Dementia: Alzheimer's Disease Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

Fulfills IL, KY, MA, and RI Alzheimer's and dementia training requirements. 1-contact-hour course on Alzheimer's disease. Discusses diagnosis, stages, and medical and pharmacological treatments for cognitive and memory-related symptoms. Learn about providing appropriate care and management of the AD patient and managing challenging behaviors.

Course Price: $10.00

Contact Hours: 1

Course updated on

January 14, 2025

"Very informative, helpful for providing a better approach when treating AD patients." - Jessica, RN in RI

"Excellent self-learning course. Appreciated the evidence-based information." - Janet, RN in New Jersey

"Excellent information! I enjoyed it very much and learned a lot." - Mary, RN multi-state licensed

"Great CEU. Information organized well and easy to follow." - Jody, RN in Texas

Dementia: Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will have increased your knowledge of diagnosis, treatment, and care for persons with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Identify the warning signs and symptoms of dementia.

- Describe the elements involved in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.

- Discuss current treatments.

- Outline management and care for individuals with AD.

- Identify effective communication strategies for patients with AD.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

RECOGNIZING ALZHEIMER’S

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of a group of disorders called dementias, brain failures characterized by progressive cognitive and behavioral changes. Alzheimer’s disease results from a complex pattern of abnormal changes, develops slowly, and gradually worsens. The course of Alzheimer’s and the rate of decline vary from person to person. Alzheimer’s disease can be present for many years before there are clinical signs and symptoms of the disease. On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives for four to eight years after diagnosis. However, some may live for as many as 20 years (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024a).

Cognitive aging is normal and does not involve abnormal changes to the brain. Signs of normal aging might include making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills, misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them, or becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted. Other cognitive changes may be early signs of Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024b).

The cardinal signs and symptoms of dementia include:

- Memory impairment that disrupts daily life

- Executive function and judgment/problem-solving impairment

- Behavioral and psychological symptoms

10 WARNING SIGNS OF ALZHEIMER’S

- Memory loss that disrupts daily life

- Challenges in planning or solving problems

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks at home, at work, or at leisure

- Confusion with time or place

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relations

- New problems with words in speaking or writing

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps

- Decreased or poor judgment

- Withdrawal from work or social activities

- Changes in mood and personality

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024i)

DIAGNOSING ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

An early and accurate diagnosis of dementia is important in order to identify those eligible for disease-modifying treatments. It also aids those with dementia in understanding what is happening to them and how to manage their condition.

There is no single test that can diagnose Alzheimer’s disease, and tests used to diagnose dementia are not always accurate. It can take months or even years to get the right diagnosis (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024b).

Diagnosis is based on:

- Medical history

- Physical examination

- Neurologic examination

- Mental cognitive status tests

- Diagnostic laboratory tests (to rule out other health issues that can cause similar symptoms to dementia)

- Brain imaging

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024b)

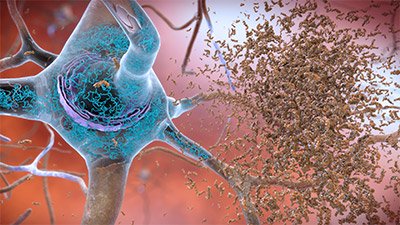

NEUROFIBRILLARY TANGLES AND AMYLOID PLAQUES

Neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques are two characteristic lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. These lesions occur in areas of the brain in normal aging but to a greater extent in Alzheimer’s disease (Taffet, 2023).

Neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques. (Source: National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health.)

Mental Cognitive Status Testing

The two most widely used tools for cognitive assessment are:

- Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), which assesses multiple cognitive domains, particularly memory and language (Dementia Care Central, 2024)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment, which assesses seven domains of cognitive function (Rosenzweig, 2024).

Blood Test for Alzheimer’s Disease

A recently developed blood test specific for diagnosing Alzheimer’s is the PrecivityAD2, a biomarker that detects an abnormal version of the tau protein found in neurons affected by Alzheimer’s. Tiny amounts of this protein make their way out of the brain cells and into the bloodstream. The test measures the ratio of two types of amyloid beta as well as the proportion of a specific type of tau called p-tau217 (Hamilton, 2024; Stanford Medicine, 2024).

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

EEG can be used as a screening tool for diagnosis and disease progression evaluation of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. The most prominent effects of AD-linked neurodegeneration on EEG metrics were localized at parieto-occipital regions (Jiao et al., 2023).

Imaging Studies

Structural neuroimaging examines the physical structure of the brain by measuring brain tissue volume and identifying areas of atrophy. It includes:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT scans), the most commonly used to rule out other conditions that may cause symptoms similar to Alzheimer’s

- Positron emission tomography (PET), typically used in a research setting

(Mayo Clinic, 2024)

Molecular imaging modalities include positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), which can help narrow down a diagnosis by revealing deficits common in Alzheimer’s disease that are distinct from other dementias. Amyloid PET scanning makes amyloid plaques “light up” on a brain PET scan, enabling, for the first time, accurate detection of plaques in living people (UCSF, 2024a; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024b).

Functional Assessment

Functional status can be assessed using valid and reliable instruments, including:

- Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale

- Barthel ADL Index

- Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living

- Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ)

- Functional Independent Measures (FIM)

- Performance Assessment of Self-care Skills (PASS)

(Physiopedia, 2024)

PHARMACOLOGIC AND MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Currently, there are no medications that can cure Alzheimer’s, but there are approved treatments addressing the underlying biology of the disease. Other medications may help lessen symptoms. These medications fall into two categories:

- Drugs that change disease progression in early AD

- Drugs that temporarily mitigate some symptoms

FDA-approved anti-amyloid medications for treating the cause of Alzheimer’s disease include:

- Lecanemab (Leqembi), an intravenous infusion therapy given every two weeks to treat early Alzheimer’s disease

- Donanemab (Kisunla), an intravenous therapy administered every four weeks for those with mild cognitive impairment or dementia

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024c)

ADUCANUMAB (ADUHELM) DISCONTINUED

Aducanumab (Aduhelm) received accelerated approval from the FDA to treat early Alzheimer’s as the first therapy to show that removing beta-amyloid from the brain reduces cognitive and functional decline in people with early Alzheimer’s disease. However, Aducanumab was discontinued on November 1, 2024, so the manufacturer can “reallocate resources to other Alzheimer’s disease treatments” (Brockman et al., 2023; Biogen, 2024).

Treating Cognitive and Memory-Related Symptoms

As Alzheimer’s progresses, medications may help temporarily lessen or stabilize symptoms related to memory and thinking by affecting chemicals involved in carrying messages among and between the brain’s nerve cells (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024c). These include:

- Cholinesterase inhibitors donepezil (Aricept), rivastigmine (Exelon), and galantamine (Razadyne), for treating symptoms related to memory, thinking, language, judgment, and other thought processes

- Glutamate antagonist, a combination of donepezil and memantine, for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease

- Antioxidant vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol), for delaying progression of functional decline in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, but with no measurable effect on cognitive performance

(Press & Buss, 2024)

Treating Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms

Behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms are often more problematic than memory impairment.

Suvorexant (Belsomra) is approved for insomnia. Other medications are used “off label,” including:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Anxiolytics

- Benzodiazepines

- Antipsychotics, only after other drugs have been tried

- Analgesics (preferably nonopioids for mild persistent pain)

- Opioids, for moderate to severe pain

(OPG, 2024)

MANAGEMENT AND CARE FOR THE PERSON WITH ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Supportive care focuses on preventing and relieving suffering and on providing the best quality of life for patients and their families facing serious illness.

Providing a Safe Home Environment

As dementia progresses, physical and social environments prove more difficult, and a safe environment is essential. Things to consider include:

- Adding strong, low-glare lighting, and night lights; arranging lights to prevent or minimize shadows; and using motion-activated lighting in hallways and bathrooms

- Covering all electric outlets

- Lightening the color of walls to reflect light and contrast with the floor and avoiding busy patterns

- Marking the edges of stairs with brightly colored tape

- Limiting the size and number of mirrors, which may confuse a person with AD

- Placing decals at eye level on sliding glass doors and picture windows

- In the bathroom:

- Installing:

- Free-standing or built-in shower chair or a bathtub transfer seat

- Grab bars

- Handheld shower

- Temperature-controlled and motion-activated water faucets

- Large nonskid bath mats

- Raised toilet seat

- Removing the lock from the door

- Securing medicine in a lockbox

- Blocking access to cleaning supplies and razors

- Setting the water heater to 120 ËšF

- Installing:

- In the bedroom:

- Installing an audio (“baby”) monitor

- Removing the door lock

- Installing bed rails or a hospital bed

- Placing a bell or a horn at bedside to summon help

- Using motion-activated night lights

- In hallways and stairs:

- Installing railings on both sides of a staircase

- Ensuring carpets on stairs are not loose

- Using sturdy, nonslip pads or double-sided tape to affix rugs to the floor

- In the kitchen:

- Disconnecting the garbage disposal and microwave

- Locking cabinets with childproof locks

- Regularly checking the pantry and refrigerator for spoiled food

- Installing temperature-controlled and motion-activated water faucets

- Installing childproof knob covers and devices that turn off a cooktop, oven, or range after a set time

- Placing certain regularly eaten food items within reach and stashing other foods out of sight

- Discarding toxic plants and decorative fruits

- Locking up all supplements, medications, sugar substitutes, and seasonings

- In the living room and home office:

- Anchoring bookcases to the wall

- Clearing surfaces

- Considering adaptive furniture such as motorized lifts

- Installing combination or key locks on rooms and storage places containing potentially dangerous/hazardous items

- Keeping car keys out of reach

- Storing firearms in a gun safe or off the property

- Listing emergency phone numbers near all phones

(Van Dyke & Dono, 2023; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d)

Supporting Basic Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

The tasks of daily living can be frustrating and overwhelming, as they are often quite complicated when broken down into steps.

Supporting these tasks involves:

- Activity analysis (task breakdown), to determine and organize manual and cognitive activities involved in the task

- Verbal coaxing, to perform and retain abilities longer

- Providing cues, such as labeling, placing clothes in view, and demonstrating tasks

- Establishing and maintaining a routine, to help retain learned skills and reduce the need for assistance

- Offering choices, e.g., asking “when” instead of “if” the person wants to bathe

BATHING AND ORAL CARE

- Avoiding discussing whether or not a bath is needed

- Trying again later if the person adamantly refuses to bathe now

- Providing partial baths between baths or showers

- Following the person’s previous routines, including time of day and type of bathing

- Preparing the bathroom in advance

- Checking water temperature

- Talking through and completing one step at a time

- Being calm and gentle; not rushing

- Using a seat and hand-held shower attachment

- Introducing warm shower water gradually, starting at the feet and moving up the body

- Using dry shampoo products

- Using electric razors

- Using oral care swabs with diluted hydrogen peroxide solution

- Providing fruit such as apples to help clean the teeth

(Piedmont Healthcare, 2024; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e)

DRESSING AND GROOMING

- Providing simple garments with large zipper pulls, Velcro fasteners, and few buttons, and pull-on pants and shirts

- Using cardigan sweaters instead of pullovers

- Laying out clothes in the order in which they will be put on

- If needed, providing constant repetition of each step

- Using nonskid shoes, such as washable rubber-sole shoes with Velcro fasteners, or slip-ons

- Continuing regular grooming routines and favorite beauty shop or barber

- Maintaining preferred hairstyles, beards, and makeup

- Assisting with combing hair, trimming fingernails, shaving, etc.

- Performing tasks along with the person with encouragement to copy

- If the person wants to wear the same clothes every day, providing duplicates

(Piedmont Healthcare, 2024; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e)

TOILETING

- Checking the location of mirrors (to avoid confusing a reflection for someone else in the room)

- Removing objects that can be mistaken for a toilet

- Providing a bedside commode or urinal, especially at night

- Posting a colorful sign on bathroom door for easy identification

- Setting a regular bathroom schedule

- Monitoring mealtimes and foods consumed to help predict bathroom need

- Respecting privacy as much as possible

- Assisting with removing or adjusting clothing

- Helping with positioning

- Giving cues or talking through each step

- Setting a urinary alarm system for reminders

When the person loses bowel or bladder control, medical evaluation is necessary to rule out conditions including urinary tract infection or medication side effects. When they are incontinent, consider:

- Restricting fluid and caffeine intake 2–3 hours before bedtime

- Using incontinence aids at night (i.e., disposable briefs, pads for beds/chairs, condom catheters)

- Dressing the person in manageable clothing and considering eliminating underwear

Constipation and fecal impaction can cause great discomfort and lead to behavioral problems. It is important to continually assess and monitor bowel function. Avoid laxatives, and encourage a high-fiber diet (Piedmont Healthcare, 2024; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e).

EATING

Eating habits and behaviors change during the course of Alzheimer’s disease and may be caused by physiologic or psychological factors. Proper nutrition reduces the risk of constipation, dehydration, and vitamin deficiency, which contribute to increased confusion and a decline in physical functioning.

Supporting the Eating Process

Strategies to assist the person to eat and enjoy the process include:

- Providing a quiet, relaxing, well-lit, homelike atmosphere

- Maintaining familiar dining routines

- Reducing distractions

- Playing soothing music

- Facilitating social eating in the earlier stages of the disease; limiting social stimulation in the later stage

- Allowing choice of mealtimes; adjusting times based on agitation or disorientation

- Offering food choices, but limiting the number

- Putting one utensil and one food in front of the person at a time

- Offering culturally appropriate foods

- Keeping the table free of clutter

- Using white dishes to help distinguish food from the plate and contrasting placemats to help distinguish the plate from the table

- Providing bendable straws or lidded cups

- Checking food temperature

- To prevent overeating, limiting access to food between meals, maintaining a schedule, and monitoring intake

- Providing ample time to eat; not rushing

- Ignoring messy eating

- Sitting to the side and level to the person, making eye contact, and talking while assisting

- Modeling eating sequence, with reminders to eat slowly and chew thoroughly

- Offering swallowing reminders

- Providing verbal prompts or physical cues to encourage eating

- Encouraging independence

- Adapting foods (e.g., finger foods) and providing assistance when utensils cannot be used

- Matching foods and beverages to swallowing capability

- Using adaptive devices/utensils

- Using hand-over-hand feeding

(Piedmont Healthcare, 2024; Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e)

Maintaining Nutritional Well-Being

- Providing a balanced diet and variety of foods

- Limiting foods with high saturated fat and cholesterol

- Offering nutrient-dense foods

- Reducing refined sugars, but for loss of appetite, adding sugar to encourage eating

- Substituting spices or herbs for sodium

- With loss of appetite or weight loss, adding supplements between meals

- To maintain hydration, encouraging fluid intake or providing foods with high water content

- Encouraging simple exercises to increase appetite

- Reviewing medications for drugs that may affect appetite

- Assessing for vision problems that may cause confusion

- Assessing for depression

Ensuring Proper Swallowing

- Giving reminders to swallow with each bite and demonstrating how

- Gently stroking the throat to promote swallowing

- At the end of the meal, checking the mouth to make sure food has been swallowed

- Preparing foods that are easy to chew or swallow (e.g., grinding, cutting into bite-size pieces, serving soft foods)

- Providing thicker or thickened liquids for easier swallowing and less risk of choking or aspiration

- Obtaining a speech-language pathologist’s assessment and recommendations

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e; Piedmont Healthcare, 2024)

AMBULATING

Dementia can affect areas of the brain responsible for motor control, coordination, and balance, causing decreased mobility, increased fall risk, and inability to stand or get up from a chair.

Any physical activity that safely gets a person moving is beneficial. Low-impact workouts may be helpful in improving balance, and music-cued gait training may help increase ambulation speed.

Other strategies include:

- Removing tripping obstacles

- Keeping useful items within reach

- Keeping the house well-lit, especially at night

- Providing nonskid slippers/shoes

Canes and walkers help maintain balance, but can also increase risk of falls if used incorrectly. Provide appropriate training for use of new assistive devices.

In later stages of dementia, the ability to sit up without assistance may be lost, requiring external physical support such an arm rest, lap belt, or other device. Some may eventually become confined to bed or chair. At this point, a health professional should be consulted about specialized equipment options, as well as caregiver education on moving a patient safely (Dementia Care Central, 2023; Alzheimer’s New Zealand, 2024).

Supporting Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs)

Performing IADLs is the first ability to decline with dementia. These include self-care tasks beyond the basics and that require more complex thinking and organizational skills, such as those discussed below.

MANAGING MEDICATIONS

Strategies to manage medications include:

- Combining medications with specific events such as mealtimes

- Using a pill box organizer and medication log

- Using simple language and clear instructions

- For swallowing problems, asking if the medication is available in another form or can be crushed and mixed with food

- Keeping medications stored in a locked drawer or cabinet

- Knowing that herbal therapies and over-the-counter medications can interact with prescribed medications

- Understanding how to determine medication effectiveness

- Knowing which medications are priorities and when a dose can be skipped if necessary

- Giving medications with meals, if allowed, and administering the most important first

- With the prescriber’s approval, giving medications in the morning, when agitation is less likely

- Making certain glasses and hearing aids are worn to minimize confusion

- To cope with resistance, giving medications covertly in food or drink, using distraction, or trying again later

- If resistance is routine, seeking medication options from the provider

- Knowing common medication mistakes (e.g., wrong dose) and when and how to notify the healthcare provider if this occurs

- Calling 911 or poison control in case of suspected overdose

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024f)

SHOPPING AND MEAL PREPARATION

Strategies to assist those living alone or who need extra support with meals include:

- Accompanying the person to stores or shopping online

- Buying frozen or refrigerated ready-to-eat meals or having meals delivered

- Using notes about where certain foods are stored or placing pictures on cupboards or the refrigerator

- Providing simple written instructions for cooking or reheating food

- Planning meals that require no cooking

- If the person is unable to cook safely, keeping the kitchen locked

(Alzheimer’s Society, 2024; Dementia Care Notes, 2024)

DRIVING AND TRANSPORTION NEEDS

Each state has laws and policies regarding physician reporting of driving with dementia to the Department of Motor Vehicles; healthcare professionals should be aware of the regulations in their jurisdiction. When driving is no longer an option, rides can be provided by family, friends, neighbors, public transportation, taxis, or senior and special needs transportation services (Piedmont Healthcare, 2024; FCA, 2024a).

PHYSICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVITIES

Persons with dementia may withdraw from activities, family, and friends. Social and cognitive stimulation may help maintain general well-being and prevent boredom and agitation. Stimulation encourages self-expression, lessens anxiety and irritability, makes the person feel more engaged, and stirs memories. An adult dementia daycare program may be a good option (Piedmont Healthcare, 2024).

MANAGING CHALLENGING BEHAVIORS

Dementia can cause mood swings and changes in personality and behaviors, including agitation and restlessness, vocal outbursts, wandering, sleep disturbances, “sundowning,” and inappropriate sexual activities.

Agitation and Aggression

Agitation is a state of extreme irritability often characterized by hitting, pacing, yelling, cursing, arguing, threatening, and verbal or physical aggression. Triggers may include environmental factors, fear, fatigue, feelings of abandonment, or perceiving that control is being taken away.

An agitated person requires assessment for physical causes of discomfort or pain. The following may also be helpful:

- Providing space and time to calm down

- Avoiding confrontation

- Avoiding criticizing or correcting

- Using a reassuring voice

- Reducing noise, clutter, number of persons in the room

- Maintaining routines and a consistent environment

- Reducing intake of caffeine, sugar, and other energy-spiking foods

- Using gentle touch, soothing music, reading, or taking a walk

- Avoiding use of restraints

- Supporting independence

- Validating feelings and attempting distraction or redirection

- Keeping dangerous objects out of reach

- Using the three Rs: repeat, reassure, and redirect

(FCA, 2024b)

Vocal Outbursts

Disruptive vocal outbursts become increasingly common as Alzheimer’s progresses and the ability to communicate is lost. Verbal outbursts are often triggered by fear, anger, depression, grief, confusion, helplessness, loneliness, sadness, impatience, frustration, physical illness, or discomfort. Environmental factors may include poor lighting, seasonal changes, overstimulation or lack of stimulation, loud noises, or excessive heat.

React by staying calm and reassuring. Validate feelings and try distracting or redirecting attention to something else. Avoid attempts at reasoning.

Interventions to prevent vocal outbursts may include:

- Assessing for pain, hunger, thirst, constipation, full bladder, fatigue, infections, and skin irritation

- Avoiding confrontation or arguing about facts

- Redirecting the person’s attention

- Responding to the emotion, not behavior

- Creating a calm environment

- Allowing adequate rest between stimulating events

- Providing a security object (e.g., item from childhood, photo album)

- Acknowledging and responding to them

- Looking for reasons behind the behavior

- Exploring solutions

- Not taking the behavior personally

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d)

Wandering

At least 6 out of 10 people with dementia will wander at least once. If not found within 24 hours, up to half suffer serious injury or death (ASAC, 2021). The following approaches may be helpful:

- Making time for regular exercise

- Using large-print signs to mark destinations, with a drawing of the activity

- Placing a photo of the person as a younger adult on the room door to help find “home”

- Ensuring doors have locks requiring a key (but locks must be accessible to others and not take more than a few seconds to open)

- Avoiding restraining the person unless there are obvious hazards

- Remaining calm and reassuring

- Avoiding negative commands or arguing with the person

- Masking a door with a curtain, stop sign, or “do not enter” sign

- Painting a door to look like a piece of furniture

- Placing a “Do Not Enter” sign on exit doors

- Painting a black space on the front porch floor that looks like a hole

- Adding “child-safe” plastic covers to doorknobs

- Installing a home security or monitoring system (e.g., GPS tracking device)

- Putting away the person’s coat and purse

- Sewing ID labels in clothes or having the person wear an ID bracelet

- Informing neighbors about wandering behavior and providing them with a phone number

- Having a current photo available in case the need arises to report the person missing

Caregivers can leave a copy of the person’s photo on file at the police department or register the person with the MedicAlert + Alzheimer’s Association Safe Return program, a nationwide emergency response service (FCA, 2024c). (See “Resources” at the end of this course.)

Sleep Issues and Sundowning

Restlessness, agitation, disorientation, and other troubling behavior often worsen in the evening, sometimes continuing through the night. This is referred to as sundowning.

Possible contributing factors include:

- Mental/physical exhaustion

- Biologic clock upset

- Reduced lighting, causing misinterpretation

- Disorientation due to inability to separate dreams from reality

Strategies to help manage sleep issues and sundowning:

- Scheduling major activities for morning or early afternoon

- Encouraging a regular routine of waking up, meals, and bedtime

- Including walks or time outside in sunlight

- Identifying triggers for sundowning events

- Reducing stimulation during evening hours

- Offering a larger meal at lunch and lighter evening meal

- Keeping the home well-lit in the evening

- Avoiding physically restraining the person

- Identifying soothing activities, e.g., listening to music

- Discussing with the provider best times of day for taking medications

- Limiting napping

- Reducing or avoiding alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d)

Perseveration and Compulsive Behaviors

Repetitious speech or actions that occur on a continuous basis and serve no functional purpose may include:

- Repeatedly checking locks, doors, or windows

- Having rigid walking patterns, including pacing

- Collecting/hoarding items

- Counting/organizing objects repeatedly

- Frequent toileting

- Selective eating habits

- Asking the same questions repeatedly

Consider if there is a need that cannot be expressed, e.g., boredom, hunger, or need to use the toilet. Substitute the behavior with another activity, such as folding laundry. Remove or hide objects that might trigger the behavior.

Repetitious activity often has a basis in the past, e.g., going to work. Helpful measures include:

- Distracting with a snack or activity

- Avoiding reminding the person they just asked the same question

- Ignoring the behavior or question, and refocusing onto another activity

- Avoiding discussing plans until immediately prior to an event

- Learning to recognize behaviors that indicate a need to use the bathroom

When the person is very rigid and resistant to interference with the activity, avoid provoking an aggressive reaction.

- Use a calm, matter-of-fact tone of voice.

- Do not become bossy or condescending.

- Distract the person with something appealing to them.

(UCSF, 2024b; FCA, 2024b)

Shadowing is a repetitive behavior in which the person constantly follows a caregiver, who represents security and protection. Suggestions include:

- Establishing and maintaining a daily routine

- Speaking reassuring words often, such as, “You’re safe”

- Avoiding moving or rearranging household furnishings or other items

- Using a whiteboard to indicate the date or when the caregiver will return

- Involving the person in familiar household activities

- Playing favorite music

- Playing a recording of the caregiver’s or other familiar voice

- Playing a videotape of recent events or familiar movies

- Using a daycare center or hiring a professional caregiver

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d)

Inappropriate Sexual Behaviors

Individuals with dementia may lose ability to determine appropriate times, places, or manners to express sexual needs. Inappropriate behaviors may include undressing in public, making lewd remarks or unreasonable sexual demands, and sexual aggression, such as fondling, exposing genitals, or attempting to engage in sex acts with someone other than their partner.

Persons who masturbate in public places should be gently led from the public area to their room. If persons have truly problematic sexual behaviors, visitation should take place in the person’s room. Once the family leaves, immediately involve the person in some activity.

Undressing in public may be due to causes such as pruritus, infection, being too warm, or frustration about remembering how to dress and undress. Clothing that closes in the back makes disrobing difficult in inappropriate settings.

If the person is disruptive or making someone else uncomfortable, make eye contact and say, “Stop,” with a calm but firm tone of voice, and then distract.

If it is thought that the person is seeking more physical affection or intimacy, consider pet therapy, a stuffed animal, and socially appropriate touching such as hand-holding, manicure/pedicure, or brushing/combing hair (UCSF, 2024c).

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES

With Alzheimer’s progression, ability to communicate begins to deteriorate, causing:

- Difficulty finding the right words

- Not understanding what words mean

- Repetitious use of familiar words

- Describing rather than calling familiar objects by name

- Inventing new words for familiar objects

- Losing one’s train of thought

- Reverting to one’s native language

- Problems organizing words

- Reduced speaking efforts

- Relying more on gestures

The following are means to communicate with someone in the early stage of Alzheimer’s:

- Making certain those with vision and/or hearing deficits wear glasses and/or hearing aids

- Avoiding making assumptions about communication ability

- Including the person in conversations

- Speaking directly to the person rather than to a caregiver or companion

- Being patient and taking time to listen to expressed thoughts, feelings, and needs

- Allowing the person time to respond

- Avoiding interrupting

- Asking the person what help may be needed

- Using humor to lighten a mood

In the middle stage of Alzheimer’s, communicating becomes more difficult. Strategies include:

- Engaging in one-on-one conversation in a quiet place

- Speaking slowly and clearly, keeping sentences simple, focusing on one idea at a time

- Facing the person; maintaining eye contact

- Allowing adequate time to respond

- Asking one question at a time

- Asking yes or no questions; avoiding open-ended questions

- Avoiding correcting or criticizing

- Repeating what was said for clarification

- Making statements rather than asking questions

- Avoiding arguing

- Offering clear, step-by-step instructions

- Giving visual cues or demonstrating tasks to encourage participation

- Attempting written notes when spoken words seem confusing

- For a repeated question after it has already been answered, responding once again and then distracting with an activity or new topic

In the late stage of Alzheimer’s, reliance on nonverbal communication may develop. Strategies include:

- Approaching from the front and identifying oneself

- To understand what the person is saying, asking them to point or gesture

- Using touch, sights, sounds, smells, and tastes as a form of communication

- Considering the feelings behind words or sounds

- Avoiding talking down to the person and not talking to others about the person as if they were not present

- Using positive body language

- Repeating the message as often as necessary

- Distracting the anxious or agitated person

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024g)

Nonverbal communication may become the main means to communicate, including:

- Using physical contact

- Sitting or standing at eye level

- Avoiding sudden movements, a stern tone of voice, or tense facial expressions

- Matching body language and facial expression to what is being said

- Learning to recognize a person’s communication through body language

- Using visual prompts such as cue cards or picture book to communicate wants and needs

- Allowing the person to draw to express themself

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d)

CONCLUSION

The risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia increases with age, and as the population continues to age, the number of persons with Alzheimer’s disease will also increase. Healthcare professionals must become educated about this disease and its impact in order to effectively care for these individuals and their loved ones. This includes learning strategies to manage difficult behaviors.

REFERENCES

NOTE: Complete URLs for references retrieved from online sources are provided in the PDF of this course.

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024a). 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024b). 10 early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024c). Medical tests for diagnosing Alzheimer’s dementia. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024d). Medications for memory, cognition and dementia-related behaviors. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024e). Treatments for behavior. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024f). Daily care plan. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024g). Medication safety. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024h). Communication and Alzheimer’s. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Association. (2024i). 10 early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s. https://www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s New Zealand. (2024). What happens in the later stages of dementia. https://alzheimers.org

Alzheimer’s Society. (2024a). Why spotting the early signs of dementia is so important. https://www.alzheimers.org

Alzheimer’s Society. (2024b). Understanding and supporting a person with dementia. https://www.alzheimers.org

American Silver Alert Coalition (ASAC). (2021). What is Silver Alert? https://silveralertbill.com

Dementia Care Central. (2024). Mini-mental state exam (MMSE) Alzheimer’s / dementia test: Administration, accuracy and scoring. https://www.dementiacarecentral.com

Dementia Care Central. (2023). Balance problems associated with Alzheimer’s & dementia: Causes & solutions. https://www.dementiacarecentral.com

Dementia Care Notes. (2024). Help with activities of daily living. https://dementiacarenotes.in/caregivers/toolkit/adl/

Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA). (2024a). Dementia and driving. https://www.ca

Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA). (2024b). Caregiver’s guide to understanding dementia behaviors. https://www.ca

Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA). (2024c). Caregiver health. https://www.ca

Hamilton J. (2024). New blood tests can help diagnose Alzheimer's. Are doctors ready for what's next? https://www.npr.org

Jiao B, Rihui L, Zhou H, et al. (2023). Neural biomarker diagnosis and prediction to mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease using EEG technology. Az Res Therapy, 15, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01181-1

Mayo Clinic. (2024). Diagnosing Alzheimer’s: How Alzheimer’s is diagnosed. https://www.mayoclinic.org

Oregon Pain Guidance (OPG). (2024). Pain control in the elderly and individuals with dementia. https://www.oregonpainguidance.org

Physiopedia. (2024). Activities of daily living. https://www.physio-pedia.com

Piedmont Healthcare. (2024). Dementia caregivers guide. https://www.piedmont.org

Press D & Buss S. (2024). Treatment of Alzheimer disease. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Rosenzweig A. (2024). Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test for dementia. VeryWellHealth. https://www.verywellhealth.com

Stanford Medicine. (2024). Laboratory tests for dementia. https://stanfordhealthcare.org

Taffet G. (2023). Normal aging. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). (2024a). Amyloid PET scan for Alzheimer’s disease assessment. https://radiology.ucsf.edu

University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). (2024b). Behavior and personality changes. https://memory.ucsf.edu

University of California San Francisco (UCSF). (2024c). Dementia information: Behavior. https://memory.ucsf.edu

Van Dyke D & Dono L. (2023). 50 tips to help keep dementia and Alzheimer's patients safe in your home. https://www.aarp.org

Customer Rating

4.9 / 864 ratings