Bloodborne Pathogens Training

OSHA's Bloodborne Pathogens Standard

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

This course covers the annual requirements for bloodborne pathogens training as outlined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) of the U.S. Department of Labor, OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1030. BBP continuing education course for nursing and other healthcare professionals. Covers the four (4) basic requirements of OSHA's bloodborne pathogens standards and precautions. Includes 2023 CDC recommendations on information on transmission and protection; HBV, HCV, and HIV; personal protective equipment (PPE) and procedures.

Course Price: $18.00

Contact Hours: 2

Course updated on

November 2, 2023

"Very good! I'm saving the course materials as a reference." - Maureen, RN in California

"Wild Iris Medical Education courses have been the best distance CEU courses I have ever taken. They are informative, clear, and concise. Your website is also set up very well. Thank you!" - Eunice, RN in Minnesota

"This was an excellent review course that was presented very well." - John, RN in California

"Excellent review of OSHA/BBP." - Ron, PT in Georgia

Bloodborne Pathogens Training

OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard

Copyright © 2023 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will have the knowledge to comply with OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard and CDC directives regarding risks and precautions associated with exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- State the OSHA definition for blood and other potentially infectious materials (OPIM).

- Summarize the employer requirements of OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard.

- Describe the chain of infection as it applies to bloodborne diseases.

- Identify bloodborne diseases of concern to healthcare providers in the United States.

- Discuss how Standard Precautions protect against bloodborne pathogens.

- Discuss types of personal protective equipment, work practices, and engineering controls that reduce risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens.

- Summarize employer and employee actions to be taken in case of an occupational exposure to a bloodborne pathogen.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Bloodborne pathogens are microorganisms that may be present in human blood and can cause disease. There are a number of bloodborne pathogens, and those of primary concern are the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Exposure to blood and other body fluids that may contain blood occurs in the general population as well as in a wide variety of occupations that include healthcare workers, emergency response and public safety personnel, those working in maintenance, and those working in the waste handling industry. Individuals in these occupations can be exposed to blood through needlestick and other sharps injuries as well as through contacts with mucous membranes and skin.

Recognizing the risk for those working in these occupations has resulted in efforts to ensure their safety in the workplace, and guidance is contained in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens is often preventable.

Exposure Incidence

The U.S. Exposure Prevention Information Network (EPINet) Sharps Injury and Blood and Body Fluid Exposure Surveillance Research Group collects data annually from healthcare facilities around the United States. Participating hospitals vary in size, geographic location, and teaching status. The exposure patterns, however, are very similar, suggesting a high degree of standardization among medical devices and procedures.

In 2022 there were a total of 1,575 needlestick and sharp object injury records reviewed. Of this total:

- Nurses incurred 40.6% of exposures, followed by 17.2% among attending physicians.

- The greatest percentage of exposures (40.4%) occurred in the operating and recovery rooms, and 26.5% occurred in patient rooms or wards.

- A contaminated sharp object was involved in 1,450 injuries, with 25.4% occurring while giving an intramuscular or subcutaneous injection and 27.6% while suturing.

- The percentage of medical devices involved in injury that did not include a “safety design” was 62.6%.

- “Safety design” needles or medical devices were not activated in 66.0% of injuries and were partially activated in 26.3%.

In that same year, there were 514 blood and body fluid exposure records reviewed. Of this total:

- Nurses incurred 57.6% of exposures.

- The greatest percentage of exposures (39.4%) occurred in patient rooms or wards.

- The majority of exposures were to blood or blood products (54.2%).

- The barrier most commonly worn was a surgical mask (74.9%).

- The largest area of exposure was the face/head (81.8%).

- The greatest percentage of exposures (74.6%) was to the eyes (conjunctivae).

(ISC, 2022)

OSHA BLOODBORNE PATHOGENS STANDARD

[Content in this section of the course is taken from the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (OSHA, 2019).]

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Labor, first published the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens Standard in 1991 in Title 29 of the Code of Federal Regulations 1910.1030. In 2001, in response to the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act, OSHA revised the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard.

The Bloodborne Pathogens Standard continues to be updated regularly, with the most recent update from May 2019 (see “Resources” at the end of this course). The Standard details what employers must do to protect workers whose jobs put them at risk for exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials (OPIM). OSHA regularly inspects healthcare agencies for compliance and may fine employers if infractions are identified.

In general, OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard requires employers to:

- Provide information and training to employees that covers all elements of the Standard, including, but not limited to, information on bloodborne pathogens and diseases, methods used to control occupational exposure, hepatitis B vaccine, and medical evaluation and postexposure follow-up procedures

- Offer this training on initial assignment, at least annually thereafter, and when new or modified tasks or procedures affect a worker’s occupational exposure

Following is a description of specific elements of the Standard, but this list is not comprehensive. (See “Resources” below for a link to the full Standard.)

BLOOD AND OTHER POTENTIALLY INFECTIOUS MATERIALS

All occupational exposures to blood or other potentially infectious materials place workers at risk for infection with bloodborne pathogens.

OSHA defines blood as:

- Human blood

- Human blood components

- Products made from human blood

Other potentially infectious materials (OPIM) include:

- Semen

- Vaginal secretions

- Cerebrospinal fluid

- Synovial fluid

- Pleural fluid

- Pericardial fluid

- Peritoneal fluid

- Amniotic fluid

- Saliva in dental procedures

- Any body fluid that is visibly contaminated with blood

- All body fluids in situations where it is difficult or impossible to differentiate between them

- Any unfixed tissue or organ (other than intact skin) from a human (living or dead)

- HIV-containing cell or tissue cultures, organ cultures, and HIV- or HBV-containing culture medium or other solutions

- Blood, organs, or other tissues from experimental animals infected with HBV or HIV

Occupational exposure to human breast milk has not been shown to lead to transmission of bloodborne pathogens. However, it has been implicated in transmitting HIV from mother to infant. Therefore, gloves may be worn as a precaution by healthcare workers who are frequently exposed to breast milk.

(OSHA, 2019; CDC, 2022a)

Exposure Control Plan

Each employer having employees with occupational exposure shall establish a written exposure control plan outlining processes and procedures to prevent and correct exposure of potential infectious diseases and to provide employee training.

- Prepare an exposure determination that includes the names, department, and task of each employee where the potential for occupational exposure to body fluids exists.

- Ensure a copy of the exposure control plan is accessible to employees.

- Review and update the exposure control plan at least annually and whenever necessary to reflect new or modified tasks and procedures that affect occupational exposure and to reflect new or revised employee positions with occupation exposure. The review and update shall also:

- Reflect changes in technology that eliminate or reduce exposure to bloodborne pathogens

- Document annually consideration and implementation of appropriate commercially available and effective safer medical devices

- Document that they have solicited input from frontline workers in identifying, evaluating, and selecting effective engineering and work practice controls

Universal Precautions

- Universal precautions shall be observed to prevent contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials. Under circumstances in which differentiation between body fluid types is difficult or impossible, all body fluids shall be considered potentially infectious materials.

Engineering and Work Practice Controls

- Engineering and work practice controls shall be used to eliminate or minimize employee exposure. Where exposure remains after institution of these controls, personal protective equipment shall also be used. (See also “Personal Protective Equipment” below.)

- Engineering controls shall be examined and maintained or replaced on a regular schedule to ensure their effectiveness.

ENGINEERING CONTROL DEVICE EXAMPLES

Retractable needle.

Self-resheathing needle.

Resheathing disposable scalpel.

Phlebotomy needle with hinged shield as an add-on safety feature.

(OSHA, 2020)

- Employers shall provide handwashing facilities that are readily accessible to employees.

- When provision of handwashing facilities is not feasible, the employer shall provide either an appropriate antiseptic hand cleanser in conjunction with a clean cloth or paper towels or antiseptic towelettes. When antiseptic hand cleansers or towelettes are used, hands shall be washed with soap and running water as soon as feasible.

- Employers should ensure that employees wash their hands immediately or as soon as feasible after removal of gloves or other personal protective equipment.

- Employers shall ensure employees wash hands and skin with soap and water or flush mucous membranes with water immediately or as soon as feasible following contact with blood or OPIM. (See also “Hand Hygiene” later in this course.)

- Contaminated needles and other contaminated sharps shall not be bent, recapped, or removed unless the employer can demonstrate that no alternative is feasible or that such action is required by a specific medical or dental procedure. Such bending, recapping, or needle removal must be accomplished through the use of a mechanical device or a one-handed technique. Shearing or breaking of contaminated needles is prohibited. (See also “Sharps Handling” later in this course.)

- Immediately or as soon as possible after use, contaminated reusable sharps shall be placed in appropriate containers until properly reprocessed.

- Employers must prohibit eating, drinking, smoking, applying cosmetics or lip balm, and handling contact lenses in work areas where there is a reasonable likelihood of occupational exposure.

- Food and drink shall not be kept in refrigerators, freezers, shelves, cabinets, or on countertops or benchtops where blood or OPIM are present.

- All procedures involving blood or OPIM shall be performed in such a manner as to minimize splashing, spraying, spattering, and generation of droplets of these substances.

- Mouth piping or suctioning of blood or OPIM is prohibited.

- Specimens of blood or OPIM shall be placed in a container that prevents leakage during collection, handling, processing, storage, transport, or shipping.

- Equipment that may become contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials shall be examined prior to servicing or shipping and shall be decontaminated as necessary, unless the employer can demonstrate that decontamination of such equipment or portions of such equipment is not feasible.

Personal Protective Equipment

- Employers shall provide at no cost to the employee personal protective equipment (PPE), such as, but not limited to, gloves, gowns, laboratory coats, face shields or masks and eye protection, mouthpieces, resuscitation bags, pocket masks, or other ventilation devices.

- Employers shall ensure that appropriate personal protective equipment in the appropriate sizes is readily accessible at the worksite or is issued to employees. Hypoallergenic gloves, glove liners, powderless gloves, or other similar alternatives shall be readily accessible to those who are allergic to the gloves normally provided.

- Employers must clean, repair, and replace this equipment as needed. Provision, maintenance, repair, and replacement are at no cost to the employee.

- Garments penetrated by blood or other potentially infectious materials shall be removed immediately or as soon as feasible.

- All personal protective equipment shall be removed prior to leaving the work area; when personal protective equipment is removed it shall be placed in an appropriately designated area or container for storage, washing, decontamination, or disposal.

(See also “Standard Precautions, Personal Protective Equipment” later in this course.)

Housekeeping and Regulated Waste Disposal

- Employers shall ensure the worksite is maintained in a clean and sanitary condition. The employer shall determine and implement an appropriate written schedule for cleaning and method of decontamination based upon the location within the facility, type of surface to be cleaned, type of soil present, and tasks or procedures being performed in the area.

- Contaminated sharps shall be discarded immediately or as soon as feasible in containers that are closeable, puncture resistant, leakproof, and labeled or color-coded.

- Employers must ensure that employees who have contact with contaminated laundry wear protective gloves and other appropriate personal protective equipment.

HIV, HBV, and Vaccination and Postexposure Requirements

- HIV and HBV laboratory and production facility workers must receive specialized initial training in addition to the training provided to all workers with occupational exposure risks.

- Hepatitis B vaccination must be offered after the worker has received the required bloodborne pathogens training and within 10 days of initial assignment to a job with occupational exposure.

- Employers shall make available hepatitis B vaccinations to all workers with occupational exposure and post-exposure evaluation and follow-up to all employees who have had an exposure incident. (See also “Postexposure Measures and Follow-Up” later in this course.)

- The healthcare professional will provide a limited written opinion to the employer, and all diagnoses must remain confidential.

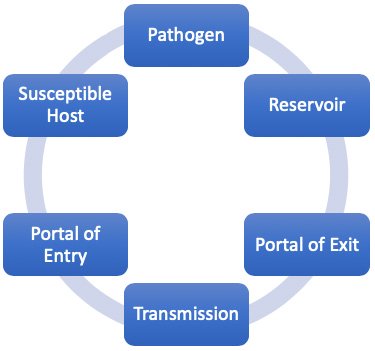

CHAIN OF INFECTION

Epidemiology involves knowing how disease spreads and how it can be controlled. Infection can only spread when conditions are right. This set of conditions is referred to as the chain of infection, which consists of six links. When all the links are connected, infection spreads (APIC, 2023).

Chain of infection.

(Source: Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.)

- Infectious organisms can be bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites.

- A reservoir of an infectious agent is the habitat where the agent normally lives and grows. Reservoirs may be dirty surfaces and equipment, humans, animals and insects, or soil. In the case of bloodborne infectious diseases, humans are generally the reservoirs.

- The portal of exit is the path by which the infectious agent leaves its host. This can occur through open wounds or skin, the splatter of body fluids, aerosols, or needle or other sharps contamination.

- Means of transmission is the mode by which the infectious agent is transmitted from its natural reservoir to a susceptible host. Transmission can occur by a mode that is direct (e.g., OPIM exposure from the reservoir patient directly to exposed nonintact skin or mucous membrane of the host) or indirect (e.g., needlestick).

- The portal of entry refers to the way in which the infectious agent enters the host. The portal of entry must provide access to tissues in a way that allows the infectious agent to multiply and thrive. Portal of entry for bloodborne pathogens can include broken or punctured skin, incisions, mucous membranes, and across the placenta to fetus.

- The final link is the vulnerable host. Susceptibility of a host depends on many factors, including immunity and the individual’s ability to resist infection.

(APIC, 2023)

By breaking any link of the chain of infection, healthcare professionals can prevent the occurrence of new infection. Infection prevention measures are designed to break the links and thereby prevent new infections. The chain of infection is the foundation of infection prevention.

PATHOGENS

Bloodborne pathogens are microorganisms present in human blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM) that can cause disease in humans. Many are relatively rare, but of those bloodborne pathogens known to cause diseases, there are three diseases specifically addressed by the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard that are the most common pathogens of concern in the work place—hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses, which cause inflammation of the liver, and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). These three account for the majority of occupationally acquired infections associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Denault & Garner, 2023).

OTHER BLOODBORNE PATHOGENS

- Malaria

- Syphilis

- Hepatitis D

- Hepatitis E

- Hepatitis G

- Human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV)

- Brucellosis

- Babesiosis

- Ehrlichiosis

- Chagas disease

- Lechmaniasis

- Leptospirosis

- Relapsing fever

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- Viral hemorrhagic fever

- West Nile virus

- Ebola (also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever)

- Zika viral infection

(CDC, 2022d; MNDH, 2022)

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Hepatitis B is an infection of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus. Acute hepatitis is a short-term illness that occurs within the first six months following exposure. Some people with acute hepatitis B have no symptoms at all or only a mild illness. For others, acute hepatitis causes more severe illness and requires hospitalization.

Approximately 25% of those who become chronically infected by HBV during childhood and 15% of those after childhood die prematurely from cirrhosis or liver cancer, and most remain asymptomatic until onset of cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease.

In 2020, a total of 2,157 cases of acute hepatitis B were reported to the CDC, for an overall incidence rate of 0.7 per 100,000 population. After adjusting for under-reporting by healthcare providers and under-ascertainment (those not seeking healthcare), there are an estimated 580,000 to 1.17 million people with HBV infection in the United States, two thirds of whom may be unaware of their infection. During that same year, a total of 1,752 hepatitis-B-associated deaths among U.S. residents were reported, corresponding to a death rate of 0.45 cases per 100,000 population (CDC, 2023a).

TRANSMISSION

HBV is transmitted through activities that involve percutaneous or mucosal contact with infectious blood or body fluids (e.g., semen or saliva), including:

- Sex with an infected partner

- Injection drug use that involves sharing needles, syringes, or drug-preparation equipment

- Mother-to-baby during pregnancy or delivery

- Contact with blood or open sores of an infected person

- Needlesticks or sharp instrument exposures

- Sharing items that can break the skin or mucous membranes (such as razors, toothbrushes, or medical equipment [e.g., glucose monitor]) with an infected person

- Poor infection control practices in healthcare settings

HBV is not transmitted through:

- Breastfeeding

- Sharing eating utensils

- Hugging, kissing, holding hands

- Coughing or sneezing

- Contaminated food or water (unlike some other forms of hepatitis)

HBV is very resilient and can survive outside the body at least seven days and still be capable of causing infection. For this reason, the virus is a concern for medical personnel such as nurses, laboratory technicians, and paramedics, as well as custodians, laundry personnel, and other employees who may come in contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials (CDC, 2023a).

HEPATITIS B VACCINE

The hepatitis B vaccine is the best protection from the disease. All employees who may possibly be exposed to blood or other potentially infectious materials as part of their job duties are eligible to be vaccinated against HBV.

As described above, the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogens Standard 1910.1030(f)(1)(i) states that employers shall make available the hepatitis B vaccine and vaccination series to all employees who have occupational exposure and postexposure evaluation and follow-up to all employees who have had a recent exposure incident. The vaccine and vaccination must be offered at no cost to the employee and at a reasonable time and place (OSHA, 2019).

Hepatitis B vaccines available in the United States include:

- Engerix-B

- Recombivax HB

- Heplisav-B

- Prehevbrio (13)

Three intramuscular injections are required for the first three vaccines at one and six months after the first dose. Heplisav-B, however, is approved for two doses, one month apart.

To ensure immunity, it is important to receive all recommended injections. The vaccine causes no harm to those who are already immune or to those who may be HBV carriers.

Although employees may opt to have their blood tested for antibodies to determine the need for the vaccine, their employers may not make such screening a condition of receiving vaccination, nor are employers required to provide screening.

Employees who decide to decline vaccination must complete a mandatory declination form, the purpose being to encourage greater participation in the vaccination program by stating that the worker declining the vaccination remains at risk of acquiring hepatitis B. An employee may opt to take the vaccine at any time even after initially declining it (OSHA, 2019; CDC, 2023a).

POSTEXPOSURE MANAGEMENT

Following an exposure to HBV, prophylaxis can prevent HBV infection and subsequent development of chronic liver infection. The central component of postexposure prophylaxis is hepatitis B vaccine, which provides long-term protection. The vaccine series should be started as soon as possible after exposure, preferably within 24 hours. In certain circumstances, hepatitis B immune globulin is recommended in addition to vaccine to provide short-term passive immunity (CDC, 2020a).

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

HCV is a serious infection of the liver caused by the bloodborne hepatitis C virus. For some people, hepatitis C is a short-term illness, but for more than 50% of those who become infected, it becomes a long-term, chronic infection that can result in serious, even life-threatening, health problems such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. Approximately 5%–25% of people with chronic hepatitis C develop cirrhosis over 10 to 20 years. People with chronic hepatitis C may have no symptoms, but when symptoms do appear, they are often a sign of advanced liver disease. People with hepatitis C and cirrhosis have a 1%–4% annual risk for hepatocellular carcinoma.

In 2020 there were an estimated 66l,700 reported cases of hepatitis C infection in the United States, and 41 states reported a total of 107,300 newly identified chronic hepatitis C cases and 40.7 newly reported cases of chronic hepatitis C per 100,000 people. The incidence rate of acute hepatitis C has more than doubled since 2013 and increased 15% from 2019, primarily resulting from the ongoing opioid epidemic and associated injection drug use.

Because the hepatitis C virus has multiple genotypes and subtypes and mutates rapidly, there is no vaccine (CDC, 2023a; Spach, 2021).

TRANSMISSION

HCV transmission occurs mainly through parenteral exposures to infectious blood or body fluids that contain blood. Mucous membrane exposures to blood can also result in transmission, although less efficiently. HCV is transmitted primarily through sharing contaminated needles, syringes, or other equipment used to inject drugs.

HCV is less commonly transmitted through:

- Birth to an infected pregnant person

- Sexual contact with an infected person

- Unregulated tattooing or piercing

- Needlesticks or other sharp instrument injuries

(CDC, 2023a)

POSTEXPOSURE MANAGEMENT

The risk of HCV transmission after percutaneous exposure is approximately 0.2% when the source patient is HCV infected. Following exposure, initial management includes baseline testing of the source patient and the healthcare worker as soon as possible (preferably within 48 hours) after exposure, with initial follow-up in six weeks and final follow-up in 4–6 months.

Testing for HCV is based on the following sequence: Most persons who acquire HCV infection will have a positive HCV RNA within 1–2 weeks of exposure, and antibodies to HCV generally appear 8–11 weeks after exposure.

If the source patient is HCV-RNA-positive or source-patient testing is not performed or not available, baseline testing should be followed by a nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA at 3–6 weeks post exposure This test also should be performed if a source patient is anti-HCV-positive and no source patient HCV RNA is available.

Postexposure therapy with direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) is not routinely recommended, as percutaneous and mucocutaneous exposure risks are low and in most situations do not justify giving these medications because of potential side effects.

Healthcare personnel with detectable HCV RNA or anti-HCV seroconversion as a result of an occupational exposure should be referred for further care and evaluation for treatment. DAA therapy is highly efficacious, and new HCV infections should be identified early and treated (CDC, 2023a; NCCC, 2021).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

HIV has existed in the United States since at least the mid- to late-1970s. The virus spreads via blood and other body fluids and attacks the body’s immune system, specifically the CD4+ T cells. Untreated HIV infection reduces the number of T cells in the body, which makes it more and more difficult for the body to fight off infections and other diseases. There currently is no effective cure for HIV infection, and once an individual becomes infected, they are infected for life. Opportunistic infections or cancers take advantage of a very weak immune system and are signs that a person has AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

In 2021, 36,136 people received an HIV diagnosis in the United States and dependent areas. The annual number of new diagnoses decreased 7% from 2017 to 2021, and at that time, there were an estimated 1.2 million people in the United States living with HIV. Of these people, 87% knew they were infected (CDC, 2022b).

TRANSMISSION

HIV is transmitted most commonly in the United States through sexual behaviors and sharing of needles, syringes, or equipment used to prepare drugs for injection. Only certain body fluids (blood, semen, preseminal fluid, rectal fluids, vaginal fluids, and breast milk) from a person who is infected can transmit HIV. These fluids must come in contact with a mucous membrane or damaged tissue or be directly injected into the bloodstream for transmission to occur.

For healthcare workers, the risk of occupational exposure is very low. The main risk is from being stuck with an HIV-contaminated needle or other sharp object. This risk, however, is small and estimated to be less than 1%. HIV contamination has also been reported by healthcare workers from body fluid splashes to the eye, the risk of which is near zero.

There is no vaccine to prevent HIV infection, but HIV prevention medications such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) are available. The best way for healthcare workers to protect against infection is by strict adherence to Standard Precautions (CDC, 2022b).

POSTEXPOSURE MANAGEMENT

Occupational exposures require urgent medical evaluation. Baseline HIV testing of the source patient and the exposed worker should be done as soon as possible.

PEP should be initiated as soon as possible within a maximum of 72 hours after a recent possible exposure to HIV, but the earlier PEP is started, the better. If additional information subsequently becomes available that the source person is HIV negative, PEP can always be discontinued.

Three-drug PEP regimens are now the recommended management for all exposures. There are some special circumstances in which a two-drug regimen can be considered or used, especially when recommended antiretroviral medications are unavailable or there is a concern about potential toxicity or adherence difficulties.

The preferred three-drug HIV PEP regimen includes Truvada, which is a two-drug combination of emtricitabine (FTC) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, one tablet orally once daily, plus either raltegravir (Isentress) 400 mg orally twice daily or dolutegravir (Dovato) 50 mg orally once daily. This regimen is continued for a 28-day duration.

If the source person tests negative for HIV, PEP is discontinued, and no follow-up HIV testing is clinically indicated for the exposed worker. If the source person tests positive, the exposed worker is retested for HIV at six weeks and three months (NCCC, 2021).

EXPOSURE PREVENTION

It is important for all healthcare workers to understand the role they play in protecting themselves, coworkers, patients, and families from exposure to bloodborne pathogens. The employer’s exposure control plan provides the following detailed information about how each healthcare worker can take appropriate steps to reduce or eliminate the risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens as well as other infectious agents.

Universal and Standard Precautions

Universal Precautions is the term used to describe a prevention strategy in which all blood and OPIM are treated as if they are actually infectious, regardless of the perceived status of the source individual. In other words, whether or not one thinks the blood or body fluid is infected with bloodborne pathogens, treat it as if it is. This approach is used in all situations where exposure to blood or OPIM is possible. In addition, certain engineering and work practice controls are always utilized in situations where exposure may occur.

OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard allows for healthcare facilities to use acceptable alternatives to Universal Precautions. The CDC revised the infection control practice from Universal Precautions to Standard Precautions in 1996. Standard Precautions combine the major features of Universal Precautions with body substance isolation (BSI). Standard Precautions incorporate not only the fluids and materials covered by the Bloodborne Pathogens Standard but expand coverage to include any and all body fluids and substances (OSHA, 2019).

These precautions are intended to address all modes of transmission by any type of organism. Routes of transmission may be direct or indirect.

- Direct transmission is the immediate transfer of microorganisms from one infected person to another without a contaminated intermediate object or person, including:

- Direct contact, such as skin to skin

- Direct projection of a spray of droplets, such as coughing, sneezing, speaking, or spitting onto a close contact

- Inoculation into skin or mucosa, such as through contaminated needles

- Indirect transmission includes a variety of mechanisms and requires that the infectious agent is capable of surviving outside the host in the external environment:

- Vehicle borne, such as through water, food, ice, blood, plasma, and other biological products

- Vector borne, such as by an arthropod or any living carrier

- Airborne by evaporation of droplets that are coughed or sneezed into the air or generated purposefully by atomizing devices and disseminated by air currents and that can remain suspended in air for hours or settle and become part of dust

- Fomite (inanimate articles or substances) borne, such as clothing, utensils, and furniture that are contaminated by infectious substances and capable of harboring and transferring the agent

Standard Precautions for Bloodborne Pathogens

The Standard Precautions that are to be followed by all healthcare workers when concerned with bloodborne pathogens or other potentially infectious materials include:

- Performing hand hygiene

- Using personal protective equipment (PPE) whenever there is an expectation of possible exposure to infectious material

- Following respiratory hygiene or cough etiquette principles

- Ensuring appropriate patient placement

- Properly handling and properly cleaning and disinfecting patient-care equipment and instruments or devices; appropriate cleaning and disinfecting of the environment

- Handling textiles and laundry carefully

- Safe injection practices

- Infection control practices for special lumbar procedures

- Ensuring healthcare safety by proper handling of regulated waste, including proper handling of needles and other sharps

(CDC, 2023b)

HAND HYGIENE

Hand hygiene involves cleaning hands with soap and water, antiseptic hand wash, antiseptic hand rub, or surgical hand antisepsis. Hands should be washed with soap and water whenever they are visibly dirty, before eating, and after using the restroom. Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are the preferred method for cleaning hands in most clinical situations.

Using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer or handwashing with soap and water is to be performed:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- After contact with blood, body fluids or excretions, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or wound dressings

- After contact with a patient’s intact skin

- If hands will be moving from a contaminated body site to a clean body site

- After contact with inanimate objects in the immediate vicinity of the patient

- When hands are visibly soiled

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive medical devices

- After caring for a person with known or suspected infectious diarrhea

- Immediately after glove removal

(CDC, 2023b)

Recommendations regarding fingernails state:

- Do not wear artificial fingernails or extenders if duties include direct contact with patients at high risk for infection and associated adverse outcomes (e.g., those in ICUs or ORs).

- Keep natural nail tips less than 1/4-inch long.

(CDC, 2023b)

HAND HYGIENE WITH SOAP AND WATER OR HAND SANITIZER

The CDC guidelines for hand hygiene in healthcare settings recommend:

When using soap and water:

- Wet hands with clean running water (warm or cold), turn off the tap, and apply soap.

- Lather hands by rubbing them together. Lather the back of the hands, between fingers, and under nails.

- Scrub hands for at least 20 seconds.

- Turn on the tap with elbow or disposable towel.

- Rinse hands well under clean running water.

- Dry hands using a disposable towel or air dryer.

- Use a clean disposable towel to turn off the faucet.

When using an alcohol-based hand sanitizer:

- Apply the amount of product recommended by the manufacturer to the palm of one hand.

- Cover all surfaces of hands.

- Rub the product over all the surfaces of the hands and fingers until hands are dry; this should take about 20 seconds.

(CDC, 2022c)

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE)

To protect oneself, healthcare providers must have a protective barrier between them and any potentially infectious material. Personal protective equipment is defined by OSHA as specialized clothing or equipment worn by a healthcare worker for protection against infectious materials.

Employers are required to provide and maintain clean, appropriate PPE at no cost to employees. Latex-free PPE must be made available on request. PPE must be readily accessible to employees and available in appropriate sizes. It is important to know which type of PPE is available at work and where it is stored.

Types of PPE used in healthcare settings to protect healthcare workers from exposure to bloodborne pathogens include:

- Gloves

- Gowns, aprons, coveralls, laboratory coats

- Masks, face shields, goggles

- Ventilation devices (mouthpieces, pocket masks, resuscitation devices)

- Head coverings

- Boots or shoe covers

- Respirators

Factors that influence the selection of appropriate PPE include:

- Type of exposure anticipated

- Splash or spray versus touch

- Category of isolation precautions (Contact, Droplet, Airborne)

- Durability and appropriateness for the task

- Fit of the equipment

Gloves

Gloves are the most common type of PPE and are not a substitute for hand hygiene. They are used for patient care as well as when contacting environmental services. Gloves can be sterile or nonsterile and single-use or reusable. Because of allergy concerns, latex products have been eliminated in many facilities, and materials used for gloves are mostly synthetics such as vinyl or nitrile.

- Wear gloves when reasonably anticipated that contact with blood or OPIM, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or potentially contaminated intact skin could occur.

- Wear gloves with fit and durability appropriate to the task.

- Wear disposable medical examination gloves for direct patient care.

- Wear disposable medical examination gloves or reusable utility gloves for cleaning environment or medical equipment.

- Remove gloves after contact with a patient or the surrounding environment (including medical equipment) using proper technique to prevent hand contamination.

- Never wear the same pair of gloves for the care of more than one patient.

- Never wash patient-care gloves for reuse.

- Change gloves during patient care if hands will move from a contaminated body site to a clean body site.

(CDC, 2023b)

Gowns

Gowns appropriate to the task are worn to protect skin and prevent soiling or contamination of clothing during procedures and patient-care activities when contact with blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions is anticipated.

- Wear a gown for direct patient contact if the patient has uncontained secretions or excretions.

- Remove a gown and perform hand hygiene before leaving the patient’s environment.

- Do not reuse gowns, even for repeated contacts with the same patient.

Routine donning of gowns upon entrance into a high-risk unit (e.g., ICU, NICU, HSCT unit) is not indicated (CDC, 2023b).

Mouth, Nose, and Eye Protection

Face and eye protection, including masks, goggles, face shields, and combinations of each, are selected according to the needs anticipated by the task to be performed to protect the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and mouth during procedures and patient-care activities that are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood, body fluids, secretions, and excretions.

During aerosol-generating procedures in patients who are not suspected of being infected with an agent for which respiratory protection is otherwise recommended (e.g., tuberculosis), wear one of the following in addition to gloves and gown:

- A face shield that fully covers the front and sides of the face

- A mask with attached shield

- Mask and goggles

(CDC, 2023b)

Head Coverings

Head coverings such as surgical caps are worn when gross contamination is expected, such as during orthopedic surgery or autopsies (OSHA, 2019).

Boots or Shoe Covers

Theater boots are waterproof boots worn by surgical personnel as a protective measure from contamination with blood and other body fluids. Shoe covers protect the wearer from accidental spills and body fluids (OSHA, 2019).

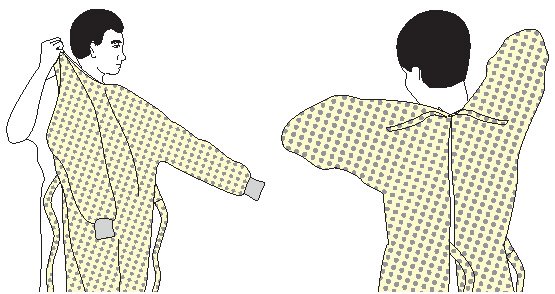

DONNING PPE

There are various ways to don PPE. The CDC recommends that PPE be put on in the following sequence:

- Gown

- Mask

- Face shield or goggles

- Gloves

How to put on a gown:

- Perform hand hygiene using hand sanitizer.

- Select appropriate type and size.

- Put on with opening in the back.

- Secure at neck and waist.

- If gown is too small, use two gowns, with the first tied in front and the second tied in back.

How to put on a mask:

- Place over nose, mouth, and chin.

- Fit flexible nose piece over bridge of nose using both hands.

- Ensure facemask extends under the chin.

- Secure on crown of the head and base of the neck. If mask has loops, hook them around the ears.

How to put on goggles and face shield:

- Place over face and eyes.

- Adjust to fit.

How to put on gloves:

- Select correct type and size.

- Insert hands into gloves.

- Extend gloves over isolation gown cuffs.

(CDC, 2020b)

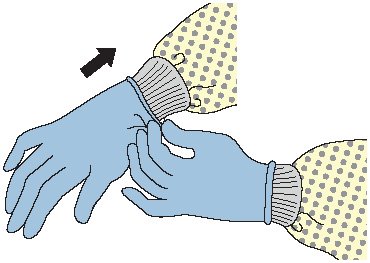

DOFFING PPE

More than one doffing method may be acceptable. Training and practice using the healthcare facility’s procedure is critical. One example of removing PPE is described below.

Remove contaminated PPE in the following sequence:

- Gloves

- Gown

- Face shield or goggles

- Mask or respirator

PPE is to be removed at the doorway before leaving the patient room or in the anteroom. Respirators are removed outside the room after the door has been closed.

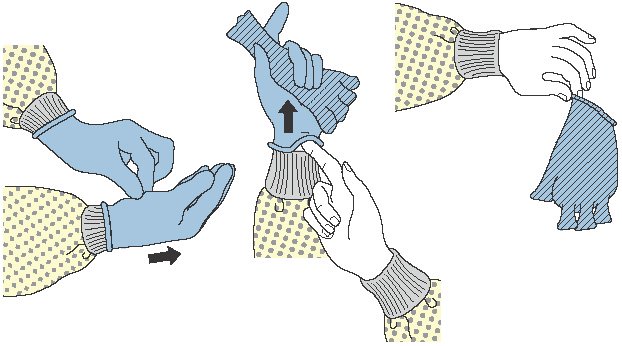

How to remove gloves:

- Grasp outside edge near wrist.

- Peel away from hand, turning glove inside out.

- Hold in opposite gloved hand.

- Slide ungloved finger under wrist of remaining glove.

- Peel off from inside, creating a bag for both gloves.

- Discard.

- Perform hand hygiene if contamination occurs during glove removal.

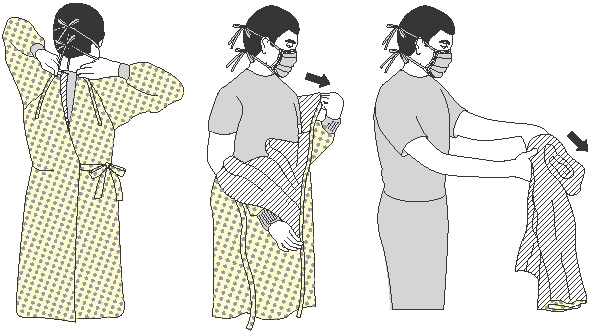

How to remove gown:

- Consider gown front and sleeves to be contaminated.

- Unfasten ties. (Some gown ties can be broken rather than untied.)

- Pull gown away from neck and shoulders, touching inside of gown only.

- Turn contaminated outside toward the inside and over the hands.

- Fold or roll into a bundle and discard.

- Perform hand hygiene if contamination occurs.

How to remove goggles or face shield:

- Consider outside of goggles or face shield to be contaminated.

- Remove from the back by lifting head band or ear pieces.

- Lift away from face.

- Place in the designated receptacle for reprocessing or disposal.

- Perform hand hygiene if contamination occurs.

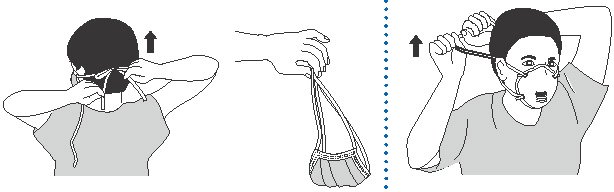

How to remove mask:

- Consider the front of the mask to be contaminated; do not touch.

- Carefully untie bottom ties, then upper ties, or unhook from ears and pull away from face.

- Discard.

- Perform hand hygiene before exiting the patient area.

(CDC, 2020b)

CLEANING AND DISINFECTING

All equipment and environmental and working surfaces must be cleaned and decontaminated after contact with blood or other potentially infectious material. Protective gloves and other PPE should be worn as necessary, and an appropriate disinfectant should be used.

When cleaning up a blood spill or OPIM, use protective gloves or other PPE as necessary and:

- Confine the spill and immediately wipe it up with absorbent (paper) towels, cloths, or absorbent granules that are spread over the spill to solidify the blood or body fluid. Dispose of all as infectious waste.

- Clean up all blood thoroughly using neutral detergent and warm water solution before applying the disinfectant.

- Disinfect by using a facility-approved intermediate-level disinfecting solution; typically, chlorine-based disinfectants are adequate for disinfecting spills.

- When using a diluted bleach solution, contact time is the length of time it takes for the solution to dry. (Do not use a diluted bleach solution to clean up a urine spill due to risk of chlorine gas.)

- Allow disinfectant to remain wet on the surface for the recommended contact time, then rinse the area with clean water to remove the disinfectant residue (if required).

- Immediately send all reusable supplies and equipment (e.g., cleaning cloths, mops) for reprocessing (i.e., cleaning and disinfection) after the spill is cleaned up.

Liquid chlorine bleach comes in different concentrations. To make a 0.5% chlorine solution from 3.5% bleach, use 6 parts of water per 1 part bleach (CDC, 2023c).

HANDLING CONTAMINATED LAUNDRY

Contaminated laundry (i.e., soiled with blood or OPIM or that may contain sharps) should be handled as little as possible and should not be sorted or rinsed in the location of use. Contaminated laundry is bagged at the location of use into labeled or color-coded bags or containers. Contaminated laundry that is wet is placed and transported in containers or bags that prevent soak-through or leakage (OSHA, 2019).

HANDLING REGULATED WASTE

Regulated waste refers to:

- Any liquid or semiliquid blood or other OPIM

- Contaminated items that would release blood or OPIM in a liquid or semi-liquid state if compressed

- Items that are caked with dried blood or OPIM and are capable of releasing these materials during handling

- Contaminated sharps

Regulated waste shall be placed in containers which are closable; constructed to contain all contents and prevent leakage of fluids during handling, storage, transport, or shipping; and labeled or color-coded in accordance with the OSHA Standard.

If outside contamination of the regulated waste container occurs, place it in a second container, close, and color-code or label with biohazard symbols (OSHA, 2019).

Sharps Handling

Contaminated sharps are needles, blades (such as scalpels), scissors, and other medical instruments and objects that can puncture the skin. Contaminated sharps must be properly disposed of immediately or as soon as possible into containers that are closable, puncture-resistant, leak-proof on the sides and bottom, and color-coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol.

HOW TO HANDLE SHARPS

- Discard needle or syringe units without attempting to recap the needle whenever possible.

- If a needle must be recapped, never use both hands; use the single-hand “scoop” method.

- Never break or shear needles.

- To move or pick up needles or other sharp devices, use a mechanical device or tool, such as forceps, pliers, or broom and dustpan.

- Dispose of needles in labeled sharps containers only; sharps containers must be accessible and maintained upright. When transporting sharps containers, close the containers immediately before removal or replacement to prevent spillage or protrusion of contents during handling or transport.

(OSHA, 2019)

POSTEXPOSURE MEASURES AND FOLLOW-UP

Emergency Steps Following an Accidental Exposure

If an occupational exposure to blood or other body fluids occurs, the following steps should immediately be taken:

- Wash puncture and small wounds with soap and water for 15 minutes.

- Apply direct pressure to lacerations to control bleeding, and seek medical attention.

- Flush mucous membranes with water; rinse mouth several times with water.

- If eyes were exposed:

- Remove contact lenses.

- If eye wash station is available, flush eyes for 15 minutes.

- If eye wash station is not available, have a peer flush exposed eyes with 500 ml lactated ringer’s solution or normal saline.

- If unable to do the above, flush eyes under the sink with water for 15 minutes or as tolerated. Keep eyes open and rotate the eyeballs in all directions to remove contamination.

- Seek medical care to determine risk associated with exposure.

- Report blood and body fluid exposures immediately and as soon as possible to assist obtaining a test from the source.

(CDC, 2019)

Employer Follow-Up

Following an exposure incident, the employer is required to:

- Make immediately available to the exposed employee a confidential medical evaluation and follow-up, including at least the following:

- Documentation of the route(s) of exposure and circumstances under which the exposure incident occurred

- Identification and documentation of the source individual, unless the employer can establish that identification is not possible or prohibited by state or local law

- Test the source individual’s blood as soon as possible and after consent is obtained.

- Make the results of the source persons’ testing available to the exposed employee, and inform the employee of applicable laws and regulations concerning disclosure of the identity and infectious status of the source person.

- Ensure that all medical evaluations, laboratory tests and procedures, and postexposure evaluation and follow-up, including prophylaxis, are made available at no cost and at a reasonable time and place to the employee.

- Administer postexposure prophylaxis if medically necessary, as recommended by the U.S. Public Health Service.

- Offer the healthcare worker counseling that includes recommendations for transmission and prevention of HIV.

- Make available hepatitis B vaccinations to all workers with occupational exposures and postexposure and follow-up with all employees who have an exposure incident.

(OSHA, 2019)

CONCLUSION

Protection of healthcare workers against bloodborne pathogens is of vital importance. Healthcare workers must have an understanding of how bloodborne pathogens are transmitted as well as the standards and precautions recommended to prevent exposure. Following OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, including the use of Standard Precautions, can break the chain of infection, reduce the risk of exposure, and ensure a safe working environment.

REFERENCES

NOTE: Complete URLs for references retrieved from online sources are provided in the PDF of this course.

Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC). (2023). Break the chain of infection. https://infectionpreventionandyou.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023a). Viral hepatitis. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023b). Infection control: Isolation precautions. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022a). Breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022b). HIV. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022c). Handwashing: Clean hands save lives. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (CDC). (2022d). Diseases and organisms. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Hand hygiene in healthcare settings. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020a). Postexposure prophylaxis. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020b). Using personal protective equipment (PPE). https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019). Stop sticks campaign. https://www.cdc.gov

Denault D & Garner H. (2023). OSHA bloodborne pathogen standards. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

International Safety Center (ISC). (2022). U.S. EPINet sharps injury and blood and body fluid exposure surveillance research group. Blood and body fluid exposure report for 2022. https://internationalsafetycenter.org

Kshirsagar D. (2021). Modes of transmission. https://www.slideshare.net

Minnesota Department of Health (MNDH). (2022). Bloodborne pathogens. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/bloodborne/index.html

National Clinician Consultation Center (NCCC). (2021). PEP quick guide for occupational exposures. https://nccc.ucsf.edu

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), U.S. Department of Labor. (2020). Needlestick/sharps injuries. https://www.osha.gov

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). (2019). 1910.1030 Bloodborne pathogens standard. https://www.osha.gov

Spach D. (2021). HCV epidemiology in the United States. https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu

Customer Rating

4.9 / 1003 ratings