Forensic Evidence Collection for Texas Nurses

Sexual Assault Survivor Examination Guidelines

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

MANDATORY TEXAS NURSING CEU. Fulfills the 2-hour continuing nursing education (CNE) requirement for Texas nurses practicing in an emergency department setting. Course covers assessment, forensic evidence collection procedures, documentation, and providing testimony.

"Thorough and detailed course. I am a better nurse for reviewing this material. The course layout was organized and helpful. Thanks, Wild Iris!" - Pamela, RN in Texas

"Good course to follow and understand for a non-ED nurse needing a required educational course on forensic nursing." - Kathleen, RN in Texas

"Very well-organized explanation of what is expected of ED nurses." - Linday, RN in Texas

"This course was very informative and easy to understand and apply to my practice." - Kathryn, RN in Texas

Forensic Evidence Collection for Texas Nurses

Sexual Assault Examination Guidelines

Copyright © 2023 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will demonstrate an understanding of the forensic sexual assault evidence collection process, including obtaining a history and collecting, preserving, and documenting forensic evidence according to Texas legal standards. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Identify key points of the Texas Evidence Collection Protocol for sexual assault.

- List the types of sexual assault forensic exams.

- Discuss elements of patient-centered care.

- Describe the sexual assault evidence kit (SAEK).

- Outline the steps involved in collecting forensic evidence.

- Explain how best to document and photograph evidence.

- Summarize the means used to preserve the integrity and security of evidence of a sexual assault.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Survivors of sexual assault in Texas have the legal right to a forensic exam if they report the assault within 120 hours. These individuals, therefore, require professional caregivers who are trained to collect evidence in an effective and compassionate manner.

Since there is a national shortage of certified Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE), Texas’s Senate Bill 1191 requires that all nurses who work in the emergency department receive basic education in how to collect forensic evidence of a sexual assault. This basic training for emergency nurses is not the same as the training required for certified Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners.

The ability to collect evidence in every emergency department offers patients the option to be treated locally as opposed to traveling a long distance to a center that is staffed by a certified Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner. The ability for a survivor to be treated locally in the emergency department can also eliminate the need for law enforcement to transport the individual to another location, thereby allowing police officers to remain on duty in their own community (Advocate Editorial Board, 2018).

TEXAS EVIDENCE COLLECTION PROTOCOL

The Texas Evidence Collection Protocol (TECP), updated in 2022, guides healthcare providers who are conducting forensic medical assessments for patients who report sexual assault and addresses the roles of the multidisciplinary team to provide a trauma-informed, patient-centered response. The protocol is an excellent reference and is available online (see “Resources” at the end of this course).

Key Points of the TECP

Following are key points from the protocol:

- Sexual assault is a trauma, regardless of the presence of physical injuries. Healthcare providers can help reduce the neurobiological response to trauma by providing trauma-informed care that restores safety, security, and control to patients.

- Treat emergent medical conditions before, or concurrently to, addressing forensic issues such as evidence collection.

- Nonfatal strangulation is a life-threatening event that requires specialized assessment and close patient monitoring.

- Patients guide the assessment process and have the right to decline any part, or all, of the examination and evidence collection.

- Use open-ended questions that allow patients to provide their narrative of what occurred.

- In all patient interactions, it is important to maintain confidentiality of forensic medical information and documentation. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) applies to this patient population.

- Offering access to a sexual assault advocate during the forensic medical assessment is mandated by Texas law. This advocate is distinct and separate from healthcare, law enforcement, and judicial personnel.

- Mandatory reporting is required for suspected abuse of children, older adults, or a person with a disability, regardless of the wishes of the patients, their families, or friends.

- Two types of patients—children and suspected perpetrators—should always be seen by a forensic expert (sexual assault nurse examiner, forensic nurse examiner, child abuse pediatrician, or specially trained medical forensic professional). Children should also be seen in a child advocacy center.

- Suspected perpetrators should always be seen by a forensic expert and care must be taken to keep suspected perpetrators separated from survivors for psychological and physical safety reasons.

- During the examination and evidence collection process, avoid contamination of potential evidentiary items. After all the evidence and clothing have been collected by the healthcare provider, labeled, and sealed appropriately, evidence should be opened only by crime laboratory personnel.

- All patients should receive person-first, culturally responsive, trauma-informed, quality, and unbiased healthcare.

- It is critical that adult military-affiliated survivors receive information about their reporting options from a person knowledgeable of the Department of Defense policy that defines reporting.

- Policies should be in place regarding the process for obtaining photographs; the method used to identify the patient in the photographs; and documentation that the photographs exist in the permanent medical record for each patient.

- All patients are entitled to a medical forensic examination (Texas Code of Criminal Procedure §56).

- Adult patients who do not meet mandatory reporting criteria may choose to have sexual assault evidence collected without reporting to law enforcement (Texas Health and Safety Code §323).

- A sexual assault evidence collection kit should be used only when indicated, as described in Subchapter F (Texas Code of Criminal Procedure §42).

(Texas A&M, 2022)

Types of Sexual Assault Forensic Exams

The TECP describes the following types of sexual assault forensic exams:

- Adults (18 years and older). Evidence may be collected up to 120 hours after an assault. Adult patients have the option of requesting that evidence be collected with or without law enforcement involvement. The option for an exam without law enforcement involvement is referred to as a nonreport exam.

- Military adults. The military offers a “restricted” nonreporting exam option. Military survivors have legal options that are exclusive to the military system. In order to preserve the patient’s privacy rights within the military justice system, it is best to ask the patient to talk to an advocacy representative from the Department of Justice.

- Adolescents. Adolescents are defined as children under the age of 18 who have reached puberty. Mandatory reporting requirements apply to this group, and an adolescent may consent to the exam without a parent or guardian’s permission. A minor who is at least 16 years of age may decline any part or all of an exam.

- Children (under the age of 18). Exams of these patients should be conducted by a skilled and certified sexual assault examiner. Pediatric exams to collect evidence are done within 120 hours of an event, but another type of exam may be done for children who report abuse beyond 120 hours. Mandatory reporting requirements apply to this group. A child of any age may withhold their assent for a procedure.

- Elders (age 65 and over) and adults with disabilities should be examined by a certified sexual assault examiner. They may consent to an exam without a conservator’s permission (if applicable). Mandatory reporting applies to these groups.

- Suspect exams. Exams of suspected perpetrators of sexual assault should be conducted by someone who has specialized training.

MANDATORY REPORTING REQUIREMENTS

Vulnerable populations include minors (under 18), older adults (over 65), and dependent adults. If patients who belong to these groups report a sexual assault, the nurse must make a mandatory report to the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services or to law enforcement if there is an immediate threat. The reporting of suspected abuse cannot be delegated (Texas Family Code §261.101). (See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

In Texas, any competent adult has the option of reporting or not reporting a sexual assault to law enforcement.

PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

It is important for healthcare practitioners to recognize that sexual assault is a traumatic event and, therefore, to provide patient-centered care. When conducting an exam, obtaining the history, and collecting evidence, a trauma-informed approach is essential because violence and abuse can cause psychological distress. Trauma-informed care restores safety, security, and control to patients.

- Begin the interview by offering the patient the services of an advocate. Texas law requires that the survivor be offered the support of a certified sexual assault advocate. This person has been trained to support the patient through the exam and future involvement with the criminal justice system. Advocates can also assist patients with access to counseling and reimbursement through the criminal justice system for out-of-pocket costs. A survivor also has the legal right to the presence of an additional support person of their choice (e.g., family member, friend) (Texas A&M, 2022).

- Obtain consent. Patients must consent to the evidence collection process. This consent should allow both the collection of evidence and the release of evidence to law enforcement. It is recommended that the consent form also include consent for photographs if they will be taken. Specific statutes address child or nonparental consent as well as consent for adults with cognitive disabilities (see also “Resources” at the end of this course).

- Offer the option of a nonreport exam. Offer adult patients ages 18–64 without a disability the choice to undergo a forensic exam with or without law enforcement involvement. A patient who reports a sexual assault within 120 hours has the right to a forensic examination without making a report to law enforcement. Evidence may be collected and stored, and the patient can decide up to five years later whether or not to have the evidence processed and engage with the criminal justice system.

Survivor Response to Trauma

Individuals respond to trauma in various ways based on their own background, developmental phase, and the type of trauma inflicted. Each survivor’s response to trauma is unique and self-defined. Approximately 30% of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) cases in the United States are attributed to sexual violence. Typically, the physical injuries that survivors sustain during a sexual assault are minor and do not require treatment, but psychological injuries are common and may negatively impact the survivor’s life.

Common symptoms of survivors of sexual assault include:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Flashbacks or hypersensitivity to reminders of the traumatic event

- Intrusive thoughts

- Avoidance of thoughts, people, and places that may trigger memories of the trauma

- Easily triggered emotions

- Negative effect on daily life

It is important for healthcare professionals to address the patient’s mental and physical needs. Persons who have experienced trauma should be made aware of resources to seek help, since early intervention may prevent long-term conditions such as PTSD, chronic pain, depression, chemical dependency, and suicidality (Texas A&M, 2022).

Elements of Trauma-Informed Care

Trauma can impact a patient’s ability to think, remember, and relay the history of the event in chronological order. The clinician therefore considers the vulnerabilities and experiences of the patient as well as acknowledges the impact of the traumatic event. The following practices can improve the patient’s ability to recall information accurately. These methods are based on an understanding of the neurobiology of trauma.

- Build rapport and establish trust with the patient.

- Let everyone know what actions will be taken in advance of the occurrence.

- Acknowledge the patient’s distress.

- Provide an environment that encourages a feeling of safety both physically and emotionally by asking the patient what they need to feel safe.

- Offer choices.

- Use nonleading, open-ended questions that allow for narrative responses.

- Minimize interruptions.

- Focus on what the patient can remember thinking and feeling during the event.

- Begin by asking general health information and explain why the questions are asked.

- Focus on sensory details of the assault, such as colors, smells, sensations, or features of the assailant.

- Maintain patience and express empathy and understanding.

- Expect that information may be relayed out of chronological order.

- Give the patient permission to say “I don’t know” rather than guess.

- Refrain from asking the patient “why” questions and maintain a nonjudgmental attitude.

- Speak slowly and clearly and allow the patient to take breaks as needed.

- Be mindful of the patient’s developmental stage.

(Texas A&M, 2022)

Language and Cultural Awareness

Patients have the right to choose the language and format that information is given to them. It is not appropriate to utilize family or support persons as interpreters. Most facilities have access to interpreters as well as other resources to assist the clinician in ensuring that the patient fully understands and can give informed consent (see “Resources” at the end of this course) (Texas A&M, 2022).

In addition to addressing the patient’s English-language proficiency, the nurse must respond sensitively to patients in matters of race, ethnicity, gender and gender identity, religion, disability, immigration status, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, and developmental stage. Any of these factors may influence how a patient experiences the exam. Each patient is an individual and may have different beliefs from the clinician, which should be respected (Texas A&M, 2022).

It is best practice to ask patients about how they identify their own gender rather than to make assumptions (IAFN, 2020). Patients should be asked their pronouns (e.g., he, her, they, etc.), and the nurse should replace heteronormative language with gender-neutral terms when caring for patients who identify as LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning). As of 2021, the state of Texas has the second highest number of people (1.8 million) who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender in the United States (PPIC, 2022).

SEXUAL ASSAULT EVIDENCE KIT

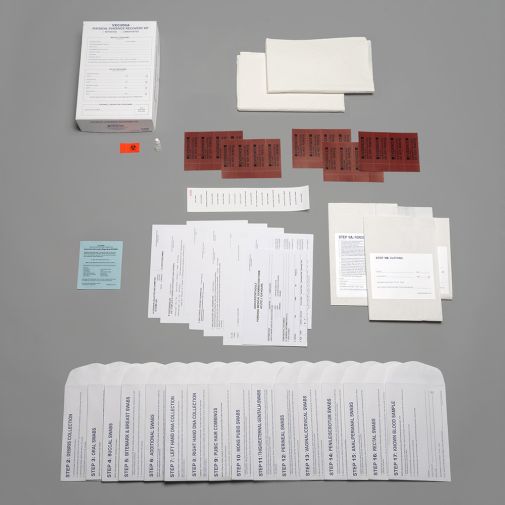

Every emergency department should have a sexual assault evidence collection kit (SAEK) containing most of the equipment needed to collect evidence. Any SAEK should be in a tamper-evident container. The integrity of the kit’s seal should be verified on a routine basis, and the examiner should not use any kit with a broken seal. The Texas Attorney General’s Office approves kits based on Texas evidence requirements. Facilities may also create their own kits.

The SAEK generally contains swabs, swab boxes, a comb, envelopes, clothing collection paper, adhesive seals, and paper bags. Additional supplies that the examiner may need include, but are not limited to, powder-free gloves, sterile water, additional swabs, and a camera. The SAEK contains boxes in which swabs can dry. Documentation forms may be included in the SAEK, downloaded, or provided by the institution (see “Resources” at the end of this course).

Urine and/or blood specimens are collected separately in cases of suspected drug-facilitated sexual assault (Texas A&M, 2022).

Sample sexual assault victim evidence collection kit. (Source: Sirchie. Reprinted by permission.)

SAMPLE SEXUAL ASSAULT VICTIM EVIDENCE COLLECTION KIT CONTENTS

- 1 photo documentation guidelines form

- 1 instructions/FDA form

- 1 Step 1 release form

- 1 Step 2 patient history form

- 1 Step 3A foreign material bag

- 2 Step 3B clothing bags

- 2 Step 3C underwear bags

- 2 drape sheets

- 1 Step 4 debris collection envelope containing paper bindle

- 1 Step 5 dried secretions envelope containing swabs and swab boxes

- 1 Step 6 head hair combings envelope containing paper towel and black comb

- 1 Step 7 external mouth swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 8 oral swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 9 known DNA samples envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 10 fingernail swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 11 hand swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 12 pubic hair combings envelope containing paper towel and comb

- 1 Step 13 penile swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 14 scrotal swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 15 anal/perianal swabs envelope containing swabs and swab box

- 1 Step 16 rectal swabs envelope swabs and swab box

- 1 evidence collection log form

- 1 kiss marker, item

- 1 kiss marker, rings item

- 1 swab box label

- 1 distilled water, 1 oz

- 20 police evidence seals

- 1 biohazard label

(Sirchie, 2023)

FORENSIC MEDICAL ASSESSMENT

When a patient presents to the emergency department and reports being sexually assaulted, medical treatment always takes precedence over evidence collection. All patients are first evaluated for pain, bleeding, and safety. The CDC also recommends baseline testing of patients who may have been sexually assaulted for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancy. Any patient who reports being strangled or who has sustained a head injury should be seen by a physician prior to or while collecting evidence (DOJ, 2013; Texas A&M, 2022).

The forensic medical exam consists of obtaining the history; a physical assessment; and collection of potential biological, physical, or trace evidence. All evidence must be tracked in the statewide sexual assault evidence tracking system (TrackKit). The collection details must be entered into TrackKit within two business days after the exam. The tracking system allows patients to follow the location and status of the evidence (Texas Government Code §420.034).

Patient History

The examiner explains to the patient that the history is intended to document what happened in order to offer appropriate treatment and to determine what parts of the body to collect evidence from. For adolescent or adult patients, the examiner asks them to describe what happened from just before the sexual assault occurred to when they arrived at the facility. For prepubertal children, the examiner avoids extensive interviewing if they are not a trained sexual assault nurse examiner, specially trained medical forensic professional, or specially trained forensic physician.

DOCUMENTING EVIDENCE

Documentation in the medical forensic record is critical not only for victim care in the aftermath of sexual assault but also in the investigation of the crime and processing of any evidence collected during the exam (DOJ, 2017).

Findings are documented on whichever form has been adopted by the facility. Forms may be included in the SAEK or are downloadable from the Texas Evidence Collection Protocol (see “Resources” at the end of this course).

All evidence must be properly documented using verbal descriptors, diagrams, and photographs, as applicable. Documentation typically includes both a narrative and the use of a body chart, labeled appropriately. When documenting the history:

- Use the patient’s own words in quotation marks for greatest accuracy. If a patient uses a slang word, clarify the meaning. For example, the nurse might document, “The patient states, ‘He nutted in me,’” and then add, “The patient clarified that ‘nutted’ refers to ejaculation.”

- Avoid judgmental words. Documentation should avoid passive tense because the meaning may not be as clear to the reader. Also, do not include expressions such as “the patient alleges” or “the patient refuses” because they imply a nonobjective conclusion about what the patient has stated. Nonjudgmental documentation alternatives include “the patient states or reports” or “the patient declines.”

(Johnson, 2019; Sheridan, 2017)

Physical Assessment

The forensic medical assessment includes assessing and documenting any injuries that may have resulted from blunt or penetrative trauma, suction, bites, cuts, lacerations, abrasions, burns, bruises, or contusions. It is important to use the correct term when documenting findings. Common terms as described in the Texas Evidence Collection Protocol include:

- Abrasion: Scraping type of injury that is superficial damage to skin or mucous membrane

- Bruise: Bleeding beneath the surface of the skin; an accumulation of blood in the tissues outside of the blood vessels

- Contusion: A bruise (see above)

- Cut: An opening in the skin that occurs when a sharp object comes into contact with skin or tissues with enough pressure to divide it; not the same as a laceration or tear

- Laceration or tear: Injury that occurs when the skin is broken and disrupted by blunt force such as tearing, ripping, crushing, overstretching, pulling apart, over-bending, or shearing of tissue

- Petechiae: Multiple hemorrhagic spots, pinpoint to pinhead in size

- Scar: Fibrous tissue that replaces normal tissue after the healing of a wound

(James et al., 2014; Faugno et al., 2012; U.S. Army, 2017)

STRANGULATION

Strangulation is a medical emergency that requires physician evaluation prior to or during collection of forensic evidence. The following indicators constitute physical evidence of strangulation that should be documented and, if appropriate, photographed:

- Bruising, redness, swelling

- Shortness of breath, wheezing, sore throat, raspy voice

- Scratches on the neck

- Petechiae to conjunctiva, mouth, face, or neck (any area above the constriction)

- Bruising or petechiae behind the ear

- Loss of consciousness or memory of incident

- Loss of urine or stool

A victim of strangulation may have no external evidence of being strangled and may still develop life-threatening sequelae. Strangulation has been identified as a predictor of homicide in intimate partner relationships and is a red flag for healthcare professionals (Ketchmark, 2020).

Physical Evidence Collection

Physical evidence consists of articles that can be collected for analysis of a crime. Types of physical evidence may be:

- Biologic (e.g., blood, skin, hair, semen, saliva, vegetation)

- Trace evidence (e.g., fiber, glitter, glass, soil, sand, adhesive, gravel, oil)

- Gross (i.e., visible to the eye) (e.g., soil under the fingernails)

- Invisible (e.g., DNA on the skin surface)

Following are some important guidelines for the collection of physical evidence for forensic purposes:

- Bring all necessary equipment into the room before beginning the physical assessment.

- Always maintain Standard Precautions when obtaining biological evidence. This means always wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves and gown (or clean lab coat) and a facemask and eye protection if there is any potential for droplet splatter.

- Treat all biological evidence as a biohazard to prevent possible exposure to HIV or other pathogens.

- Best practice is to use two swabs held together when swabbing each sample.

- Use a least-invasive to most-invasive procedure process.

(Texas A&M, 2022)

Detailed instructions and a flowsheet for both the Adult/Adolescent Assessment and Prepubertal Pediatric Assessment are found in the Texas Evidence Collection Protocol (see “Resources” at the end of this course). The protocol guidelines also include directions when there is no need to collect specific evidence and for assisting survivors of human trafficking, intimate partner violence, and strangulation. The table below provides a summary.

| Items | Collection Procedure |

|---|---|

| (Adapted from Texas A&M, 2022) | |

| 1. Clothing collection |

|

| 2. Debris and foreign material collection |

|

| 3. Observation of skin surfaces |

|

| 4. Oral and buccal specimens |

|

| 5. Blood and urine specimens |

|

| 6. Head hair combings and head hair controls |

|

| 7. Additional swabs |

|

| 8. Fingernail swabs |

|

| 9. Pubic hair combings |

|

| 10. External genitalia swabs |

|

| 11. Orifice swabs (vaginal/cervical/rectal) |

|

Preserving Sample Integrity and Security

In order to preserve the integrity of the samples:

- Maintain the individuality of the sample. Preserve each sample separately to avoid contamination. Individual samples for a single case are to be separated, as are samples taken from multiple cases. Maintaining a physical boundary between simultaneous evidence-collection processes among more than one patient in a busy emergency department will reduce the likelihood of a mix-up. A clinician should never simultaneously collect evidence from more than one patient, since cross-contamination could occur and jeopardize any criminal case. It is important to change gloves frequently, changing each time before handling a new piece of evidence.

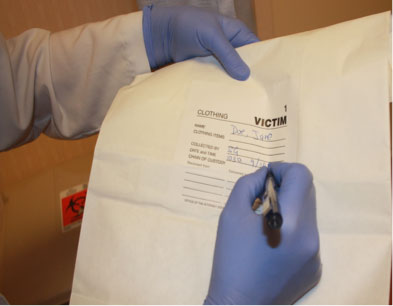

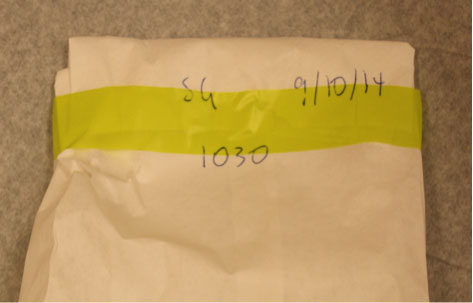

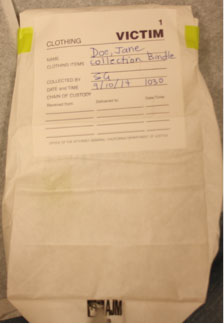

- Label each sample. All evidence should be labeled with the patient’s name, date of birth, and identifier number; description of the contained evidence and where it was recovered; and the examiner’s initials, date, and time (Texas A&M, 2022). In addition, any evidence containing blood or other body fluids must be labeled as a biohazard. Glass or other sharp objects should also be identified on the outside of the container.

- Maintain evidence security. Collected evidence should remain in plain view of the clinician or in an established location in the emergency unit. Never leave evidence unattended and accessible to tampering. Document custody transfer to the police on the appropriate forms when releasing the SAEK and clothing to law enforcement.

Detailed instructions for preparing and sealing a nonreport SAEK for mailing are included in the Texas Evidence Collection Protocol (see “Resources” at the end of this course).

CHAIN OF CUSTODY

The chain of custody is a process used in forensic evidence collection that provides accurate information about who collected and transported physical evidence. A good chain of custody preserves the evidence against possible contamination or tampering. This process tracks the places the evidence has been kept and the people who have had contact with the evidence, in chronological order. The nurse assures that the evidence has been secure throughout the process of obtaining, labeling, packing, sealing, and processing in order to be defensible in the criminal justice system.

The chain of custody documentation includes:

- Receipt

- Storage

- Transfer of evidence

- Printed name and signature of each person in possession of and transferring or receiving custody

(Texas A&M, 2022)

EVIDENCE STORAGE

Biological evidence may need to be stored before shipment to a crime laboratory for analysis. Check with the local crime lab for specifics. Follow these basic guidelines for storing biological specimens:

- Completely dry wet or moist items before packaging them in a sterile and secure environment. If items cannot be completely dried before the exam is finished, refrigerate as soon as possible.

- Package in paper, not plastic. Plastic is nonporous and therefore allows for moisture retention, resulting in possible growth of bacteria, mold, and/or mildew.

- Refrigerate sexual assault kits. The refrigerator should be locked or located in a locked room that is dedicated to evidence storage.

- If in doubt about how to store biological evidence, refrigerate it while awaiting further instructions or transport.

(Texas A&M, 2022)

Photographic Evidence

Photographs can be an important part of forensic evidence and may be used in some legal proceedings to demonstrate physical findings. Facilities must have policies in place to guide collection and appropriate secure storage of digital images, and written informed consent must be obtained from adult patients prior to taking photographs.

Informed consent from the adult parent or guardian should be obtained for pediatric patients, and assent should be obtained from the child before obtaining photographs if possible. However, under Texas Family Code 32.005, photographs, X-rays, and blood tests may be obtained from a child without consent if a physician, dentist, or psychologist has reason to believe that a child has been abused or neglected (Texas A&M, 2022).

Patients have the right to know how photographs will be stored and utilized and should be reassured that photographs are for medical forensic purposes only. When photographs are taken, experts may render opinions without the need for the patient to undergo multiple exams. Any patient who does not want to be photographed has the right to decline (Texas A&M, 2022).

In addition, Texas Government Code 420.032 requires that a health professional must either use photo-documentation when a child is reported to be the victim of a sexual assault or document why no images were obtained in the medical record.

Each institution should have policies in place for obtaining and releasing photographs. For example, the policy might require written consent or a subpoena to release anogenital images rather than routinely being given to law enforcement. Personal photography equipment/phones are not used because chain of custody and confidentiality of photographs cannot be maintained (Texas A&M, 2022).

No photographs of the anogenital area should be taken unless the clinician is a specially trained medical forensic professional. If the clinician has not had this training, the photographs should include only the head and extremities.

Basic photographic guidelines include:

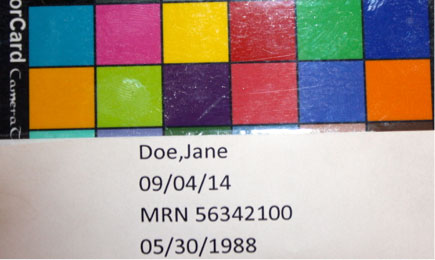

- Take a picture of the patient’s demographic information (name, date of birth, age, etc.). A hospital-generated patient label works well for this purpose. This photo should be the first photo of the series and serves to identify the set of photographs. Alternatively, a unique identification number may be used per the institution’s policy. A professional color card may also be considered if color quality of photos is questioned later.

Photo of the patient’s demographic information and color card. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

- Whenever possible, include a photo of the patient’s face as the second photo in order to establish identity. This will help the examiner recall the patient at a later time if the case goes forward.

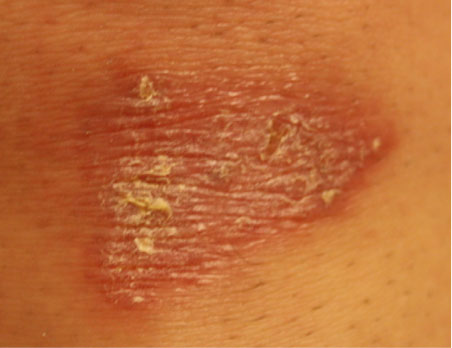

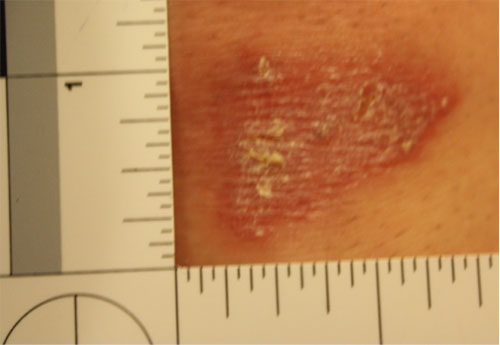

- In the photo of an injured area, always include an object of measurement (a scale) such as a ruler, paper measuring tape, or swab wrapper with centimeters printed on the side. Photograph the injury with and without the scale.

- Take a series of three photos for each injury: 1) a regional photo to show the anatomic location (e.g., middle of the back, right shoulder, etc.); 2) medium range photo, capturing a closer view of the injury; and 3) close-up of the injury. Each close-up of the injury should be photographed with and without a scale beside it (Texas A&M, 2022).

- Include a written report that describes the findings depicted in the photographs. Add a notation that states who took the photos, what type of camera was used, and details such as the magnification used.

A regional photo depicts an abrasion on the patient’s left knee. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

A medium-range photo shows the abrasion on the left knee. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

A close-up photo of the abrasion without a scale. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

A close-up photo of the same abrasion with a scale. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Clothing Evidence

The clothing worn by an individual often contains physical or biological evidence that must be preserved. If the patient is still wearing the clothes they had on during the event, all items can be considered evidence. If the patient has changed their clothes, the nurse should collect the underpants that the patient wears to the exam since transfer of internal evidence from a sexual assault may be present on the fresh underpants. Examine the patient’s clothing and document any obvious stains or tears (Texas A&M, 2022).

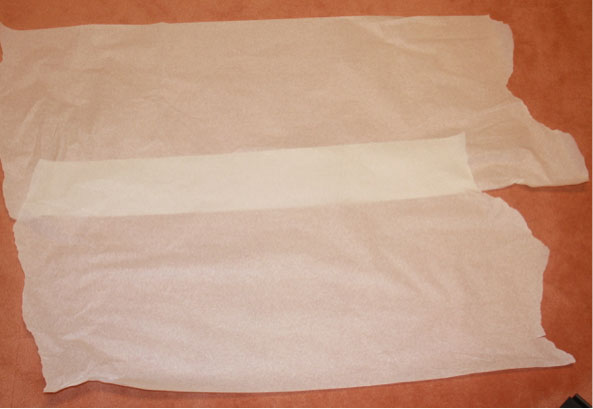

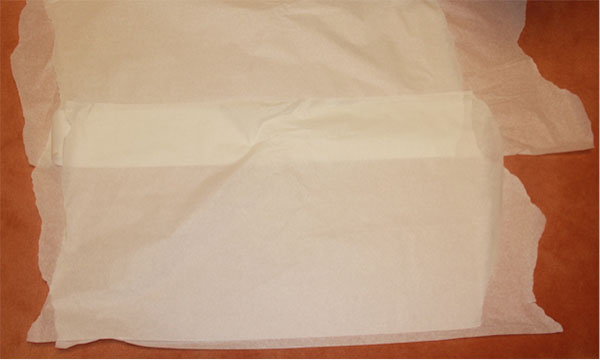

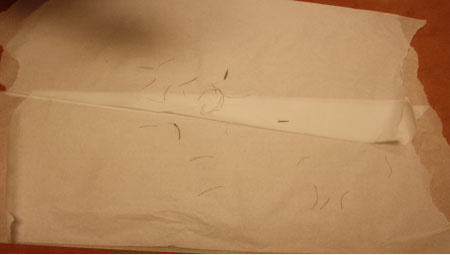

Clothing evidence is gathered and packaged for further evaluation as described below:

- Begin by covering the floor with a layer of exam table paper or a folded hospital sheet. The purpose of this bottom layer is to prevent collecting evidence from the emergency department floor; this layer will not be collected. When collecting wet evidence, a waterproof pad may be used as a bottom layer.

- Cover with another layer of paper. A large paper sheet for this purpose is found in some SAEKs, or exam table paper may be used. This layer will catch any debris that may fall from the patient’s clothing, such as hair, vegetation, etc., and will be folded into a bindle and collected after the patient has undressed. If the patient has many clothing items, this area will need to be fairly large.

- Have the patient slip off their shoes and step directly onto the paper with bare or stocking feet.

- The patient may remove clothing from the top of the body first and drop it onto the paper below. After the patient has removed all of the clothing from the top of the body, they can dress in a hospital gown and then remove the clothing from the lower part of the body, following the same process.

- Using a clean pair of gloves for each item of clothing, inspect the clothing for tears and stains. Place a hospital sticker on the item of clothing after marking the sticker with the time the clothing was collected and the examiner’s initials.

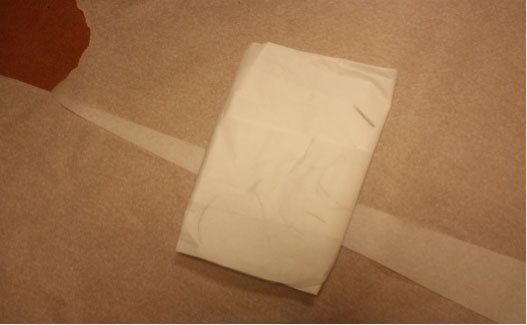

- Package each article of clothing separately. Be sure to seal the bag with tape over the edge of all openings. Write the time, date, and examiner’s initials across the seal. Mark the bag with the patient’s name, what clothing is in the bag, any information about the clothing, who collected it, and when it was collected. Number each bag “1 of 2, 2 of 2,” etc.

- After the clothing is collected, be attentive to any debris that might be shaken from the clothing. This material should be packaged as trace evidence. Be careful to keep items separated for packaging.

- Fold the top layer of paper, if debris is visible, into a bindle. Label with the patient’s name and the collector’s initials, and package in a separate clean paper evidence bag as described for clothing above.

Bottom layer of paper. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Second layer of paper. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Patient stepping on paper with stocking feet. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Patient beginning to disrobe and dropping articles of clothing onto the paper. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Patient donning hospital gown and continuing to drop articles of clothing onto the paper. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Examiner labeling articles of clothing. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Examiner labeling the bag. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Sealed bag with examiner’s initials, date, and time written across the seal. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Trace evidence (hair) that has fallen from the patient’s clothing onto the paper. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Folded paper bindle. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

Evidence packaged in a paper bag and properly labeled. (Source: Sheree Goldman.)

To avoid transferring evidence from one piece of clothing to another, place each piece of clothing in a separate evidence bag. Only the underwear is sealed in the SAEK. Air dry any wet clothing before packaging, and use paper evidence bags. If it is not possible to dry the clothing, refrigerate as soon as possible (Texas A&M, 2022).

Collecting Other Evidence

Other evidence may include hair, fibers, and foreign material such as leaves, dirt, sand, or glass. This evidence can create a link between a victim, a suspect, and a crime scene and may be important for law enforcement in piecing together what has happened.

HAIR

Hair is present in a wide variety of forensic situations. For instance, during an assault, hairs may transfer from one individual to another.

Use an evidence comb from the SAEK, and place a paper towel under the patient’s head or buttocks to collect the loose hairs that result from the combing. Include the comb, paper towel, and any hairs that are collected in a bindle, which is sealed in an envelope that is appropriately labeled and sealed. If foreign hairs are collected, control hairs from the patient may be collected by cutting and sealing in an envelope that is appropriately labeled and sealed. Pulling hairs is no longer recommended (Texas A&M, 2022).

FINGERNAILS

Fingernails may contain foreign DNA in the event the patient describes scratching the suspect. It may also contain DNA from the victim or trace evidence such as fiber, dirt, or vegetation. Lightly moisten two small swabs with sterile water, and swab under and around the fingernails, holding both swabs together. Use one set of swabs for each hand, swabbing all five fingers on each hand with the same two swabs (Texas A&M, 2022).

DEBRIS

Bindle any other debris (e.g., tape residue, vegetation, sand, glitter) and place in an envelope that is labeled with the collection site and description. Seal the envelope with the examiner’s initials and place it in the SAEK (Texas A&M, 2022).

TOXICOLOGY

Urine and/or blood should be collected when a toxicology study is indicated, such as in cases that may include drug-facilitated sexual assault. Urine should be frozen or refrigerated. Document in the medical record any toxicology specimens obtained. Label specimen containers, and document the exact collection time (Texas A&M, 2022).

PROVIDING PROFESSIONAL SUPPORT AND REFERRAL

A traumatized patient will most likely need professional support beyond what can be provided in the emergency department. Sexual assault victims, in particular, have increased risk of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, and suicidal thoughts (RAINN, 2020). All traumatized patients, then, should be linked with resources to attend to their psychological distress.

Printed information about confidential counseling and crisis intervention sources should be made available to the patient and/or family. They are often unable to digest and respond to large amounts of information and direction in the initial period after the trauma. The nurse may offer to contact outside services directly to set up a first appointment. By offering options and promoting informed decision-making, the patient is assisted through the early stages of their crisis (DOJ, 2013).

CASE

Julie, 20, arrives at the emergency department at 9 a.m. She self-reports that she thinks she was sexually assaulted at a party the night before. She is well-groomed and picking at her fingernails.

Julie explains to the nurse that she doesn’t remember much about the incident except for a flashback of seeing a naked man hovering over her on a sofa. She had been drinking and thinks there might have been something put in her drink. She showered and ate breakfast that morning before coming to the hospital.

The nurse asks if Julie has notified law enforcement. Finding that she has not, the nurse obtains Julie’s permission to have an officer come to the emergency department to take a statement. The nurse also calls a certified rape crisis counselor to the hospital to provide support and asks Julie if there is anyone else she would like to contact.

The nurse informs Julie that she can collect basic evidence at the hospital or arrange for Julie to be seen by a certified Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner at a center 100 miles away. Julie chooses to remain at the hospital and signs a consent for a forensic exam. The nurse obtains a detailed history from Julie in a private exam room, being sensitive to let Julie lead the discussion. The nurse documents the history using as many of Julie’s own words as possible.

Even though Julie has changed her clothing since the assault, the nurse collects and packages Julie’s underwear for evaluation. The nurse performs a head-to-toe evaluation of Julie, looking for injury and any biological or physical evidence for collection. Julie has a bite mark on her right shoulder and bruising on both her upper arms and ankles. The nurse carefully documents these on the body diagram and, with permission from Julie, photographs them. The nurse swabs the bite mark area with two lightly moistened swabs held together in case saliva is remaining on the skin surface.

Once the physical examination is complete, the nurse explains to Julie the need for a body orifice examination in order to collect potential biological evidence. The nurse arranges for the physician to assist with the speculum portion of the exam. The nurse proceeds according to the Texas protocol, collecting swabs and packaging them in swab boxes and envelopes from the sexual assault evidence kit (SAEK). The nurse keeps the evidence in view until the evidence collection process is completed, and then seals the SAEK.

The full forensic examination and specimen collection takes around two hours. Julie is also offered the option to undergo lab work and obtain medications to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, following CDC guidelines. The examiner reviews several crisis intervention options for Julie, provides her with written materials, and calls to make an appointment with a counselor in three days.

PROVIDING TESTIMONY

Nurses may be called upon to provide testimony in a court case involving evidence that they have collected. The following are recommendations:

- If subpoenaed to testify, prepare adequately by reviewing the written documentation and meeting with the attorney who is requesting the testimony in advance of the hearing.

- Listen carefully to the questions that are asked and consider a response before answering. Pausing to think through the question shows a thoughtful observer and reporter.

- When considering the response to a question, be thorough, but do not provide any additional or extraneous information unless expressly asked for clarification.

- Never make up facts about a case. It is better to say “I do not recall” rather than state something that is false or inaccurate.

- Maintain a calm demeanor and answer all questions honestly.

By being objective, professional, and thorough, a nurse can successfully participate in obtaining justice through the court system (La Monica & Pagliaro, 2013).

CONCLUSION

Nursing skills, such as obtaining a history, conducting a physical assessment, and collaborating with other disciplines, allow nurses to participate in evidence collection while being sensitive to the physical and psychological needs of patients who report being sexually assaulted.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Lauren DaSilva, Executive Director of Monterey County Rape Crisis Center, for assistance with photos.

RESOURCES

Texas Abuse Hotline (Department of Family and Protective Services)

(to report abuse)

800-252-5400 (toll-free, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week)

Texas Adult Evidence Collection Flowsheet

Texas Pediatric Evidence Collection Flowsheet

Texas Evidence Collection Protocol

Texas Health and Human Services

(to report abuse in nursing homes, assisted living centers, day activity and health service facilities)

800-458-9858

Translation Services

Translation Services

Translation Services

Translation Services

REFERENCES

NOTE: Complete URLs for references retrieved from online sources are provided in the PDF of this course.

Advocate Editorial Board. (2018, February 21). Shortage of sexual assault nurses is a public health issue. Victoria Advocate. https://www.victoriaadvocate.com

Faugno DK, Copeland RA, Crum JL, & Speck PM. (2012). Advanced-level adolescent and adult sexual assault assessment: SANE/SAFE forensic workbook series (1st ed.). STM Medical Publishing.

International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN). (2020). Victim centered care. SAFEta.org

James SH, Nordby JJ, & Bell S. (2014). Forensic science: An introduction to scientific and investigative techniques (4th ed.). CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group.

Johnson C. (2019). When documenting a sexual assault, words matter. Gov1. https://www.gov

Ketchmark S. (2020). All abusers are not equal: New IPV research reveals an indicator of deadly abuse. Training Institute on Strangulation Prevention. https://www.strangulationtraininginstitute.com

LaMonica P & Pagliaro EM. (2013). Sexual assault intervention and the forensic examination. In RM Hammer, B Moynihan, & EM Pagliaro (Eds.), Forensic nursing: A handbook for practice (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC). (2022, June 28). California’s LGBT population. https://www.ppic.org

Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). (2020). Effects of sexual violence. https://www.rainn.org

Sheridan D, Nash K, & Bresee H. (2017). Chapter 16: Forensic nursing in the emergency department. Nurse Key. https://nursekey.com

Sirchie. (2023). Sexual assault victim evidence collection kit. https://www.sirchie.com

Texas A&M University, College of Nursing. (2022). Texas evidence collection protocol. https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov

U.S. Army Medical Department Center and School. (2017). Sexual assault medical forensic examiner (SAMFE) inter-service course: Student workbook.

U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). (2017). National best practices for sexual assault kits: A multidisciplinary approach. https://www.ncjrs.gov

U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). (2013). A national protocol for sexual assault medical forensic examinations, adults/adolescents (2nd ed.). (NCJ 228119). U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.ncjrs.gov

Customer Rating

4.9 / 1377 ratings