HIV/AIDS Training and Education for Healthcare Professionals

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

3-hour continuing education course on HIV/AIDS training for nursing, occupational therapy, and other health professions. This online CEU covers HIV etiology and epidemiology, risk factors for transmission, HIV testing and counseling, clinical manifestations, antiretroviral therapy, patient care management guidelines, and preventive and control measures.

"This was so very well written and presented in such an organized, intuitive manner that I was blown away. Useful and informative, it should be a guide for future content developers." - Christine, RN in Florida

"Excellent course — relevant and concise." - Allison, RN in Florida

"Course was written in a simple way that was easy to comprehend." - Thayra, nursing student in Florida

"I'm confident after reading this course to work with any HIV patient. I also learned how to protect myself." - Yveny, RN in Florida

HIV/AIDS Training

Copyright © 2023 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this course, you will have increased your knowledge of HIV/AIDS in order to better care for your patients. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Discuss HIV and the epidemiology of HIV infection in the United States.

- Explain HIV/AIDS etiology.

- Summarize the risk factors for transmission of HIV.

- Describe HIV testing and counseling.

- Describe the clinical manifestations of HIV.

- Identify antiretroviral therapy and patient care management guidelines for HIV/AIDS.

- Summarize preventive and control measures for HIV/AIDS.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has now been with us for over four decades, and in that span of time, at least 32 million lives have been lost. The pandemic continues to expand in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa (Beyrer, 2021).

HIV/AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas Today

As of 2021 in the United States and its six dependent areas, there were more than 1.2 million people living with HIV. In 2020, 30,635 people received an HIV diagnosis—a 17% decrease from the previous year. Among 28,422 persons with HIV infection diagnosed during 2020 in the 46 jurisdictions with complete reporting of laboratory data to the CDC, viral load was suppressed in 67.8% of persons within 6 months of HIV diagnosis.

In 2020, there were 18,489 deaths among adults and adolescents diagnosed with HIV, attributable to any cause, including COVID-19.

Among those who received an HIV diagnosis during 2020, more than 1 in 5 persons (21.6%) received a late-stage diagnosis (AIDS). The highest percentages of late-stage diagnoses occurred among:

- Persons ages 55 and older (37.1%)

- Asians (27.7%)

- Females (23.2%)

The lowest percentages were among:

- Transgender men (5.0%)

- Persons ages 13–24 years (9.1%)

- Black/African Americans (20.0%)

- Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders (20.0%)

The percentage among injection drug users were:

- Females (78.1%)

- Males (77.8%)

(CDC, 2022a)

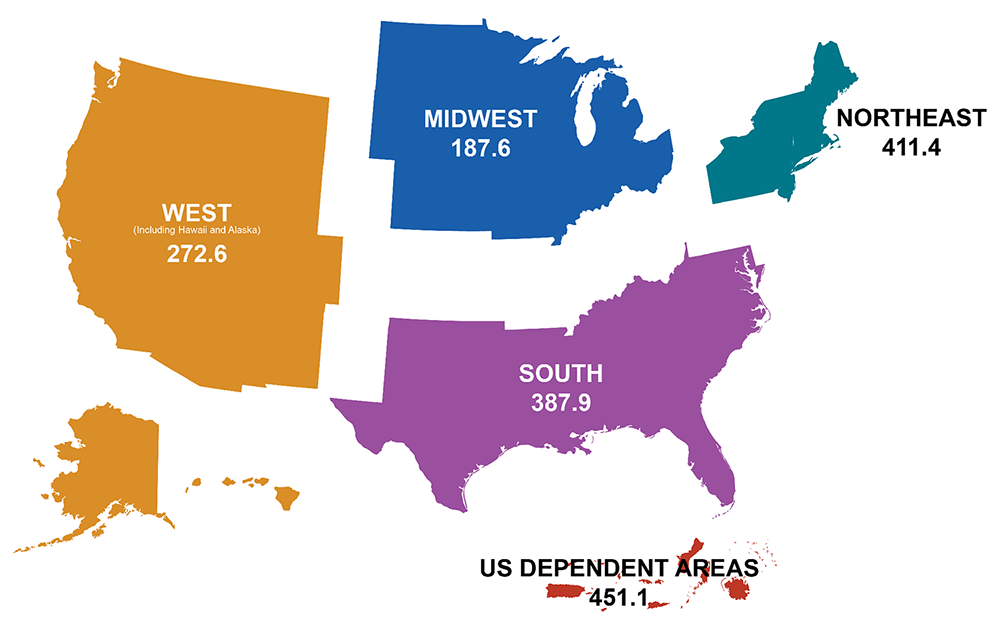

Rates of people with diagnosed HIV in the United States and dependent areas by region of residence, 2021, per 100,000 people. (Source: CDC.)

HIV/AIDS ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, spreads via certain body fluids; specifically attacks the CD4, or T cells, of the immune system; and uses those cells to make copies of itself. CD4 cells, also called helper T cells, are a class of white blood cells that help other lymphocytes (memory B cells) that are responsible for producing an antibody to fight infection based on stored data following past exposure to the antibody. As time passes, the virus can destroy enough of these specialized cells that the immune system no longer is able to fight off infections and disease.

HIV is unique among many other viruses because the body is unable to destroy it completely, even with treatment. As a result, once a person is infected with the virus, the person will have it for the remainder of their life (CDC, 2022b).

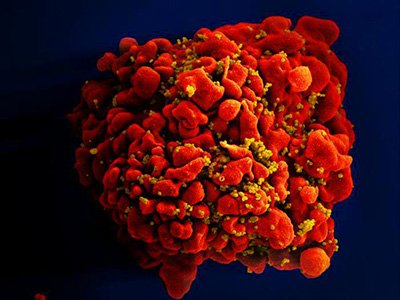

A single T cell (red) infected by numerous, spheroid shaped HIV particles (yellow). (Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2012.)

After the initial infection and without treatment, the virus continues to multiply, and over a period of time (which can be 10 years or longer), common opportunistic infections (OIs) begin to take advantage of the body’s very weak immunity. When an opportunistic infection occurs, the person has developed acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Today, OIs are less common in people with HIV because of effective treatment (CDC, 2021a).

HIV TRANSMISSION AND RISK FACTORS

An individual can only become infected with HIV through direct contact with certain body fluids from a person with HIV who has a detectable viral load. A detectable viral load is having more than 200 copies of HIV in a milliliter of blood.

Transmission Routes

Body fluids known to transmit HIV include:

- Blood

- Semen and preseminal fluids

- Rectal fluids

- Vaginal fluids

- Breast milk

In addition, any body fluid visibly contaminated with blood should be considered capable of transmitting HIV. These fluids may include:

- Cerebrospinal

- Amniotic

- Pleural

- Synovial

- Peritoneal

- Pericardial

For transmission to occur, the virus must enter the bloodstream of an HIV-negative person through a mucous membrane. These are located in the:

- Rectum

- Vagina

- Mouth

- Tip of the penis

The virus can also be transmitted through open cuts or sores or through direct injection (e.g., by a needle or syringe).

Unless blood is visibly present, HIV cannot be transmitted by:

- Saliva

- Sputum

- Sweat

- Tears

- Feces

- Nasal secretions

- Urine

- Vomitus

HIV also cannot be transmitted by:

- Air

- Water

- Donating blood

- Closed-mouth kissing

- Insects

- Pets

- Sharing food or drinks

- Sharing toilets

The main routes of HIV transmission are through:

- Unprotected sexual contact with an infected person

- Sharing needles and syringes with an infected person

- From an infected mother to child during pregnancy, during birth, or after birth while breastfeeding

Additional criteria for HIV transmission to occur include:

- HIV must be present in sufficient transmittable amounts.

- HIV must be able to enter the bloodstream of the next person.

HIV is a fragile entity and cannot survive for a substantial amount of time in the open air. The length of time HIV can survive outside the body is dependent on the amount of virus present in the body fluid and the conditions the fluid is subjected to. Studies have shown that when a high level of HIV that has been grown in a lab is placed on a surface, it loses most of its ability to infect (90%–99%) within several hours, indicating that contact with dried blood, semen, or other fluids poses little risk (HIV.gov, 2022a; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023).

SEXUAL CONTACT

HIV transmission rates vary by the type of sexual contact. The chances of contracting HIV after one exposure are highest among those who have receptive anal sex (about 1%). This means that someone can get the virus 1 out of every 100 times they have receptive anal sex without a condom. The reason for the higher risk of transmission by anal sex is due to the thin layer and easy penetrability of the cells in the anus compared to the vagina. HIV probability is lower for those having insertive anal sex, followed by receptive and insertive vaginal sex. With all three types of sex, the odds of contracting HIV after one exposure are well below 1% (Watson, 2022).

HIV acquisition rates among uncircumcised males are higher than for circumcised males. This may be related to a high density of HIV target cells in the male foreskin, including Langerhans cells and macrophages. Circumcision reduces the risk of female-to-male HIV transmission by 50%–60%; however, circumcision does not appear to decrease the risk of HIV transmission to the partner (Cohen, 2022).

INJECTION DRUG USE

Sharing injection needles, syringes, and other paraphernalia with an HIV-infected person can send HIV (as well as hepatitis B and C viruses and other bloodborne diseases) directly into the user’s bloodstream. About 1 in 10 new HIV diagnoses in the United States is attributed to injection drug use or the combination of male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use. The risk is high because needles, syringes, or other injection equipment may be contaminated with blood, which can survive in a used syringe for up to 42 days, depending on temperature and other factors. HIV-negative persons have a 1 in 160 chance of getting HIV every time they use a needle that has been used by someone else who has HIV. Sharing syringes is the second riskiest behavior following receptive anal sex (CDC, 2021b).

BLOOD TRANSFUSION

The chances that donated blood will contain HIV is less than 1 in nearly 2 million. While all blood donations are screened for HIV before they enter the blood pool, all laboratory tests have a “window period” in which very recent HIV infections cannot be detected, and in those most sensitive assays that are used by blood collection agencies, this window may be between 10–16 days. Because of this, a small number of infected samples still make it through testing (Tufts Medical Center, 2022).

TATTOOING, BODY PIERCING

There are no known cases in the United States of anyone becoming infected with HIV from professional tattooing or body piercing. There is, theoretically, a potential risk, especially during the time period when healing is taking place. It is also possible to become infected by HIV from a reused or not properly sterilized tattoo or piercing needle or other equipment, or from contaminated ink. The risk is very low but increases when the person doing the procedure is not properly trained and licensed (CDC, 2022b).

MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION

Before effective treatment was available, about 25% of pregnant mothers with HIV passed the virus to their babies. Today, if the mother is receiving HIV treatment and has a sustained undetectable viral load through pregnancy and postpartum, the risk of passing HIV to the baby is less than 1%. The risk of HIV transmission while breastfeeding is also less than 1% for women with HIV on antiretroviral therapy with sustained undetectable viral load through pregnancy and postpartum (USDHHS, 2021; NIH, 2023).

Other Factors Affecting Transmission Risk

Many other factors, alone or in combination, affect the risk of HIV transmission.

HIGH VIRAL LOAD

The higher someone’s HIV viral load, the more likely the person is to transmit HIV. Viral load is highest during the acute phase of HIV and without HIV treatment.

- A high HIV viral load is generally considered to be above 100,000 copies per milliliter of blood, but a person could have 1 million or more. At this point the virus is at work making copies of itself and the disease may progress quickly.

- A lower viral load is below 10,000 copies per milliliter of blood. At this point, the virus isn’t actively reproducing as fast and damage to the immune system may be slowed.

- An undetectable viral load is generally considered to be less than 20 copies per milliliter of blood. At this point the virus is suppressed. This does not mean, however, that there is no virus in the body; it just means there is not enough for the test to detect and count. People with HIV who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV sexually to their partners.

(IAPAC, 2021)

OTHER SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES/INFECTIONS (STDs/STIs)

People who have a sexually transmitted disease (also called sexually transmitted infection [STI]) may be at an increased risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. Some of the most common STDs include gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, trichomoniasis, human papillomavirus (HPV), genital herpes, and hepatitis.

One reason for this is that the behaviors that put people at risk for one infection often put them at risk for others. When a person with HIV acquires another STD such as gonorrhea or syphilis, it is likely they were having sex without using condoms. Also, STDs and HIV tend to be linked, and when someone gets an STD, it indicates they may have acquired it from someone who may be at risk for other STDs as well as HIV.

People with HIV are more likely to shed the virus when they have urethritis or a genital ulcer, and in a sexual partner, a sore or inflammation caused by an STD may allow infection that would have normally been stopped by intact skin. Even STDs that cause no breaks or open sores can increase the risk by causing inflammation that increases the number of cells that can serve as targets for HIV.

Both syphilis and HIV are highly concentrated among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). In 2021, MSM only and men who have sex with both men and women accounted for 63% of all primary and secondary syphilis cases in which the sex of the partner was known. HIV is more closely linked to gonorrhea than chlamydia (common among young women), and herpes simplex (HSV-2) is commonly associated with HIV. Studies have shown that persons infected with herpes are at three-times higher risk for acquiring HIV infection (CDC, 2023c).

HIV TESTING AND COUNSELING

An estimated 1.2 million people in the United States are infected with HIV, including about 158,500 people who are unaware of their status. Nearly 40% of new HIV infections are transmitted by people who do not know they have the virus.

HIV testing is the first step in preventing transmission of the virus to others. HIV tests are quite accurate, but no test can detect the virus immediately after infection (CDC, 2022e).

Types of HIV Tests

There are three types of HIV tests: antibody tests, antigen/antibody tests, and nucleic acid tests (NAT).

ANTIBODY TESTS

Antibody tests detect antibodies to HIV in the person’s blood or oral fluid. Antibody tests have a window of 23–90 days before HIV can be detected after an exposure. Antibody tests that use blood from a vein can detect HIV sooner after infection than tests performed with blood from a finger stick or with oral fluid.

Most rapid tests and HIV self-tests are antibody tests. Examples of antibody tests include:

- OraQuick In-Home HIV Test (self-test)

- OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 (rapid test)

- SURE CHECK HIV 1/2 Assay (rapid test)

(CDC, 2022e)

ANTIGEN/ANTIBODY TESTS

Antigen/antibody tests look for both HIV antibodies and antigens. Antibodies are produced by a person’s immune system following an exposure to a virus such as HIV. Antigens are foreign substances that cause a person’s immune system to activate. If a person becomes infected with HIV, the antigen p24 is produced before antibodies develop.

An antigen/antibody test performed by a lab on blood from a vein can usually detect HIV 18–45 days after exposure. There is also a rapid antigen/antibody test available that is performed with a finger stick. Antigen/antibody tests with blood from a finger stick can take from 18–90 days after exposure to detect HIV. Examples of antigen/antibody tests include:

- ADVIA Centaur HIV Ag/Ab

- Alere Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combi (rapid test)

(CDC, 2022e)

NUCLEIC ACID TESTS (NATs)

An NAT directly tests for HIV in the blood. This test is recommended for those who have had a recent exposure or a possible exposure with early symptoms of HIV and have tested negative with an antibody or antigen/antibody test. The window period before detection can occur for a NAT is 10–33 days following exposure. Examples of NATs include:

- Cobas HIV-1/HIV-2 Qualitative

- Aptima HIV-1 Quantitative DX Assay

- Alinity m HIV-1

(CDC, 2022e)

Testing Recommendations

The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 be tested for HIV at least once as part of routine healthcare.

Recommendations call for people with higher risk factors to be tested at least annually. These individuals include:

- Sexually active gay or bisexual men (some of whom may benefit from even more frequent testing, such as every 3–6 months)

- People who have had sex with an HIV-positive partner

- People who have had more than one partner since their last HIV test

- Those who have shared needles (“works”) to inject drugs

- People who have exchanged sex for drugs or money

- People who have another sexually transmitted disease, hepatitis, or tuberculosis

Additionally, HIV testing is recommended for:

- All pregnant women

- Any newborn whose mother’s HIV status is unknown

- Anyone who has been sexually assaulted (If the assault is considered a high risk for HIV exposure, the person’s baseline HIV status should be established within 72 hours after the assault and the person then tested periodically as directed by healthcare personnel.)

The CDC recommends that all HIV screening be voluntary. Separate written consent for an HIV test is not recommended. A general informed consent for medical care that notifies the patient that an HIV test will be performed is recommended, and the person can voluntarily accept the test (opt-in) or decline it (opt-out).

HIV testing is mandatory in the United States for:

- Blood and organ donors

- Military applicants and active-duty personnel

- Federal and state prison inmates

- Newborns in some states

Testing Sites

HIV tests are generally available in many places, including:

- Healthcare providers’ offices

- Health clinics or community health centers

- STD/STI or sexual health clinics

- Local health departments

- Family planning clinics

- VA medical centers

- Substance abuse prevention or treatment programs

- Many pharmacies

- Mobile testing vans and community events

- Home testing kits available in pharmacies or online

(HIV.gov, 2022b)

These sites can connect people to HIV care and treatment if they test positive or can discuss the best HIV prevention options if they test negative.

HIV Test Results

When testing is performed in a healthcare provider’s office, a clinic, or a community setting, results will be explained and the patient given instructions about the next steps. If a rapid HIV self-test is done at home, the package material will provide the explanation of the results and instructions for the next steps, along with a contact phone number.

A negative HIV test result does not necessarily mean that the person is not infected with HIV. This is due to the window period after exposure, which varies from person to person and depends on the type of test taken. A window period refers to the time between HIV exposure and when a specific type of test can detect HIV in the body. Therefore, when a person tests negative, it does not necessarily mean the person does not have HIV. If the person is tested again after the window period, has had no possible HIV exposure during that time, and the result is negative again, the person does not have HIV.

For a positive antibody test, a follow-up test is required to confirm the results. If a rapid screening test was performed in a healthcare setting, a follow-up test should be arranged to make certain the initial result was correct. For a positive self-test, the person should visit a healthcare provider for follow-up testing. If the blood test was performed in a healthcare setting or a lab, the lab will conduct a follow-up test on the same sample as the first test (HIV.gov, 2022c).

An HIV test can also return an indeterminate, equivocal, or invalid result. This means the test result is unclear and that another test is necessary. Indeterminate results can occur in people following recent HIV infection, due to antibody cross-reaction, or because of another technical error. If an indeterminant result is not reproduced in repeat testing, it is almost certainly a false-positive reaction (Pebody, 2021).

At times, an HIV test will return a false-positive result. This is why it is essential that all patients with a positive or indeterminant screening result undergo confirmatory testing. The main cause of false-positive results is that the test has detected antibodies to a substance or infection other than HIV. HIV tests are not meant to react to other types of antibodies, but sometimes they do (Tsoi et al., 2022; Pebody, 2021).

HIV Pre- and Post-Test Counseling

HIV counseling is intended to allow people to make informed decisions based on knowledge of their HIV status and the implications of their decisions. Counseling is a gateway to prevention care, treatment, and support. Although not required, HIV counseling is often provided both pre-test and post-test, and can be done by nonmedical personnel.

Pre-test counseling can be provided in person, by prerecorded video, or by pamphlet. Pre-test counseling enables the patient to become aware of the risks and adequacy of the timing of taking the test (to avoid testing in the window period), informs the person of the benefits of having the test done, and discusses the implications of both positive and negative results. Persons are assured to have the right to refuse to take an HIV test. This information is vital for obtaining informed consent. Also, during pre-test counseling the person is encouraged to anticipate the possibility of disclosure of HIV status, for example, to a sexual partner or family, and is provided with preventive information and material.

Post-test counseling informs HIV-positive persons of their options. They are advised and referred for further care, treatment, and support services as needed. Additionally, disclosure of positive status to relevant others is discussed and encouraged, along with the provision of prevention information and material (WHO, 2023; CDC, 2021e).

CLINICAL STAGES AND MANIFESTATIONS OF HIV AND AIDS

Following transmission of the virus, the individual will typically progress through three stages of illness.

- Stage 1: Acute infection is the earliest stage, when seroconversion takes place and the person is very contagious.

- Stage 2: Clinical latency or chronic HIV. During this stage, the virus is still active and continues to reproduce. This stage can last for 10–15 years, and immunosuppression gradually develops. The person may be asymptomatic and can transmit the virus to others. People who receive HIV treatment as prescribed may never move into the next stage (AIDS).

- Stage 3: Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is the final, severe stage of HIV infection, at which point the immune system is severely damaged and opportunistic infections or cancers begin to appear. The person with AIDS can have a high viral load and may easily transmit HIV to others.

(CDC, 2022b)

Acute Infection

About 10%–60% of people with early HIV infection will not experience any symptoms. In those that do, the usual time from HIV exposure to development of symptoms is 2–4 weeks. This incubation period, however, has been known to last as long as 10 months. Clinical manifestations can include:

- Fever, fatigue, myalgia

- Adenopathy

- Sore throat

- Mucocutaneous ulcerations

- Rash

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Neurological symptoms

- Respiratory symptoms

- Opportunistic infections

- Oral and esophageal candidiasis

- Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia

- Prolonged severe cryptosporidiosis

Clinical Latency or Chronic HIV

Following acute infection when the body loses the battle with HIV, the symptoms disappear and the person moves into the second stage, referred to as the chronic infection or clinical latency phase. During this period, the virus continues to multiply at very low levels, there is a steady decline in the CD4 cell count, and immunosuppression gradually develops.

People in this stage may not feel sick or have any symptoms. Without antiretroviral therapy, people can remain in this stage for 10–15 years, but some will move through it more quickly. Most people have few to no symptoms prior to the development of severe immunosuppression. During this stage, however, the person can still transmit the virus to others (HIV.gov, 2023b).

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

Without HIV treatment and when the CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells per milliliter, the person will then progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). This is the last stage of the illness, at which point the immune system is severely damaged and opportunistic infections or cancers begin to appear. The person can have a high viral load and may easily transmit HIV to others. Without HIV medications, people with AIDS typically survive for about three years. Once someone has a dangerous opportunistic infection, life expectancy without treatment falls to about one year.

OPPORTUNISTIC INFECTIONS (OIs)

Many of the severe symptoms of HIV disease at this stage result from common opportunistic infections and include:

- Candidiasis affecting the skin, nails, and mucous membranes, especially in the mouth, vagina, and esophagus.

- Invasive cervical cancer.

- Coccidiomycosis, also known as valley fever, desert fever, or San Joaquin Valley fever, is caused by breathing in fungal spores. It is common in hot, dry regions of the southwestern United States, Central America, and South America.

- Cryptococcosis, a fungal infection that affects the lungs or central nervous system as well as other parts of the body.

- Cryptosporidiosis, which is caused by a parasite that enters through contaminated food or water. Symptoms include abdominal cramps and severe, chronic watery diarrhea.

- Cystoisosporiasis from a parasite in contaminated food or water, which causes diarrhea, fever, headache, abdominal pain, vomiting, and weight loss.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) affecting multiple parts of the body, causing pneumonia, gastroenteritis, encephalitis, and retinitis that can lead to blindness.

- HIV encephalopathy, whose exact cause is unknown but thought to be related to infection of the brain and resulting inflammation.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV), which is usually acquired sexually or passed from mother to child during birth. HSV normally is latent in those with healthy immune systems, but HIV can reactivate the latent virus, and symptoms can return. HSV causes painful cold sores in or around the mouth or painful ulcers on or around the genitals or anus. It can also cause infection of the bronchus, pneumonia, and esophagitis.

- Histoplasmosis, a fungal infection that develops mostly in the lungs and causes symptoms similar to flu or pneumonia. Those with severely damaged immune systems can develop progressive disseminated histoplasmosis that can spread to other parts of the body.

- Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a viral illness that causes small blood vessels to grow abnormally anywhere in the body. It appears as firm pink or purple raised or flat spots on the skin. It can be life-threatening when it affects organs such as the lungs, lymph nodes, or intestines.

- Lymphoma refers to cancer of the lymph nodes and other lymphoid tissues. Some types of lymphomas associated with HIV are non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Generalized lymphadenopathy is found on physical exam. The nodes are mostly symmetrical, moderately enlarged, mobile, painless, rubbery, and located in the cervical, submandibular, occipital, and axillary chains.

- Tuberculosis is caused by breathing in a bacterium that usually attacks the lungs, but it can affect any part of the body, such as the kidneys, spine, and brain. Symptoms include cough, tiredness, weight loss, fever, and night sweats.

- Mycobacterial avium complex (MAC) are bacteria that live in the environment, including in soil and dust particles, and which cause lung disease that can be life threatening.

- Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is a fungal lung disease that causes difficulty breathing, high fever, and dry cough.

- Pneumonia can be caused by many agents, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. The most common and life-threatening cause in those with HIV is Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy is a rare viral brain and spinal cord disease causing loss of muscle control, paralysis, blindness, speech problems, and altered mental state; it can progress rapidly and may be fatal.

- Salmonella septicemia is a severe form of infection that exceeds the immune system’s ability to control it.

- Toxoplasmosis is caused by a parasite carried by warm-blooded animals and released in their feces. Infection can occur in the lungs, retina of the eye, heart, pancreas, liver, colon, testes, and brain.

- Wasting syndrome is the involuntary loss of more than 10% of body-weight due to HIV-related diarrhea or weakness and fever for more than 30 days.

(CDC, 2021a; HIV.gov, 2023b)

OTHER COMPLICATIONS

Other complications resulting from HIV infection can include:

- AIDS dementia complex (ADC), also known as HIV encephalopathy or HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), can range from mild symptoms of behavioral changes and reduced mental functioning to severe dementia causing weakness and inability to function. Not all patients with HAND progress to HIV-associated dementia.

- HIV-associated dementia (HAD) patients demonstrate deficits in memory, abstraction, verbal ability, decision-making, and attention. Rare features include sleep disturbances, psychosis (with mania), and seizures. Motor problems include imbalance, clumsiness, and weakness. In some extreme cases, vegetative state and mutism are also seen.

- HIV-associated progressive encephalopathy (HPE) can occur in infants with HIV. Features may include decline in intellectual and motor milestones. In young children, the rate of acquiring new skills decreases, and fine motor ability and dexterity may become impaired. In older children and adolescents, the presentation is like that of AIDS dementia complex (ADC).

- HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) causes progressive acute renal failure due to direct HIV infection of renal epithelial cells and is closely associated with individuals of African descent (96%–100%).

- Liver diseases are also a major complication, especially in those who also have hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection.

(Reilly, 2022; Mayo Clinic, 2022; Wyatt & Fisher, 2023)

Less commonly, people with HIV/AIDS may develop the following cancers:

- Angiosarcoma, which begins in the lining of the blood vessels

- Anal cancer

- Liver cancer

- Mouth and throat cancers

- Lung cancer

- Testicular cancer

- Penile cancer

- Colorectal cancer

- Skin cancers, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma

(ASCO, 2021)

HIV/AIDS INFECTION AMONG CHILDREN

Signs and symptoms of HIV/AIDS among the pediatric population include:

- Unusually frequent occurrences of common childhood bacterial infections, such as otitis media, sinusitis, and pneumonia, which can be more severe than they are in immunologically healthy children

- Recurrent fungal infections, such as candidiasis, that do not respond to standard antifungal agents, suggesting lymphocytic dysfunction

- Recurrent or unusually severe viral infections, such as disseminated herpes simplex, zoster infection, or cytomegalovirus retinitis, seen with moderate-to-severe cellular immune deficiency

- Growth failure, failure to thrive, or wasting, which may indicate HIV infection when other common metabolic and endocrine disorders do not appear to be the etiologies and may signify disease progression or underlying malnutrition

- Failure to attain typical milestones, suggesting developmental delay, particularly impairment in the development of expressive language, which may indicate HIV encephalopathy

- Loss of previously attained milestones, which may signify a CNS insult due to progressive HIV encephalopathy or opportunistic infection

- In older children, behavioral abnormalities (e.g., loss of concentration and memory), which may indicate HIV encephalopathy

- Recurrent bacterial infections (especially invasive infections), such as bacteremia, meningitis, and pneumonia, or unusual infections such as those caused by the Mycobacterium avium–intracellulare complex

Older children and young teenagers can have HIV infection or AIDS without a history of immunodeficiency or severe illness. Fever of unknown origin, recurrent infection, growth failure, or developmental regression without obvious etiology should raise suspicion of HIV infection (Rivera, 2020).

ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY (ART)

Antiretroviral therapy involves taking a combination of HIV medicines every day. ART is recommended for everyone who has HIV and should be started as soon as possible. People on ART take a combination of HIV medicines every day, and initially the regimen generally includes three HIV medicines from at least two different HIV drug classes. ART cannot cure HIV, but HIV medicines help people with HIV live longer, healthier lives. ART also reduces the risk of HIV transmission.

Goals of HIV treatment are to:

- Reduce the viral load in the body to an undetectable level

- Reduce the risk of HIV transmission

- Prevent HIV from advancing to AIDS

- Protect the immune system

ART is recommended to be offered to all HIV-infected patients, including infants and children, even when they are asymptomatic, regardless of their immune status. For most patients, ART should be initiated soon after an initial diagnosis is made. Initiating ART at the first visit improves outcomes and adherence to care (HIV.gov, 2023c).

Types of Antiretroviral Medications

For most people, an ART regimen consists of a combination of these various classes of medications.

| Drug Class | Generic (Brand) Name |

|---|---|

| (HIV.gov, 2023c) | |

| Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs): inhibit transcription of viral RNA into DNA |

|

| Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs): inhibit transcription of viral RNA into DNA |

|

| Protease inhibitors (PIs): block an enzyme needed to make copies of the virus |

|

| Fusion inhibitors (FIs): inhibit the binding and fusion with a CD4 cell |

|

| Integrase inhibitors (INSTIs): inhibit an enzyme needed to make copies |

|

| Chemokine receptor antagonists (CCR5 antagonists): inhibit entry into the cell |

|

| Attachment inhibitors: inhibit entry into the cell |

|

| Post-attachment inhibitors: block CD4 receptors on the surface of certain immune cells that HIV needs to enter the cells |

|

| Capsid inhibitors: interfere with replication |

|

| Pharmacokinetic enhancers: increase effectiveness of an HIV medicine |

|

Initiating ART

ART is recommended for all persons with HIV beginning as soon as possible following diagnosis to prevent complications of HIV, to reduce morbidity and mortality, and to prevent transmission of HIV to others.

Prior to initiation of ART, laboratory testing for drug resistance should be obtained. ART can be started, however, before test results are available.

Antiretroviral therapy is individualized and based on factors such as:

- Comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular disease, chemical dependency, liver disease, psychiatric disease, renal diseases, osteoporosis, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis

- Potential adverse drug effects

- Potential drug interactions with other medications

- Pregnancy or pregnancy potential

- Results of genotypic drug-resistance testing

- Specific tests regarding the medication to be considered

- Patient adherence potential

- Convenience (pill burden, dosing frequently, food and fluid considerations)

- Drug availability and cost

Initiation of therapy may be delayed due to certain opportunistic infections that may worsen clinically with commencement of ART, a condition known as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) (Bokhari, 2022).

ART Monitoring

Patients follow-up takes place within four weeks of starting treatment. At that time, laboratory testing is done to monitor the virologic and immunologic response.

After the initial visit, patients are typically seen every three to six months to assess for adherence and therapeutic response and to identify adverse events related to the chronic administration of these medications. Once the patient is clinically stable on their regimen with viral suppression, visit frequency and laboratory testing is typically done every six months.

Adherence Issues

Adherence to ART is a principal determinant of virologic suppression. Suboptimal adherence may include missed or late doses, treatment interruptions or discontinuations, and subtherapeutic or partial dosing. Poor adherence can result in a subtherapeutic plasma drug concentration, which may subsequently result in resistance to one or more drugs and cross-resistance to other drugs in the same class.

For each clinic visit, a routine adherence assessment is conducted. Viral loading is the most useful indicator of adherence and a routine component of monitoring individuals who are on ART. This evaluation assesses psychosocial and behavioral factors that may influence adherence, and interventions to help decrease such barriers should be supported.

Approaches to improve adherence address each person’s needs and barriers and might include:

- Discussing medication schedules to assist in pill-taking behaviors to link them to other daily activities (e.g., brushing teeth)

- Changing ART to simplify dosing or to reduce side effects

- Allowing flexible appointment scheduling

- Finding resources to assist with treatment cost to maintain uninterrupted access to both ART and appointments

- Linking patients to resources to assist with unmet social and economic needs, such as transportation, food, housing, and support services

- Linking patients to counseling to deal with stigma, substance use, or depression

Patients are advised to notify the provider if there is an anticipated issue with adherence, such as elective surgery or a prolonged illness (HIV.gov, 2023e; Gardland, 2023).

Antiretroviral Therapy Side Effects and Complications

Today’s HIV medications have fewer side effects, fewer people experience them, and they are less severe than in the past. Side effects can differ from person to person and depend on the type of medication. Some side effects occur at the start of taking a medication and may last only a few days or weeks, while other side effects begin later and last longer (HIV.gov, 2023e).

The focus of patient management is on individualized therapy to avoid long-term adverse effects. There are several factors that predispose patients to adverse effects, including:

- Concomitant use of medications with overlapping and additive toxicities

- Comorbid conditions that increase the risk of or exacerbate adverse effects, such as alcoholism or viral hepatitis

- Borderline or mild renal dysfunction, which increases risk of nephrotoxicity

- Drug-drug interactions

- Certain medications may exacerbate pre-existing psychiatric disorders

- Genetic factors that predispose patients to hypersensitivity reaction, neuropsychiatric toxicity QT interval prolongation, or hyperbilirubinemia

(HIV.gov, 2023e)

Indications for Changing ART Medication

On occasion, assessments find that the current regimen requires changing. Common reasons for changing the regimen include:

- Failure of the medication(s) to suppress viral load

- Adverse effects related to toxicity

- Intolerance to the medications

- Inconvenience or preference, such as frequency of dosing, pill burden, or requirements for co-administration with food

(Gardland, 2023)

DRUG RESISTANCE

HIV drug resistance is caused by mutations to the virus’s genetic structure that are slightly different from the original virus. As the virus multiplies in the body, it sometimes mutates. This can occur while a patient is taking HIV medications, leading to the development of drug-resistant HIV. Once drug resistance develops, the medications that controlled a patient’s HIV are no longer effective. HIV treatment failure results, and the person can transmit the virus to another individual, who will than have reduced treatments available.

Drug-resistance testing is done after HIV is diagnosed but before the person starts taking HIV medications in order to help determine which HIV medications are or are not to be included in the patient’s first HIV regimen. Once HIV treatment is started, a viral load test is used to monitor whether the medications are controlling the patient’s HIV. If testing indicates that the person’s HIV regimen is not effective, drug-resistance testing is repeated. These test results can identify whether drug resistance is the problem, and if so, they can be used to select a new regimen (HIV.gov., 2023e).

PATIENT CARE MANAGEMENT

It is the role of primary healthcare providers to oversee and coordinate the multidisciplinary services necessary for the best health outcomes for HIV-infected patients. Following initial evaluation, follow-up visits depend on the patient’s stage of HIV infection, the type of antiretroviral therapy the patient is taking, other comorbidities, and complications.

Once started on ART, the patient makes frequent healthcare visits to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of the selected regimen. Once the viral load has been suppressed, however, less frequent monitoring is appropriate. Most patients with HIV who are on an effective ART regimen die from conditions other than AIDS, and they have a higher risk of certain medical conditions that might be associated with HIV infection itself, risk factors prevalent in those with HIV, or the use of ART. Appropriate management requires an awareness about and evaluation of these possible complications

Case Management

There are many people with HIV who do not start or stay in care to control their HIV. A recent estimate found that only 66% of those diagnosed with HIV connected with a doctor for care and only 50% stayed in care.

Case managers are professionals who connect patients with a range of social services and assist with any challenges the person may have that keeps them from getting into and remaining in care. A case manager assesses what specific services are required and then assists the person in accessing them. An HIV case manager may assist with:

- Setting up medical and dental appointments

- Finding affordable health insurance or government insurance

- Applying for financial aid to help cover living expenses, such as Social Security or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF)

- Applying for housing, finding an apartment, and paying for the first months’ rent

- Obtaining short-term help to pay for utilities or cell phone services

- Finding free transportation to clinic appointments or free bus/transit passes

- Obtaining free groceries at a local food bank

- Obtaining counseling for mental health conditions or treatment for substance abuse

- Applying for free HIV medications through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP)

- Managing pregnancy, prenatal care, delivery, and infant care

- Finding HIV support groups

- Obtaining a referral to a lawyer for legal assistance

(Felson, 2022)

Managing Coexisting Infections

Patients should be regularly screened for infections, including:

- Tuberculosis testing (TST or IGRA) at baseline and annually for those at risk unless there is a history of a prior positive test, with a chest X-ray to rule out active TB in patients with a positive screening test

- Syphilis serology at baseline and annually for sexually active persons

- Chlamydia and gonorrhea screening at baseline and annually for sexually active persons

- Trichomonas baseline for all women and annually for sexually active women

- Hepatitis A and hepatitis B virus serologies at baseline, along with vaccinations in persons not immune

- Hepatitis C virus serology, with reflex viral level, for positive result at baseline and annually in those at risk (e.g., persons who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, transgender women)

- Dilated fundoscopic exam annually in patients with CD4 cell count less than 50/microL, as HIV-1 infected patients are prone to develop ocular opportunistic infections, including:

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis

- Cryptococcosis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Tuberculosis

Taking HIV medicine is the best way to prevent getting infections, and patients should be counseled in strategies to prevent them, including immunization. There are many medications to treat HIV-related infections, including antivirals, antibiotics, and antifungal drugs. Once an infection is successfully treated, a person may continue to use the same medication or an additional medication to prevent the opportunistic infection from returning (Pollack & Libman, 2023; HIV.gov, 2023f).

Ongoing Management of HIV Symptoms

Common symptoms among people living with HIV can include acute and/or chronic pain, as well as fatigue.

ACUTE/CHRONIC PAIN

Chronic pain affects 25%–85% of individuals with HIV infections. There is also much evidence that chronic pain is often underdiagnosed and undertreated among this population.

People with HIV can experience a variety of types of pain from a variety of causes. The virus itself and the immune response to it can lead to inflammatory responses causing pain. Secondary complications of poorly managed HIV, such as cancers and opportunistic infections, are also associated with pain. Older HIV medications themselves tend to be neurotoxic and associated with nerve damage that can lead to chronic pain. Even those patients who are managing their infection with ART and have higher CD4 counts can experience pain.

The most commonly reported pain syndromes include painful sensory peripheral neuropathy, headache, oral and pharyngeal pain, abdominal pain, chest pain, anorectal pain, joint and muscle pain, as well as painful dermatologic conditions and pain due to extensive Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Women with HIV appear to experience pain more frequently than men and report somewhat higher levels of pain intensity. This may partly be due to the fact that HIV-positive women are twice as likely as men to be undertreated for their pain (Pahuja et al., 2023).

Research also suggests women are more sensitive to pain than men and are more likely to express it, so their pain is often seen as an overreaction rather than a reality. Research also shows that due to provider and societal bias, men in chronic pain tend to be regarded as “stoic” while women are more likely to be considered “emotional” and “hysterical” (Latifi, 2021).

Children with HIV can also experience pain due to conditions such as meningitis and sinusitis, otitis media, cellulitis and abscesses, severe candida dermatitis, dental caries, intestinal infections, hepatosplenomegaly, oral and esophageal candidiasis, and spasticity associated with encephalopathy causing painful muscle spasms.

Because of the high prevalence of chronic pain and the evidence that links chronic pain with outcomes, individuals with HIV infection are routinely and frequently asked about pain. As with other patients with chronic pain, an evidence-based diagnostic evaluation is performed.

Opioids are not used as first-line treatment options for chronic pain. Generally, the approach to chronic pain management includes initial psychoeducation about the nature of pain as a chronic condition and the significance of multimodal therapies, such as physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, or supportive psychotherapy, and setting expectations that the timeline for improvement is not days or weeks but instead months or years (Pahuja et al., 2023).

FATIGUE

Fatigue is a common, often persistent symptom among individuals with HIV infection. Fatigue interferes with physical, social, and mental functioning, and may also interfere with adherence to ART.

Physiologic factors associated with fatigue or the severity of fatigue include liver disease, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, anemia, and duration of HIV infection. Fatigue can also be caused by the HIV itself, and it is known that the body mounts a strong immune response against the virus, which can use up a lot of energy.

Psychological and social factors associated with fatigue include stressful life events, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder.

For individuals with HIV, the approach to fatigue is the same as in the general population. This includes a search for medical or psychiatric causes (especially hypogonadism), medication review, inquiry regarding the patient’s sleep patterns, and treatment of the underlying cause when present. Testosterone may help hypogonadal men with fatigue. Moderate exercise is a reasonable recommendation also if patients are able to tolerate it (Pahuja et al., 2023).

NUTRITION AND WEIGHT LOSS

Weight loss of more than 5% in persons with HIV infection is associated with faster disease progression, impaired functional status, and increased mortality. It is affected by factors including the HIV disease stage, nutritional status, and micronutrient deficiencies.

Starting nutritional counseling and education shortly after HIV diagnosis is important, since good nutrition has been shown to increase resistance to infection and disease and improve energy. Severe malnutrition in HIV-infected patients is recognized as “wasting syndrome,” defined by the CDC as a body-weight loss equal to or greater than 10%, with associated fatigue, fever, and diarrhea unexplained by another other cause.

Nutritional assessment includes:

- Measurement of weight, noting weight change, height, body mass index (BMI), and mid-upper-arm circumference

- Appetite, difficulty swallowing, nausea, diarrhea, and effects of drug-food interaction

- Household food security

Management includes:

- Supplementary feeding in those who are mild to moderately malnourished, regardless of HIV status

- Therapeutic food for severely malnourished adults

- Increased energy intake by 10% in patients with asymptomatic HIV infection

- Multivitamin supplements

In those who are in the early stages of AIDS, weight gain and/or maintenance has been shown to be possible with a high-energy, high-protein diet, including at least one oral liquid nutrition supplement in conjunction with nutrition counseling.

Pharmacologic therapy can include the anabolic replacement with synthetic testosterone, which has been shown to increase lean body mass and improve quality of life among androgen-deficit men. Megestrol, a synthetic oral progestin approved by the FDA for treatment of anorexia, cachexia, or unexplained weight loss, has been shown to stimulate appetite and nonfluid weight gain in patients with HIV/AIDS (Qureshi, 2021).

NEUROPSYCHIATRIC EFFECTS OF HIV/AIDS

HIV itself increases the risk of neuropsychiatric conditions because it causes major inflammation within the body. The entire brain, including the lining, becomes inflamed as a result of the body’s immune response, causing irritation and swelling of brain tissue and/or blood vessels, resulting in nontraumatic brain damage over the long term. Having brain damage such as this is a known risk factor for the development of a neuropsychiatric condition.

Because HIV affects the immune system, the person also has an increased risk for other infections that can affect the brain and nervous system and lead to changes in behavior and functioning.

Starting antiretroviral therapy can also affect a person’s mental health in different ways. Some antiretroviral medications have been known to cause symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance and may make some mental health conditions worse (MHA, 2023; Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

HIV-ASSOCIATED NEUROCOGNITIVE DISORDERS (HAND)

Changes in attention, memory, concentration, and motor skills are common among HIV-infected individuals. When such changes are clearly attributable to HIV infection, they are classified as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Depending on the severity and impact on daily functioning, cognitive deficits can be further classified into three conditions:

- Asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI)

- HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder (MND)

- HIV-associated dementia (HAD)

The widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy has been associated with a decrease in the prevalence of more severe neurocognitive deficit, such as HAD, but milder cognitive deficits without alternative explanation remain common, even among patients with viral suppression.

HAND is characterized by the subacute onset of cognitive deficits, central motor abnormalities, and behavioral changes. Risk factors for HAND include a low nadir CD4 cell count, age, and other comorbidities, such as cardiovascular and metabolic disease.

The main cognitive deficits that have been reported in milder presentations of HAND include problems with attention and working memory, executive functioning, and speed of informational processing. The onset and course are generally more slow-moving, and deficits may remain stable or apparently unchanged for years.

HAD is related to the effect of HIV on subcortical and deep grey matter structures and occurs mainly in patients who are untreated with advanced HIV infection. Unlike other neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease), deficits occurring in HAD may come and go over time. Onset of impairment is most often subacute, and cerebral atrophy is often evidenced on brain imaging.

Risk factors for HAD include high serum or cerebrospinal fluid HIV viral load, low education level, advanced age, anemia, illicit drug use, and female gender. The dementia is characterized by subcortical dysfunction with:

- Attention-concentration impairment

- Depressive symptoms

- Impaired psychomotor speed and precision

Patients with HAD may also have changes in mood that can progress to psychosis with paranoid ideation and hallucinations, and some may develop mania (Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

Issues Affecting Special Populations

HIV/AIDS takes a heavy toll on people of all ethnicities, genders, ages, and income levels. However, some populations have been uniquely affected by the epidemic.

SEXUAL MINORITIES

The high prevalence of mental health problems among sexual minorities has been attributed to sexual minority stress. Minority stress may contribute to identity conflict and increase condomless anal sex by isolating men who have sex with men, transgender women, and gender nonbinary people of color (Sarno et al., 2022).

PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS

People with HIV who use injection drugs are a population with extensive psychiatric, psychological, and medical comorbidities, the most significant being major depression. Depression is associated with worsening of addictions and resistance to treatment. Patients who are depressed patients often find it difficult to engage in, invest in, and sustain treatment.

Because drug use is criminalized, people who use drugs often live or take drugs in underground, hidden places, making it harder for services to reach them. Healthcare workers, police, and other law enforcement agents are often discriminatory toward people who use drugs, which prevents them from wanting to access HIV services (Be in the KNOW, 2023b).

ADOLESCENTS WITH PERINATAL HIV INFECTION

The prevalence of mental health disorders in youth with perinatally acquired HIV is high, with nearly 70% meeting the criteria for a psychiatric disorder at some point in their lives. The most common conditions include anxiety and behavioral disorders, mood disorders (including depression), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, all of which complicate adherence to treatment and retention in care. The prevalence of attempted suicide is also notably higher in adolescents with HIV compared to others.

Adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV are also at risk for neurocognitive impairment and substance use disorders, which also can interfere with medication adherence.

Challenges that affect the treatment of adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV include extensive drug resistance, complex regimens, the long-term consequences of HIV and antiretroviral exposure, the developmental transition to adulthood, and psychosocial factors.

Assessment of antiretroviral adherence in adolescents with HIV can be challenging, with discordance between self-report and other adherence measures, such as viral load and therapeutic or cumulative drug levels. This should involve immediate and open discussions with the adolescent and their caregiver(s) (HIV.gov, 2023e).

End-of-Life Issues

Because of the advancement of effective antiretroviral therapy, the increased life expectancy for persons diagnosed with HIV is contributing to a rapidly aging HIV-infected population with a high prevalence of comorbidities. These comorbidities, and not HIV, are most often the cause of death for people in this population.

For patients with HIV/AIDS who are approaching the end of life, creating advance directives that outline their choices and preferences for care can be difficult. One of the most important decisions is whether and when to discontinue ART. This is particularly stressful for both the patient and family because it may be seen as “giving up.”

Individuals who are dying from a condition besides AIDS must consider whether or not to continue to receive antiretroviral treatment. Reasons for continuing ART may include:

- Discontinuance will lead to uncontrolled viremia, which could contribute to symptom burden.

- ART may help sustain cognitive functioning, as system viral load does not always correlate with central nervous system viral load.

Reasons for considering discontinuation of ART may include:

- Continuing medications might contribute to anxiety for patients who have trouble taking medication, cause confusion about goals, and distract from advanced care planning.

- Patients may experience “pill burden” and potential drug-drug interactions with common palliative care medication. For example, some ART medications increase levels of some opioids (e.g., oxycodone) while decreasing the levels of other opioids (e.g., methadone).

With continued treatment, the patient may choose palliative care. If treatment for HIV is to be discontinued, the choice for hospice care during the last six months of life recognizes that treatment is no longer of benefit and the disease will run its course (Pahuja et al., 2023).

HIV PREVENTION AND RISK REDUCTION STRATEGIES

HIV is preventable. Nevertheless, new infections continue to occur despite the knowledge available about how the virus is transmitted and the means to prevent its transmission or acquisition.

Individual Risk Reduction

A patient’s individual HIV risk can be determined through risk screening based on self-reported behavioral risk and clinical signs or symptoms. In addition to an assessment of behavioral risk, a comprehensive STI and HIV risk assessment includes screening for HIV and STIs. After a sexual history has been obtained, all providers can encourage risk reduction by offering prevention counseling to all sexually active adolescents and to all adults who have received an STD diagnosis, have had an STD during the prior year, or who have had multiple sex partners. Such counseling can reduce behaviors that result in higher risk of HIV infection.

ASSESSING BEHAVIORAL RISKS

Behavioral risks can be identified either through open-ended questions by the provider or through screening questions (e.g., a self-administered questionnaire). An example of an open-ended question is: “What are you doing now or what have you done in the past that you think may put you at risk of HIV infection?”

Common risk assessment questions can include:

- Have you or your sexual partner(s) had other sexual partners in the past year?

- Have you ever had a sexually transmitted infection?

- Are you pregnant or considering becoming pregnant?

- Have you or your sexual partner(s) injected drugs or other substances and/or shared needles or syringes with another person?

- Have you ever had sex with a male partner who has had sex with another male?

- Have you ever had sex with a person who is HIV infected?

- Have you ever been paid for sex (e.g., money, drugs) and/or had sex with a prostitute/sex worker?

- Have you engaged in behavior resulting in blood-to-blood contact (e.g., S&M, tattooing, piercing)?

- Have you been the victim of rape, date rape, or sexual abuse?

- Have you had unprotected anal or vaginal sex?

- How do you identify your gender (male, female, trans, other)?

(Skidmore College, 2023)

PREVENTION COUNSELING AND BEHAVIORAL STRATEGIES

Studies have shown that risk reduction and prevention counseling decreases the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. Counseling can range from brief messages, to group-based strategies, to high-intensity behavioral discussions tailored to the person’s risk. It is most effective if provided in a manner appropriate to the patient’s culture, language, sex and gender identity, sexual orientation, age, and developmental level. Client-centered counseling and motivational interviewing can also be effective. Training in these methods is available through the National Network of STD Prevention Centers (see also “Resources” at the end of this course) (CDC, 2021f).

Healthcare providers can counsel patients in behavioral strategies to prevent the spread of HIV infection, including:

- Sexual abstinence, since not having oral, vaginal, or anal sex is the only 100% effective option to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV

- Limiting the number of sex partners, since the more sex partners one has, the more likely one of them has poorly controlled HIV or has a partner with an STI

- Condom use, since using condoms correctly and every time when engaging in sexual activity will reduce HIV transmission risk as well as that of other STIs (see box below)

- For women who are unable to convince their partners to use a condom, assessing other barrier methods

- HIV testing, both for the patient and their partner(s)

- Screening and treatment for STDs, due to the shared risk factors for HIV and other STDs

- Stopping injection drug use, or if unable to stop injecting drugs, using only sterile drug injection equipment and rinse water and never sharing equipment with others

- Circumcision, which has demonstrated efficacy in reducing risk among heterosexual men

For people who inject drugs, additional risk reduction interventions can include:

- Voluntary opioid substitution or buprenorphine-naltrexone therapy and participation in needle exchange programs, which has been found to decrease illicit opioid use, injection use, and sharing injection equipment

- Participating in needle exchange or supervised injection programs, which have been found to decrease needle reuse and sharing and to increase safe disposal of syringes and more hygienic injection practices

(HIV.gov, 2023f)

CONDOMS AND THEIR CORRECT USE

To reduce the risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, a male (external) condom or a female (internal) condom for each sexual contact can be used. A male condom is a thin layer of latex, polyurethane (plastic) worn over the penis during sex. A female condom is a thin pouch made of synthetic latex designed to be worn in the vagina during sex. Condoms provide the best protection against HIV.

Do’s of condom use include:

- Do use a condom every time you have sex.

- Do put on a condom prior to having sex.

- Do read the package and check the expiration data.

- Do make sure there are no tears or defects.

- Do store condoms in a cool, dry place.

- Do use latex or polyurethane condoms.

- Do use water-based or silicone-based lubricant to prevent breakage.

Don’t’s of condom use include:

- Don’t store condoms in a wallet, as heat and friction can damage them.

- Don’t use nonoxynol-9 (a spermicide), which can cause irritation.

- Don’t use oil-based products like baby oil, lotion, petroleum jelly, or cooking oil, as they may cause the condom to break.

- Don’t use more than one condom at a time.

- Don’t reuse a condom.

(CDC, 2022f)

Antiretroviral-Based Prevention Strategies

In addition to behavioral strategies, antiretroviral-based strategies have proven highly effective in preventing and reducing HIV transmission.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is for adults who are not infected by HIV but who are at high risk of becoming infected. As a part of PrEP, ART medication is taken consistently every day to reduce the risk of HIV infection through sexual contact.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves taking ART medication to prevent HIV infection after a recent exposure. PEP must be started within 72 hours after a possible exposure and taken daily for 28 days (CDC, 2023e).

For couples in which one is HIV infected and the other uninfected (i.e., serodiscordant), recommendations include:

- Initiation of ART in the infected partner in order to prevent transmission to the uninfected partner; PrEP for the uninfected partner

- Continued use of condoms even when the infected partner has achieved viral suppression and the risk of HIV transmission is negligible, in order to reduce the risk of STD transmission and in case there is a failure in viral suppression

The risk of transmitting HIV from mother to child can be 1% or less if the mother takes HIV treatment as prescribed throughout pregnancy and delivery and the baby is given HIV medications for 2–6 weeks following birth. If the mother’s viral load is not low enough, a cesarean delivery can help prevent HIV transmission. Antiretroviral treatment also can reduce the risks of transmitting HIV through breast milk to less than 1% (CDC, 2023f).

Reducing Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens

In the United States from 1985 to 2013, a total of 58 confirmed and 150 possible cases of occupational transmission of HIV were reported. Only one of those confirmed cases occurred after 1999. Of the 58 confirmed cases, 49 resulted from a percutaneous cut or puncture. From 2000 onward, occupationally acquired HIV infection in the United States has become exceedingly rare, a finding that supports the efficacy of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) (Spach & Kalapila, 2023).

UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS AND STANDARD PRECAUTIONS

Universal Precautions were introduced and then mandated by OSHA in the early 1990s to protect both patients and healthcare staff members. The CDC expanded the concept of Universal Precautions by incorporating major safeguard features of the past into a new set of safety measures. These expanded measures are termed Standard Precautions. Regardless of a patient’s infection status, Standard Precautions must be used in the care of all patients to protect staff from the elements of blood, any body fluids, and secretions and excretions. These precautions include diligent hand hygiene and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (Broussard & Kahwaji, 2022; OSHA, 2021).

EMPLOYER PROTOCOL FOR MANAGING OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURES

If a healthcare worker experiences an HIV exposure in the workplace, the person should follow OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030), which requires employers to make immediate confidential medical evaluation and follow-up available at no cost to workers who have an exposure incident. Management of exposure requirements include:

- Initial management. The first response is to cleanse the area thoroughly with soap and water. For punctures and small lacerations, the area is cleaned with alcohol-based hand hygiene. Exposed mucous membranes are irrigated copiously with water or saline.

- HIV testing. Healthcare personnel should immediately report a possible exposure to the occupational health department so the source patient can be screened for HIV as soon as possible.

- Offering post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP):

- If the source has known HIV infection

- When the HIV status of the source patient is unknown, while awaiting HIV testing results, particularly if the source patient has symptoms consistent with acute HIV infection or is at high risk for HIV infection

- If the source cannot be identified

CONCLUSION

Despite the passage of time and advances in prevention and treatment, HIV/AIDS continues to affect many people around the world. Today’s younger people are living in a time when the disease is known to be controllable, and they may have limited knowledge about the history of HIV/AIDS and a lesser sense of urgency or concern about it. However, the public’s attitude toward the populations that are currently in the forefront of the epidemic remains one of stigmatization.

In the medical field, research has produced ever more effective drugs that slow the disease but do not stop it. No vaccine has proven effective in preventing HIV, and so the epidemic continues to spread, primarily among those high-risk persons living in disadvantaged and marginalized groups: the poor, people of color, people in prison, people who inject drugs, people who exchange sex for money or goods, and men who have sex with men. Many do not realize they are infected and may unknowingly transmit the virus to others.

Healthcare professionals have a vital role in meeting the goals for elimination of new HIV infections. These are built on the following key strategies:

- Educating patients, families, and communities about prevention

- Diagnosing all individuals with HIV as early as possible

- Treating people with HIV rapidly and effectively to achieve sustained viral suppression

- Preventing new HIV transmissions by using proven interventions, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Providing compassionate and nondiscriminatory healthcare to those who have contracted this life-impacting disease

RESOURCES

HIV and AIDS (Office on Women’s Health)

HIVinfo (National Institutes of Health)

HIV tests (CDC)

REFERENCES

NOTE: Complete URLs for references retrieved from online sources are provided in the PDF of this course.

Agyeman-Yeboah J, Ricks E, Williams M, Jordan P, & Ham-Baloyi W. (2022). Integrative literature review of evidence-based guidelines on antiretroviral therapy adherence among adult persons living with HIV. JAN, 78(7), 1909–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15245

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). (2021). HIV/AIDS-related cancer: Introduction. https://www.cancer.net

Be in the KNOW. (2023b). HIV and people who use drugs. https://www.beintheknow.org

Beyrer C. (2021). A pandemic anniversary: 40 years of HIV/AIDS. The Lancet, 397(10290), 2142–3. https://www.thelancet.com

Bokhari A. (2022). Antiretroviral therapy (ART) in treatment-naïve patients with HIV infection. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com

Broussard I & Kahwaji C. (2022). Universal precautions. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023c). STDs and HIV—CDC detailed fact sheet. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023e). Protect others if you have HIV. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023f). HIV and perinatal transmission: Preventing perinatal HIV transmission. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022a). Statistics overview. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022b). About HIV. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022e). HIV testing. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022f). Condom effectiveness. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021a). AIDS and opportunistic infections. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021b). HIV and injection drug use. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021e). HIV infection: Detection, counseling, and referral. https://www.cdc.gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021f). STI and HIV infection risk assessment. https://www.cdc.gov

Cohen M. (2022). HIV infection: Risk factors and prevention strategies. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Felson S. (2022). How HIV case managers can help you. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com

Gardland J. (2023). Patient monitoring during HIV antiretroviral therapy. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

HIV.gov. (2023b). Symptoms of HIV. https://www.hiv.gov

HIV.gov. (2023c). FDA-approved HIV medicines. https://hivinfo.nih.gov

HIV.gov. (2023e). Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov

HIV.gov. (2023f). Preventing sexual transmission of HIV. https://www.hiv.gov

HIV.gov. (2022a). How is HIV transmitted? https://www.hiv.gov

HIV.gov. (2022b). Where can you get tested for HIV? https://www.hiv.gov

HIV.gov. (2022c). Payment for HIV care and treatment. https://www.hiv.gov

International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (IAPAC). (2021). https://www.iapac.org

Latifi F. (2021). The pain gap: Why women’s pain is undertreated. HealthWomen. https://www.healthywomen.org

Mayo Clinic. (2022). HIV/AIDS. https://www.mayoclinic.org

Mental Health America (MHA). (2023). HIV/AIDS and mental health. https://www.mhanational.org

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2023). Update to clinical guidelines for infant feeding supports shared decision making: Clarifying breastfeeding guidance for people with HIV. https://www.hiv.gov

Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). (2021). Standard vs. Universal Precautions. https://www.oshamanual.com

Pahuja M, Merlin J, & Selwyn P. (2023). Issues in HIV/AIDS in adults in palliative care. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Pebody R. (2021). What is the window period for HIV testing. https://www.aidsmap.com

Pieper A & Teisman G. (2023). Overview of neuropsychiatric aspects of HIV infection and AIDS. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Pollack T & Libman H. (2023). Primary care of adults with HIV. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Qureshi S. (2021). HIV and nutrition. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com

Reilly K. (2022). HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com

Rivera D. (2020). Pediatric HIV infection. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com

Sarno E, Swann G, Hall C, et al. (2022). Minority stress, identity conflict, and HIV-related outcomes among men who have sex with men, transgender women, and gender nonbinary people of color. LGBT Health, 9(6). https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2021.0401

Sax P. (2022). Acute and early HIV infection: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Skidmore College. (2023). HIV risk assessment questionnaire. https://www.skidmore.edu

Spach D & Kalapila A. (2023). Occupational postexposure prophylaxis. National HIV Curriculum. https://www.hiv.uw.edu

St. Maarten AIDS Foundation. (2023). Knowledge is power, get informed. https://www.sxmaidsfoundation.org

Tsoi B, Fine S, McGowan J, et al. (2022). HIV testing. Johns Hopkins University. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Tufts Medical Center. (2022). HIV infection from blood transfusions. https://hhma.org

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (USDHHS). (2021). Pregnancy and HIV. https://www.womenshealth.gov

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). (2022). Complementary and integrative therapies for HIV. https://www.hiv.va.gov

Watson S. (2022). The body: What are the chances of getting HIV from one exposure? TheBody. https://www.ihv.org

Wood B. (2023). The natural history and clinical features of HIV infection in adults and adolescents. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). HIV testing and counseling. https://www.emro.who.int/asd/about/testing-counselling.html

Wyatt C & Fisher M. (2023). HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Zachary L. (2023). Management of health care personnel exposed to HIV. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com

Customer Rating

4.9 / 983 ratings