitimate prescription pills. These counterfeit pills are easy to purchase, widely available, often contain fentanyl or methamphetamine, and can be deadly. They are easily accessible and often sold on social media and e-commerce platforms. Many are made to look like prescription opioids such as oxycodone (Oxycontin, Percocet), hydrocodone (Vicodin), and alprazolam (Xanax) or stimulants like amphetamines (Adderall).

Counterfeit pills have been seized in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. In 2024, DEA seized 5.36 million fentanyl pills and over 7,500 pounds of fentanyl powder, equivalent to more than 354 million doses. Five out of 10 pills tested in 2024 contained a potentially deadly dose of fentanyl, down from 7 out of 10 pills in 2023.

The DEA warns that the only safe medications are those obtained from licensed and accredited medical professionals and that pills purchased anywhere other than a licensed pharmacy are dangerous and potentially lethal.

Left: Authentic oxycodone M30 tablet. Right: Counterfeit oxycodone M30 tablet containing fentanyl. (Source: U.S. DEA.)

Recognizing Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviors

Some patients who are prescribed opioid pain medication are at increased risk for opioid misuse and diversion. These patients may demonstrate certain misuse behaviors that can provide clues to the clinician. By recognizing what are called aberrant drug-related behaviors (ADRBs), nurses can respond appropriately and help patients to remain safe.

ADRBs may occur because a patient is experiencing poor pain control or has a fear of uncontrolled pain, which can lead to hoarding of medication. The behaviors may also be attributed to elective use of opioid medication for the euphoric effect or for non-pain-related symptoms such as anxiety, depression, insomnia, and stress.

ADRBs in patients who are prescribed opioids should trigger clinicians to the possibility of addiction. Current literature suggests a range of aberrant drug-related behaviors, with some more predictive of addiction than others. Being aware of the behaviors described in the following box can help guide clinicians who are treating and monitoring patients who are receiving prescription opioid therapy for long-term pain management.

EXAMPLES OF ADRBs

- Altering the mode of administration of drug delivery

- Obtaining prescriptions from nonmedical sources

- Obtaining drugs from other prescribers without informing the clinician

- Stealing or borrowing drugs from others

- Concurrent drug/alcohol use

- Intoxicated/somnolent/sedated

- Occasional impairment

- Pattern of drug-related deterioration

- Medication misuse

- Overdose

- Repeated dose escalations even when warned

- Occasional unsanctioned dose escalation

- Unapproved use of the drug to treat other symptoms

- Unapproved use of drugs to treat nonpainful symptoms

- Repeated resistance to change despite adverse effects

- Noncompliance with therapeutic recommendations

- Increasing pain complaints

- Aggressive complaints about need for more or stronger medication

- Selling prescription drugs

- Prescription forgery

- Frequently lost prescriptions

- Inconsistent urine toxicology screen

- Unkempt appearance without other signs of impairment

- Request for early refills

- Request for specific drugs

- Request for refills instead of appointments with clinician

- Emergency department visits for pain medications

- Saving unused drugs for later use

- Canceled clinic visit

- Discharged from practice

- No show or no follow-up

(Maumus et al., 2020)

The presence of aberrant behaviors, however, may indicate a range of problems other than misuse or diversion, and the clinician must explore a differential diagnosis. Possible etiologies include addiction, pseudo-addiction, another psychiatric disorder, personality disorder, chronic boredom, mild encephalopathy, withdrawal states, and genuine undertreatment of pain. Therefore, it is important to monitor, document, and communicate any aberrant behaviors using objective means and in a team-based fashion over the patient’s entire course of care. This process will also remove any bias on the part of a single provider.

In the hospital setting, monitoring and responding to ADRBs is important in order to:

- Determine the success or failure of treatment

- Help prevent the transition of chronic pain to opioid dependence and SUD

- Help prevent psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression

- Identify undiagnosed SUD

- Identify patients at high risk for diversion

- Identify possible complications of opioid therapy

(Maumus et al., 2020)

RECOGNIZING DRUG SEEKING OR POTENTIAL DRUG DIVERSION BY PATIENTS

- Demands immediate attention

- Recites textbook symptoms

- Gives very vague medical history

- Exaggerates medical condition

- Wants appointments toward the end of office hours or arrives after regular business hours

- Not interested in an examination or undergoing diagnostic tests

- Unwilling to give permission to obtain past medical records

- Claims they failed to pack medication, lost it, or that it was stolen

- Claims that hospital or clinic with past medical records is out of business or burned down

- Deceives providers

- Seeks alternate providers while regular provider is out of the office

- Solicits Medicaid recipients to use Medicaid cards as payment method

- Offers to buy other patient’s pills

- Alters prescriptions

- Falsifies records

- Inflicts wounds to self, family members, and pets

- Requests specific medication due to allergies

- States they are vacationing in area, no local address

- Requests pain medications for a pet

(U.S. DEA, n.d.-a)

System Measures to Prevent Prescription Drug Misuse

System measures are also an important part of addressing the opioid epidemic. Several such measures are discussed below.

MEDICATION FORMULATION

Abuse-deterrent formulations (ADFs) have been developed to help reduce or prevent altered routes of administration—particularly chewing, crushing then smoking, or intravenous injection—used by individuals who misuse opioids. However, questions remain regarding whether prescribing ADF opioids reduces overall opioid misuse. ADFs do not prevent people from taking more than prescribed or change the drugs’ addictive properties.

Abuse-deterrent strategies currently being used include:

- Physical/chemical barriers that prevent chewing, crushing, cutting, grinding, or dissolving, or render it difficult to inhale or inject

- Agonist/antagonist combinations that cause an antagonist (which will counteract the effect of the drug) to be released if the product is manipulated

- Aversive substances that are added to create unpleasant sensations if the drug is taken in a way other than directed

- Delivery systems such as long-acting injections or implants that slowly release the drug over time

- New molecular entities or prodrugs that attach a chemical extension to a drug that renders it inactive unless taken orally

(Rosenquist, 2025)

| Compound | ADF mechanism |

|---|---|

| (Rosenquist, 2025) | |

| Oxycontin (oxycodone extended-release) and abuse-deterrent generic equivalent | Difficult to crush; if dissolved, the tablet forms a viscous gel that is difficult to inject IV. |

| Xtampza ER (oxycodone extended-release) | Capsules contain microspheres of oxycodone and inactive ingredients that hinder dosage dumping via intranasal and oral misuse; microspheres cannot be readily dissolved and will solidify within a needle to prevent injection. |

| Targin (oxycodone extended-release plus naloxone) | Contains naloxone (opioid antagonist), which is not active when taken orally but blocks opioid associated euphoria when injected or inhaled. |

| Roxybond (oxycodone immediate-release) | Difficult to crush; if dissolved, the tablet forms a viscous gel that is difficult to inject IV. |

| Hysingla ER (hydrocodone extended-release tablet) and abuse-deterrent generic equivalent | Difficult to crush; if dissolved, the tablet forms a viscous gel that is difficult to inject IV. |

“PAIN PUMP”

An implanted intrathecal drug delivery system (IDDS), also known as a pain pump, is a device that is surgically implanted and programmed to deliver small amounts of pain medication directly to the intrathecal space of the spinal cord. By administering the medication directly to this area, much lower dosages (less than 1%) are required to relieve pain, often with fewer medication side effects compared to oral formulations (Sivanesan, 2025a).

PRESCRIPTION DRUG MONITORING PROGRAMS

Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are statewide electronic databases that track controlled substance prescription. They can provide health authorities with timely information about both prescribing and patient behaviors, thereby improving opioid prescribing, informing clinical practice, and protecting patients at risk (CDC, 2024d). All U.S. states, Washington, DC, and U.S. territories have operational PDMPs and share data via the Prescription Monitoring Information Exchange (PMIX) National Architecture (PDMP TTAC, 2025).

Some states have implemented polices that require providers to check a state PDMP prior to prescribing certain controlled substances. When pharmacists dispense controlled substances to patients, they have to enter the prescription into the state PDMP. However, pharmacies submit this data to state PDMPs at varying intervals—ranging from monthly to daily to “real-time,” i.e., under five minutes.

PRESCRIBING AND ADMINISTERING OPIOID ANTAGONISTS (NALOXONE)

The availability of the opioid overdose-reversal drug naloxone has been shown to reduce the rate of these overdose deaths, and laws have been enacted in all U.S. states, to expand access to this life-saving medication.

Prescribing Naloxone

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that blocks opioid receptors. The drug comes in intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal formulations and is FDA-approved for use in an opioid overdose and for the reversal of respiratory depression associated with opioid use. In 2023, the FDA approved over-the-counter (nonprescription) naloxone nasal spray (Narcan) (U.S. FDA, 2023). OTC Narcan is now available without a prescription in all states; Washington, DC; and Puerto Rico.

Naloxone can reverse the effects of an overdose from opioids, including:

- Heroin

- Morphine

- Oxycodone (Oxycontin)

- Methadone

- Fentanyl

- Hydrocodone (Vicodin)

- Codeine

- Hydromorphone

CDC guidelines for prescribing opioids recommend that naloxone be coprescribed to any individual who is prescribed high-dose opioid therapy (≥50 MME per day) or any combination of opioids and benzodiazepines. Recommendations also call for overdose prevention education to both patient and household members (Dowell et al., 2022).

Candidates for naloxone include individuals who are concerned about the risk of an opioid overdose, including people who use prescription or illicit opioids, their family members, friends, caregivers, and concerned members of the public. This includes patients:

- Receiving >50 mg morphine milligram equivalent (MME) of opioid treatment

- With a respiratory condition (e.g., COPD, asthma, sleep apnea)

- Who smoke marijuana, hooka, tobacco, etc.

- Being treated for opioid use disorder (DSM-V)

- With a personal or family history of substance misuse (alcohol or drugs)

- Released after having experienced an opioid overdose

- Taking benzodiazepines, hypnotics, muscle relaxers, or other sedative use

- Being switched between opioids product formulations

- With difficult access to emergency services (e.g., rural)

- With heavy alcohol use

- By voluntary request from patient or caregiver

(SAMHSA, 2023b; WV DHHR, 2025b)

Patient Education Regarding Naloxone Administration

Patient education includes showing patients, their family members, or caregivers how to administer naloxone (see below). The medication can be given by intranasal spray or intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intravenous injection.

Individuals who are provided with an automatic injection device or nasal spray should keep the item available at all times. The medication must be replaced when the expiration date passes and if exposed to temperatures below 39 °F or above 104 °F.

Naloxone is effective if opioids are misused in combination with other sedatives or stimulants. However, it typically is not effective in treating overdoses of benzodiazepines or stimulant overdoses involving cocaine and amphetamines unless they are mixed with opioids, such as fentanyl (CDC, 2024e).

Since naloxone is a temporary treatment and its effects will wear off, medical assistance must be obtained as soon as possible after administering/receiving naloxone. Patients must be educated to immediately call 911 after recognizing a possible overdose and before administering naloxone. Individuals who have overdosed may again experience overdose symptoms once the effects of naloxone have worn off, typically after 30–90 minutes.

SIGNS OF OPIOID OVERDOSE

Recognizing the signs of opioid overdose can save a life. They include:

- Small, constricted “pinpoint pupils”

- Losing consciousness, unresponsiveness

- Slow, gargled breathing or no breathing

- Choking or gurgling sounds

- Limp body

- Cold or clammy skin

- Blue lips or nails

(CDC, 2024f)

Side effects of naloxone may include an allergic reaction from naloxone, such as hives or swelling in the face, lips, or throat, for which medical help should be sought immediately. Use of naloxone also causes symptoms of opioid withdrawal. Opioid withdrawal symptoms include:

- Feeling nervous, restless, or irritable

- Body aches

- Dizziness or weakness

- Diarrhea, stomach pain, or nausea

- Fever, chills, or goose bumps

- Sneezing or runny nose in the absence of a cold

Administering Naloxone

Following are instructions on how to administer naloxone.

Step 1. Identify an opioid overdose: Shout to see if the individual responds and gently shake their shoulder. Rub your knuckles on their upper lip or up and down the front of their rib cage.

Step 2. If the individual is unresponsive, call 911.

- State that the individual’s breathing has stopped and they are unresponsive.

- Provide the exact location of the individual.

- Indicate whether or not naloxone has already been given to the individual and if it helped.

Step 3. Perform rescue breathing.

- Place the individual on their back. Place one hand on their forehead and the other under their chin.

- Tilt their chin up gently to open the airway.

- Check to see if there is anything in their mouth blocking their airway, such as gum, a toothpick, undissolved pills, a syringe cap, a fentanyl patch, etc. If so, remove it.

- Pinch their nose with one hand and keep chin tilted up with the other hand. Create an airtight mouth-to-mouth seal and give two even, regular-sized breaths. Blow enough air into their lungs to make their chest rise. If the chest does not rise, make sure you pinch their nose and tilt their head back with each breath.

- Give one breath every five seconds.

Step 4. Give naloxone.

- Follow the instructions provided with the naloxone medication (see below).

- While getting ready to give naloxone, make sure you are not waiting too long between rescue breaths.

- After giving naloxone, continue rescue breathing with one breath every five seconds until emergency responders arrive.

- If victim is still not responding, additional doses of naloxone can be repeated at 2- to 3-minute intervals.

Step 5. Stay until help arrives: Naloxone can reverse an overdose but can also make someone enter withdrawal. After someone is given naloxone, make sure they do not take any more opioids, because they could go back into overdose after the naloxone wears off. They can also go back into overdose if they took a long-acting opioid. In these situations, repeat doses of naloxone may be needed.

(DDPH, n.d.-d)

ADMINISTRATION INSTRUCTIONS

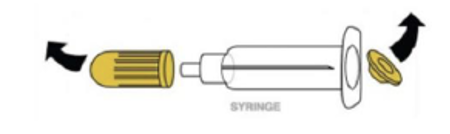

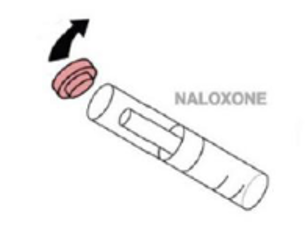

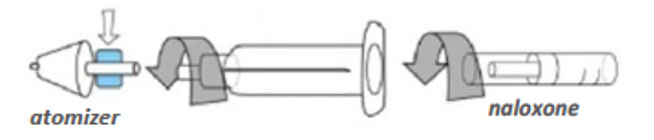

Intranasal Naloxone

- Step 1. Pull or pry off yellow caps.

- Step 2. Pry off red cap.

- Step 3. Grip the syringe.

- Step 4. Gently screw capsule of naloxone into barrel of syringe. Screw white cone (atomizer) onto top of syringe.

- Step 5. Insert white cone into nostril; give a short, vigorous push on end of capsule to spray naloxone into nose, one half of the capsule into each nostril. For best results, aim away from the middle of nose (toward ear).

- Step 6. If not breathing in 3 minutes, give a second dose.

Evzio Injectable Naloxone

- Step 1. Pull Evzio from outer case.

- Step 2. Follow the directions provided through the speaker in the device.

- Step 3. If not breathing in 3 minutes, repeat steps with the other device from the box.

- Note: May be injected through the person’s clothes.

Narcan Nasal Spray

- Step 1: Place nozzle in either nostril until your fingers touch the bottom of the person’s nose.

- Step 2. Point the nozzle toward the person’s ear (away from the middle of the face).

- Step 3. Press the plunger firmly to release the medication.

- Step 4. If the person is not breathing well after 3 minutes, repeat with the other device in the package.

![Narcan nasal spray.]](791/xnarcan-nasal-spray.png.pagespeed.ic.0qKAQ_4H4k.jpg)

(WV DHHR, n.d.)

CHEMICAL DEPENDENCY AND IMPAIRMENT IN THE WORKPLACE

Healthcare professionals may be at increased risk for misuse or diversion of prescription medications due to working in environments where frequent and easy access to controlled substances is part of their daily work routine.

Drug Diversion Among Healthcare Professionals

Drug diversion from the workplace is seen across all clinical disciplines and all levels of an organization, from management to frontline staff. Diversion may occur with opened or unopened vials, partially used doses of medication that are not wasted, and medication that has been disposed of and left in sharps containers. The drugs most commonly diverted from healthcare settings are opioids. While drug diversion is substantially underestimated, undetected, and unreported, an increasing number of drug diversion incidents has accompanied the rise of the opioid epidemic. For instance:

- In 2024, a nurse was sentenced to 12 months in prison for stealing fentanyl and hydromorphone intended for intensive care patients. She admitted to removing the pain medication from their vials, refilling the vials with tap water, and returning the vials to the controlled storage locker.

- In 2023, a nurse pled guilty to diverting controlled substances from her hospital for her own use, including falsely documenting she had administered medications to patients.

(Nyhus, 2021; HealthcareDiversion.org, 2025)

Practitioners, including prescribers, may also be motivated to divert drugs for several reasons:

- Money/financial gain

- Fear

- Stop blackmail

- Sexual favors

- Stay in business/codependency

- Addicted family members

- Personal use/misuse

(U.S. DEA, 2018)

RECOGNIZING WORKPLACE DIVERSION

Every clinician plays an important role in drug diversion prevention and should be able to recognize patterns, trends, and behaviors associated with drug diversion in the workplace. These may include:

- Consistently arriving early, staying late, or frequently volunteering for overtime

- Frequent breaks or trips to bathroom

- Heavy wastage of drugs

- Drugs and syringes in pockets

- Anesthesia record that does not reconcile with drug dispensed and administered to patient

- Patient with unusually significant or uncontrolled pain after anesthesia

- Patients with a higher pain score as compared to other anesthesia providers

- Times of cases that do not correlate with when provider dispenses drug from automated dispenser

- Inappropriate drug choices and doses for patients

- Missing medications or prescription pads

- Drugs, syringes, or needles improperly stored

- Signs of medication tampering, including broken vials returned to pharmacy

- Compromised product containers

- Frequent medication losses, spills, or wasting

- Controlled substances removed without a prescriber’s order

- Controlled substances removed on recently discharged or transferred patient

- Controlled substances removed for a patient not assigned to the nurse

- Medication documented as given but not administered to the patient

- Frequent reports of ineffective pain relief from patients

- Frequent unexplained disappearances from the unit

- Incorrect controlled substance counts

- Consistently documenting administration of more controlled substances than other nurses

- Numerous corrections on medication records

- Offers to medicate coworkers’ patients for pain

- Saving extra controlled substances for administration at a later time

- Altered verbal or phone medication orders

- Variations in controlled substance discrepancies among shifts or days of the week

(AANA, n.d.)

QUESTIONS TO IDENTIFY DIVERSION AMONG PRESCRIBERS

While none of the actions described below indicates definitively that a practitioner is engaged in diversion or illegal prescribing, asking the following questions may help identify possible diversion among practitioners:

- Does the practitioner follow state laws when prescribing controlled substances?

- Does the practitioner conduct cursory medical exams or any medical exam at all?

- Does the doctor perform diagnostic testing or refer patients out for diagnostic testing?

- Is the practitioner referring patients to other specialists (surgery, physical therapy, etc.)?

- Are the initial office visits or follow-up visits brief?

- Does the practitioner prescribe multiple drugs within the same drug category?

- Does the practitioner prescribe excessive quantities of controlled substances relative to the medical condition the prescription is purported to treat?

- Do patients travel a great distance to see the practitioner?

- Does the practitioner ignore signs of abuse?

- Patient appears to be under the influence

- Patient asks for the controlled substances they want

- Patient is doctor shopping in PDMP

- Practitioner is warned by family members that the patient is abusing or selling his controlled substances

- Does the practitioner ignore toxicology reports?

- Does the practitioner only treat patients with narcotic controlled substances?

- Does the practitioner start on a low-dose or low-level controlled substance and then over time work up to higher levels, or does the practitioner just start patients on a high-dose narcotic?

- Does the practitioner continue to prescribe controlled substances to patients even though it would be ineffective for treatment purposes?

- Does the practitioner allow the non-medical staff to determine the narcotic to be prescribed, and the practitioner just signs the prescription?

- Does the practitioner coach patients on what to say so that patients can get the narcotics that they want?

- Does the practitioner violate pain management policies and guidelines?

- Does the practitioner ignore warnings from insurance companies, law enforcement, other practitioners, family members, etc.?

- Does the practitioner receive other compensation for narcotic prescriptions (sex, guns, drugs, etc.)?

- Does the doctor still charge patients for visits if the patients do not receive narcotic prescriptions?

- Are patient deaths attributed to drug abuse or overdose?

- Does the practitioner use inventory for personal use?

(U.S. DEA, n.d.-a)

PREVENTING WORKPLACE DIVERSION

A comprehensive strategy to prevent the diversion of controlled substances includes efforts at the points in the medication management process where diversion may occur. Organizational prevention programs include elements across multiple levels:

- Administrative level: following all legal and regulatory requirements, providing organizational oversight and accountability

- System level: human resources management, automated dispensing technology, monitoring and surveillance, and investigation and reporting

- Individual level: chain of custody; storage and security; internal pharmacy controls; prescribing and administration; returns, waste, and disposal

(Clark et al., 2022)

Specific controls shown to be effective against diversion of controlled substances include:

- Following all policies and procedures

- Using the PDMP regularly

- Keeping complete and accurate records

- Limiting access to drug inventory

- Storing controlled substances in a securely locked cabinet

- Not sharing passwords

- Conducting audits to discover discrepancies, losses, or thefts

- Verifying destructions

- Training and updating staff

- Being vigilant of staff members

- Conducting background checks of prospective employees

- Conducting drug testing at hiring and random drug testing thereafter

- Questioning and reporting suspicious activities/transactions

- Using electronic prescriptions to reduce forged/altered/fraudulent scripts

- Never signing prescription blanks in advance

- Keeping prescription pads locked when not in use; not leaving prescription pads unsecured (e.g., in jacket pocket)

- Inspecting and numbering prescription pads

- Clearly indicating/writing the amount prescribed

(U.S. DEA, 2018)

Recognizing Impairment in the Workplace

Impairment from substance use disorder, drug diversion, or other physical or psychological causes has far-reaching impact. It not only threatens the health and safety of patients but also creates serious consequences for the impaired professional, colleagues, and the healthcare facility that employs the impaired clinician.

The Nurse Worklife and Wellness Study found that in the year prior to the study illicit drug use among nurses was 5.7% and misuse of prescription drugs was 9.9% (Trinkoff et al., 2022). The exact number of nurses afflicted is unknown, but the prevalence of addiction among nurses is believed to mirror the general population.

RISK FACTORS FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Healthcare professionals may be at increased risk for abuse of prescription-type medication due to the added risk of working in environments where frequent and easy access to controlled substances is part of their daily work routine. For instance, evidence suggests the types of drugs abused by nurses may depend on what drugs are most accessible in their individual work environments. The most common prescription drugs abused by nurses are benzodiazepines and opioid painkillers such as fentanyl and hydrocodone. Nurses who abuse prescription drugs are those who have the greatest access, with the highest rates of abuse among nurse anesthetists (American Addiction Centers, 2023).

WORKPLACE RISK FACTORS

- High-stress work environment

- Low job satisfaction

- Role strain

- Long hours and irregular shifts

- Fatigue

- Periods of inactivity or boredom

- Remote or irregular supervision

- Easy access to controlled substances

- Lack of education regarding substance use disorders

- Nursing attitudes toward drugs

- Lack of pharmaceutical controls in the workplace

- “Enabling” by peers and managers

(Addictions.com, n.d.; Smith, 2021)

SIGNS OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND IMPAIRED PRACTICE

Impairment renders a clinician unsafe to provide patient care. Physical, psychosocial, and behavioral clues, however, can be subtle and easily overlooked. Colleagues may notice clues but seek other explanations and avoid suggesting substance abuse as a possible cause.

Generally, disruptions in family, personal health, and social life manifest long before an individual shows evidence of impairment at work. Thus, all indicators, no matter how subtle, appearing in the workplace must be taken seriously. Any of the following may be signs of impairment in the workplace, and patterns of such behavior and a combination of these signs are cause for increased suspicion.

| Type | Signs |

|---|---|

| (Nyhus, 2021; AANA, n.d.; Kopitnik & Siela, 2024) | |

| Physical |

|

| Psychosocial |

|

| Behavioral |

|

INTERVENING IN CASES OF IMPAIRED PRACTICE IN A COLLEAGUE

When planning to intervene in a case of suspected impairment, the first step is knowing state laws and rules pertaining to substance abuse and impairment in the workplace among licensed healthcare providers. It is also important to be familiar with and to follow an employer’s policies and procedures relating to substance abuse and impairment.

Healthcare professionals can follow these steps when they begin to notice possible impaired practice in a colleague:

- Observe job performance; be aware of signs and symptoms of impairment that are common in the workplace.

- Look for patterns of behavior indicating possible impairment that are consistent over a period of time.

- Document (date, time, place, witnesses) any inappropriate behavior; be concise and include objective, clear, and factual information:

- What happened?

- Who was involved?

- When did the incident occur?

- How was it discovered?

- Where did it occur?

- Were there any witnesses?

Supervisors should be involved in planning an intervention and taking steps to respond to concerns about impairment in the workplace.

- Planning and participating in an intervention are critical responsibilities of the manager, and it should never be implemented alone.

- It is important to develop a careful plan of action before implementing an intervention and also important to secure help.

- Interventions should focus on documented facts.

- The primary objective of an intervention is to request the clinician refrain from practice until a fitness-to-practice evaluation has been completed (IPN, 2023).

- To assure safety, a clinician who is impaired should never be left alone and should not be permitted to drive.

State practice acts typically require licensed healthcare professionals to report any other similarly licensed professional when they reasonably believe that the practitioner is or may be guilty of unprofessional conduct or unfit to practice. State laws similarly include confidentiality provisions for the person who makes such a report and also provide for immunity from civil or criminal prosecution for good faith reporting. All licensed healthcare professionals must become familiar with the requirements of the applicable practice act and laws in their own jurisdiction.

As an alternative to discipline, some states provide for a voluntary treatment option for licensed professionals determined to have violated the professional conduct standard related to impairment or dependence on alcohol or drugs. They may be permitted to continue to practice, subject to any limitations on practice established by their licensing board and only if the licensed professional presents no danger to public health, welfare, or safety.

RELUCTANCE TO REPORTING

There are many reasons why peers may be reluctant to report their colleagues for impaired practice, including:

- Uncertainty about reporting requirements

- Uncertainty of consequences to their peer, such as loss of license and job

- Concern about retaliation by peer

- Fear of social stigma of reporting a peer

- Reluctance to report if not 100% sure

NONPHARMACOLOGIC INTERVENTIONS FOR PAIN

Evidence-based nonpharmacologic therapies are safe when correctly administered and can be effective components of comprehensive pain management that can reduce the need for opioids. Nonpharmacologic therapies can be the sole intervention, or they can be combined with other treatments. Nonpharmacologic interventions include physical, psychological, and mind–body modalities.

Many disciplines are involved in managing a patient’s pain through the use of these nonpharmacologic approaches. The most important member of the interdisciplinary team is the person with pain—the patient. Other team members may include:

- Significant others (family, friends, etc.)

- Physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners

- Nurses

- Psychologists

- Occupational therapists

- Physical therapists

- Recreational therapists

- Vocational counselors

Physical modalities for relief of pain refer to any therapeutic medium that uses the transmission to or through the patient of thermal, electrical, acoustic, radiant, or mechanical energy.

- Thermal modalities (heat and cold)

- Manual modalities (massage, manipulation therapy)

- Acupuncture

- Electrophysical agents (TENS, iontophoresis, percutaneous electric nerve stimulation)

- Acoustic modalities (ultrasound, phonophoresis, shortwave and microwave diathermy, vibroacoustic therapy)

- Light therapy (low-level laser, ultraviolet light)

- Interventional modalities (injection, radiofrequency ablation, intrathecal pump, spinal cord stimulator)

- Dry needling

(See also “Physical Therapy and Pain Management” below.)

SPINAL CORD STIMULATOR

A spinal cord stimulator is a surgically implanted device used to relieve pain via low-level electrical impulses sent directly into the spinal cord. This modality is typically employed when other pain treatment options have failed to provide sufficient relief. The device consists of electrodes placed in the epidural space and a small generator (battery pack) placed under the skin, usually near the buttocks or abdomen. Spinal cord stimulators allow patients to use a remote control to send electrical impulses when they feel pain. Traditional spinal cord stimulators replace the sensation of pain with paresthesia (light tingling), while newer devices provide “sub-perception” stimulation that cannot be felt (Sivanesan, 2025b).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain (CBT-CP) is a first-line treatment. This evidence-based modality employs cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and lifestyle changes to interrupt neurophysiologic processes that trigger and maintain pain. The goals of treatment are to alter cognitions, emotions, physical sensations, and maladaptive coping behaviors that perpetuate chronic pain, such as:

- Unhealthy thinking patterns

- Negative emotions

- Physical factors such as muscle tension

- Inactivity, isolation, and avoidance

- Lifestyle habits such as sleep, nutrition, and exercise

(UCSF, 2025a)

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a cognitive-behavioral approach that helps patients accept difficult thoughts, feelings, sensations, and internal experiences while increasing their commitment to healthy, constructive activities. It is based on the theory that increasing acceptance can lead to increased psychological flexibility (Glasofer, 2024).

Biofeedback is a technique used for chronic pain conditions. It involves using instruments to train a patient to develop awareness of and control psychophysiologic processes, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and skin temperature. Developing emotional calm can activate the pain suppression system. Applications include muscle pain, including bruxism and TMJ, neck pain, and low back pain; IBS; chronic headache; and pelvic pain.

Common outcomes after biofeedback sessions for pain include:

- Better control over pain intensity and response to pain (anxiety, depression, panic, anger)

- Reduced dependence on opioids and analgesics

- Having something to practice and improve upon (body control of some type)

- Improved quality of control over attention to pain and diminished anxiety and suffering

Biofeedback can be integrated with other mind–body techniques. These include cognitive change, emotional regulation, attention control, meditation and mindfulness, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, regulated breathing, Autogenics (desensitation-relaxation technique), Open Focus (attention training), and yoga (UCSF, 2025b).

Hypnosis has been shown to relieve chronic pain from cancer, burns, and rheumatoid arthritis (Duncan, 2024). Through hypnosis, the patient is guided to an altered state of consciousness in order to focus attention and reduce the discomfort of pain.

Distraction is another proven pain-relieving technique. It involves diverting attention from feelings and thoughts of pain by activities such as watching TV or listening to music (Stanford Health Care, 2025).

Mirror therapy is a rehabilitation therapy in which a mirror is placed between the arms or legs so that the image of a moving, nonaffected limb gives the illusion of normal movement in the affected limb. Mirror therapy exploits the brain’s preference to prioritize visual feedback over somatosensory/proprioceptive feedback concerning limb position. The reflection “tricks” the brain into thinking there are two healthy limbs (Physiopedia, 2022a).

Occupational Therapy and Pain Management

The role of the occupational therapist within an integrative pain management program focuses on function in daily living and takes a holistic and comprehensive approach to evaluate structural, physiologic, psychological, environmental, and personal factors that influence the experience of pain. The information obtained by patient evaluation is then used in the application of self-management strategies, functional activities, hands-on techniques, and specific exercises to improve function and participation.

Depending on the area impacted by chronic pain, the occupational therapist provides the following interventions:

Physical mobility:

- Adaptive equipment selection and training

- Positioning equipment and strategies

- Functional mobility training (e.g., static positioning, dynamic movement, transfers, lifting and bending techniques)

Activities of daily living/self-care:

- Neuromuscular reeducation

- Nerve mobilization

- Functional range of motion and strengthening exercises

- Activity pacing and energy conservation strategies

- Ergonomic and body mechanics training

- Fall prevention and safety

- Home evaluation

Instrumental activities of daily living:

- Adaptive equipment selection and training

- Transportation training, including comprehensive driver evaluations and driver rehabilitation

Health management:

- Patient education and disease self-management training, including trigger identification, symptom tracking, and pain flare-up planning

- Pain coping strategies, including physical modalities, complementary and alternative pain coping strategies, sensory strategies, self-regulation, and mobilization

- Pain and assertive communication training

- Medication management

- Eating routine strategies to avoid dietary pain triggers and improve energy management

- Establishing sustainable physical activities

- Time management strategies

Rest and sleep: