Obesity in America

Management and Treatment in Children, Adolescents, and Adults

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

The United States is in an obesity epidemic. This course focuses on prevention for overweight and obesity. Often, the disease starts in childhood, continues through adolescence, and remains prevalent in adulthood. This continuing education course highlights the comorbidities and consequences and explains the effects of anti-obesity stigma. Strategize with your patients to prevent, manage, and treat this condition successfully.

Note: This course is also available as part of a package. See Nursing CEU Bundle - 30 ANCC Hours

Course Price: $47.00

Contact Hours: 9

Pharmacotherapeutic Hours: 0.25

Course updated on

July 1, 2025

"This was extremely well presented, and I gained more understanding of the topic." - Elizabeth, RN in New Hampshire

"Great course! Information I can use both professionally and personally." - Patricia, OT in Missouri

"Excellent information for me to share in both my professional and personal life. Thank you!" - Rebecca, RN in California

"Thank you for presenting this material with such compassion and deep knowledge of the plight and physical challenges of obese patients." - Barbara, RN in North Carolina

Obesity in America

Management and Treatment in Adults, Children, and Adolescents

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this course, you will have increased your knowledge about obesity, including its prevalence, consequences, contributing factors, interventions, and approaches to prevention and treatment. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Describe the prevalence and impact of overweight and obesity in U.S. adults, children, and adolescents.

- Examine the pathogenesis and etiology of overweight and obesity.

- Discuss the comorbidities and consequences of obesity.

- Explain the psychosocial effects of stigma and weight bias.

- Describe components of assessment for overweight or obesity.

- Summarize strategies for management and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults, children, and adolescents.

- Discuss considerations in caring for the bariatric patient.

- Outline ways to prevent overweight and obesity in all age groups.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- What Causes Obesity?

- Comorbities and Consequences of Obesity

- Assessing for Overweight and Obesity

- Management and Treatment of Obesity in Adults

- Management and Treatment of Obesity in Children and Adolescents

- Caring for the Bariatric Patient

- General Strategies for Overweight and Obesity Prevention and Advocacy

- Conclusion

- Resources

- References

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization, in 2022, 1 in 8 people in the world were living with obesity. Worldwide, adult obesity has more than doubled since 1990, and adolescent obesity has quadrupled. Once considered a problem only in high-income countries, middle-income countries now have among the highest prevalence of overweight and obesity worldwide. Obesity is now recognized as one of the most important public health problems facing the world today (WHO, 2024; World Obesity, 2024).

The fundamental basis for overweight and obesity is a chronic energy imbalance that results from consuming more calories (diet) and expending less energy (physical activity). The cause of obesity, however, is multifactorial and includes an obesogenic environment, psychosocial factors, and genetic variants.

At the same time, the lack of an effective health system response to identify excess weight gain and fat deposition in their early stages is aggravating the progression to obesity with profound social, economic, and health implications for individuals and communities (WHO, 2024).

Defining Obesity

Obesity is defined by the Obesity Medicine Association (2023b) as:

A chronic, relapsing, multifactorial, neurobehavioral disease, wherein an increase in body fat promotes adipose tissue dysfunction and abnormal fat mass physical forces (mechanical stressors and pressures), resulting in adverse metabolic, biomechanical, and psychosocial health consequences.

The American Medical Association considers obesity a disease with multiple pathophysiologic aspects requiring a range of interventions to advance obesity treatment and prevention. The recognition of obesity as a disease allows for research interventions to prevent obesity and implement evidence-based treatments for those affected by obesity (OMA, 2023b; ASMBS, 2024a).

A disease is defined as “any harmful deviation from the normal structural or functional state of an organism, generally associated with certain signs and symptoms and differing in nature from physical injury” (Scarpelli et al., 2025).

Some have countered classifying obesity as a disease by saying that obesity is a risk factor for disease but not a disease itself. By such reasoning, however, a condition such as hypertension should not be classified as a disease. Hypertension, however, is a cardiovascular disease, a chronic disease that can lead to other serious conditions.

Arguments made by those who consider obesity to be a disease include:

- Genes may play a role, as well as other diseases or disorders, such as hypothyroidism, Cushing’s disease, and polycystic ovarian syndrome.

- Taking certain medications for other health conditions can lead to weight gain (e.g., antidepressants).

- Each person has their own base metabolic rate, so for two people who are the same height and eat the same diet, one may have obesity while the other does not.

- Some aspects of obesity are preventable; however, it is known that some people may make appropriate changes in diet and exercise yet still be unable to lose significant amounts of weight.

- Obesity is a complex, multifactorial disease scientifically shown to be brought on and sustained by many factors both within and beyond the individual’s control.

Arguments made by those who do not consider obesity to be a disease include:

- There is a lack of diagnostic criteria. There are no characteristic or unique symptoms, and obesity does not always lead to the same body function impairments.

- There are no indexes and standards for obesity measurement; weighing more does not always mean obesity is present.

- Obesity affects the body in many ways and may increase risk of medical conditions such as heart disease and diabetes. However, not everyone with obesity develops health challenges or symptoms, and not everyone with health challenges has obesity.

- Defining obesity as a disease may foster a culture of personal irresponsibility.

(Silva, 2024)

DETERMINING OBESITY

Among several classifications and definitions for degrees of obesity, the following is widely used:

| Classification | Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| (Hamdy, 2025) | |

| Overweight | 25–29.9 |

| Obesity class 1 | 30–34.9 |

| Obesity class 2 | 35–39.9 |

| Obesity class 3 (also called severe, extreme, or massive obesity) |

≥40 |

However, while BMI has been useful for assessing population-level trends, it is not necessarily an accurate measure of obesity at an individual level. It does not measure body fat directly and cannot distinguish between fat, muscle, and bone. (See also “Calculating Body Mass Index” later in this course.)

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans are a special type of X-ray that can estimate the amount of fat tissue a person has.

Bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) is a measurement of impedance of the body to a small electric current. Fat, muscle, and bone have different conductive properties, allowing for estimation of body fat percentage.

MRI estimated volume rather than the mass of adipose is currently an accurate and viable approach for estimating intra-abdominal adipose tissue.

In adults, waist circumference or waist–hip ratio is independently associated with morbidity after adjustment for relative weight (Sampson, 2023).

Scope of the Problem

GLOBALLY

A 2024 report by the NCD Risk Factor Collaboration estimates that more than one billion people in the world are now living with obesity, nearly 880 million adults and 159 million children and adolescents ages 5–19 years (World Obesity, 2024). In 2024, American Samoa had the highest obesity rate globally (80.2%), and Ethiopia had the lowest (1%) (World Population Review, 2024).

IN AMERICA

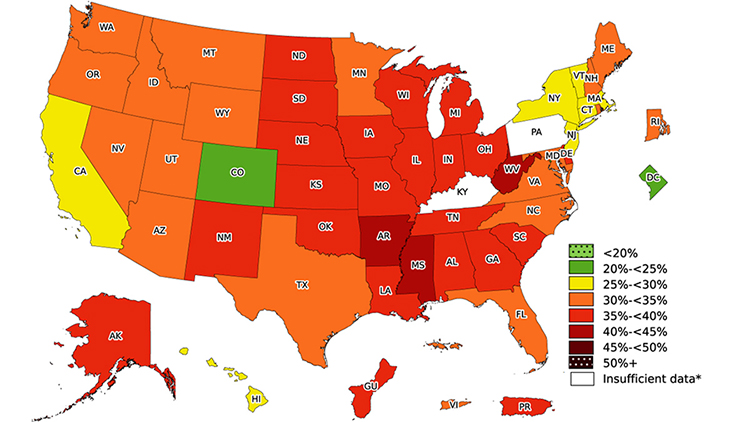

CDC data show that adult obesity prevalence in America remains high. In 2023, at least 1 in 5 adults and 1 in 5 children and adolescents in each state were found to be living with obesity. The states with the highest rates of obesity included West Virginia (41.2%), Mississippi (40.1%), and Arkansas (40%). In 23 states, more than 1 in 3 adults has obesity (CDC, 2024a).

Prevalence of self-reported obesity among U.S. adults by state and territory, 2023. (Source: CDC, 2023a.)

Data from 2021 to 2023 indicates that obesity affects some population groups in the United States more than others:

- By race/ethnicity:

- Asian adults do not have an obesity prevalence at or above 35% in any state.

- In 16 states, White adults have an obesity prevalence at or above 35%.

- In 20 states, American Indian or Alaska Native adults have an obesity prevalence at or above 35%.

- In 34 states, Hispanic adults have an obesity prevalence at or above 35%.

- In 38 states, Black adults have an obesity prevalence at or above 35%.

- By age:

- Prevalence of obesity among adults was 40.3% in 2023.

- Prevalence of severe obesity in adults was 9.4% in 2023 and higher in adults ages 20–39 (9.5%) and 40–59 (12.0%) than in adults 60 and older (6.6%).

- In 2023, 1 in 5 American children were classified as having obesity:

- 12.7% among ages 2–5

- 20.7% among ages 6–11

- 22.2% among ages 12–19

- By sex:

- The prevalence of obesity was 39.2% in men and 41.2% in women. No significant differences between men and women were seen overall or in any age group.

- The prevalence of “severe” obesity in adults was 9.4% and was higher in women than men for each age group.

- Among men, prevalence was highest in those ages 40–59; among women, the prevalence was higher in those ages 20–39 and 40–59 than in those ages 60 and older.

- By educational level: Both men and women with college degrees had lower obesity prevalence compared with those who have less education.

- By income:

- Of those with incomes less than $15,000, 37.4% had obesity.

- Of those with an income of $75,000 or greater, 29.4% had obesity.

- Among non-Hispanic Black men, the obesity rate is higher in the highest income level.

- Among non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic women, obesity prevalence is lower in the highest income group compared to middle- and lower-income groups.

- Among non-Hispanic Black women, there was no significant difference in obesity prevalence based on income level.

(CDC, 2024a; Lyun et al., 2024)

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACTS

The economic burden of obesity remains a paramount global concern due to its escalating prevalence, which imposes substantial pressures on healthcare systems, hampers productivity, and detracts from quality of life. Obesity has a strong impact on the global economy, with total costs estimated to range from 0.05% to 2.24% of a country’s gross domestic product. World Obesity (2024) estimates that the annual global economic impact of obesity will surpass $4 trillion by 2035. Studies to date have identified at least four major categories of economic impact linked to the problem of obesity: direct medical costs, productivity costs, transportation costs, and human capital costs.

Because obesity is linked with higher risk for health conditions such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, coronary heart disease, stroke, asthma, and arthritis, direct medical spending on diagnosis and treatment of these conditions also increases with rising obesity levels. It has been estimated that in 2019 the annual medical cost of obesity was nearly $173 billion, with medical costs $1,861 higher for those with obesity compared to those at a healthy weight.

In addition to the direct medical costs, indirect costs include negative effects on productivity. The productivity costs of obesity are well-documented, with widespread agreement that such costs are substantial. Productivity costs are increased due to absenteeism for obesity-related reasons and decreased productivity of employees while at work.

Other categories of productivity costs include:

- Premature mortality and loss of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs)

- Higher rates of disability benefit payments

- Increase in disability insurance premiums

The cost of transportation is another economic issue of concern. Obesity requires larger vehicles and more fuel, leading to greater greenhouse gas emissions. The cost of airline fuel is also significant, with calculated weight gain shown to require approximately 350 million extra gallons of jet fuel in a year (Dietz, 2023a; Sweis, 2024). Beyond economic costs, obesity can lead to social stigma and discrimination in employment and social situations. Despite decades of research that demonstrate the dominant influence of genetic and environmental factors in the development of obesity, obesity continues to be viewed as a result of individual decision-making, leading to harmful assumptions about the lifestyles and characters of people with obesity (Westbury et al., 2023).

WHAT CAUSES OBESITY?

There are many factors involved in the etiology of obesity. These factors result in a chronic positive energy balance regulated by a complex interaction between endocrine tissues and the central nervous system. Possible components and contributors for the development of obesity include:

- Metabolic factors

- Genetic factors

- Level of activity

- Endocrine factors

- Race, sex, and age factors

- Ethnic and cultural factors

- Socioeconomic status

- Dietary habits

- Smoking cessation

- Pregnancy and menopause

- Psychological factors

- History of gestational diabetes

- Lactation history in mothers

- Gut microbiome characteristics

- Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the environment and food supply

Studies suggest that the genetic contribution to adult obesity is 40%–70% in most individuals. If a young person has one biologic parent with obesity, the risk of obesity is increased three to four times compared with those who do not have a parent with obesity.

Rare forms of obesity result from certain genetic abnormalities, including:

- Prader-Willi Syndrome

- Bardet-Biedl syndrome

- Monogenic obesities:

- Melanocortin 4 receptor deficiency (the most common)

- Leptin and leptin receptor deficiency

- Proopiomelanocortin (PMC) deficiency

It is also believed that obesity has an infectious component, and several studies have linked obesity to infection with adenovirus 36 (ADV36). This adenovirus interferes with insulin resistance and cytokine production in individuals with obesity.

Individuals who are overweight or have obesity have altered circulatory levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor (formerly referred to as TNF), C-reactive protein (CRP), and IL-18. Resistin and visfatin are suggested as important pro-inflammatory mediators that interfere with the regulation of insulin sensitivity (Perreault & Rosenbaum, 2024; Khanna et al., 2024; Hamdy, 2025; Sanches et al., 2023).

Excess Adipose Tissue

Obesity is characterized by the accumulation and inflammation of excessive body fat (adipose tissue). Adipose tissue is the primary storage site for excess energy and is classified as an endocrine gland that plays many roles in metabolism, including modulating energy expenditure, appetite, insulin sensitivity, bone metabolism, reproductive and endocrine functions, inflammation, and immunity.

Adipose tissue makes and releases the hormone leptin, which acts on the brainstem and hypothalamus to help inhibit hunger and regulate long-term balance between food intake and energy expenditure. Because the amount of leptin in the blood is directly proportional to the amount of adipose tissue, having excess adipose tissue results in high levels of leptin.

This leads to leptin resistance, wherein the brain no longer responds normally to leptin. Since the brain is constantly being stimulated by leptin, there is an absence of the sensation of feeling full, causing one to eat more even though the body has enough fat stores. The seeming lack of leptin also causes the body to enter starvation mode (adaptive thermogenesis) and to lower the basal metabolic rate in order to conserve energy, resulting in the use of fewer calories at rest and worsening weight gain (Cleveland Clinic, 2022a).

The distribution of adipose tissue in the body can vary depending on sex. In general, men accumulate fat around the waist, and women accumulate more fat around the hips. Geneticists have found distinct regions in the human genome that are associated with fat distribution, and knowledge of their precise functions could provide insights into the biologic mechanisms underlying obesity (Rogers, 2024).

Genetics

A growing body of evidence suggests that obesity is genetic. Between 200 and 500 specific genes have been linked to the disease, and twin studies have supported that hypothesis. Several measures of obesity show a high rate of heritability.

Studies of adiposity between twins, adoptees, and their parents, as well as within families, all suggest the existence of genetic factors in humans with obesity. The heritability of adiposity estimated from twin studies is high, ranging from 40% to 75%, with only slightly lower values in twins raised apart compared to those raised together. Responses to overfeeding and underfeeding, energy expenditure, food choices, hunger, and satiation have all been shown to be significantly heritable (Perreault & Rosenbaum, 2024).

Obesity is classified as either monogenetic, polygenetic, or syndromic based on its genetic contribution.

Monogenetic obesity involves rare mutations of one gene, typically causing severe early-onset obesity with abnormal feeding behavior and endocrine disorders.

Polygenetic (also known as common obesity) arises from interactions between multiple gene variants and elements in the environment that may facilitate development of obesity. Sixty percent of genetic cases fit into this category. Studies on polygenic obesity have found over 900 genetic variants associated with obesity.

Syndromic obesity is associated with intellectual disability, dysmorphic features, or abnormalities affecting different organs and systems. These include:

- Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)

- Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS)

- Pseudohypoparathyroidism (PHP)

- Alström syndrome (ALMS)

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS)

- Carpenter syndrome

- Cohen syndrome

- Down syndrome

(NIH, 2024a, NIH, 2024b; Kalinderi et al., 2024; NORD, 2023a, NORD 2023b)

Epigenetics and Obesogens

Epigenetics is the study of how environmental factors and behaviors can alter gene function. Epigenetic changes are reversible and do not change the sequence of DNA bases, but they can change how the body reads a DNA sequence and subsequently how proteins are produced. An environmental factor can result in an epigenetic change by adding a chemical (a methyl group) to DNA that turns genes off.

Obesogens are chemicals in common products that may contribute to obesity. Obesogens are endocrine disruptors that play a role in metabolism and that may affect human hormones, changing the way a body makes, stores, and uses fats. These chemicals do not directly cause obesity, but they may increase susceptibility to weight gain.

Research indicates that there are several ways obesogens affect the body, including:

- Increasing fat cells. In some instances, the new cells may be unusually large, allowing for more fat to build up in the body.

- Blocking fat burning so that fat cells cannot release stored fat.

- Altering appetites by affecting the hypothalamus, which releases hormones that signal hunger and others that signal satiety, leading to a tendency to compulsively eat and not stop even though the person is no longer hungry.

The most sensitive time for exposure to obesogens is during early development—as a fetus or during the first years of life—when the body’s weight-control mechanisms are being developed (Ratini, 2023; NIEHS, 2024a).

CHEMICAL OBESEGENS

- Flame retardants: used in many electronics, furniture, and building materials and linked to endocrine disruption and thyroid dysfunction

- Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): present in products and materials produced before 1979 and linked to increased risk for cancer, infection, diabetes, heart attack and stroke, and difficulties with learning and memory

- Tobacco smoke, which contains a mix of more than 7,000 chemicals

- Outdoor air pollution

- Tributyltin (TBT), a pesticide additive, banned in 2008, due to possible harmful effects on the immune and neurological systems and embryos in mammals

- Phthalates: found in many consumer products and associated with increased risk of cancer, asthma and allergies, and learning attention and behavioral difficulties in children

- Bisphenol A (BPA): used primarily in the production of polycarbonate plastics and epoxy resins and linked to childhood obesity

- Many types of pesticides

Endocrine Diseases

Along with the hormones released from adipocytes, other hormones secreted by the endocrine system can be involved in conditions that result in obesity. These endocrine conditions can include:

- Hypothyroidism

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome

- Hyperandrogenism in females

- Cushing’s syndrome

- Hypothalamic disorders

- Hypogonadism in males

- Growth hormone deficiency

- Pseudohypoparathyroidism

The mechanisms for the development of obesity vary based on the endocrine condition. Hypothyroidism, for example, involves an accumulation of fluid-retaining hyaluronic acid, resulting in excess retention of salt and water, which is associated with changes in body weight and composition. It also affects body temperature, energy expenditure, food intake, and glucose and lipid metabolism (ATA, 2024).

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), the most common endocrine disorder in women, is marked by some combination of irregular periods, an excess of androgen, and polycystic ovaries (enlarged and lined with follicles). PCOS causes weight gain, and obesity can also exacerbate the effects of the condition (TGH, 2025).

Cushing’s syndrome occurs when the body has too much cortisol for a long period of time. This can be due to the body producing too much cortisol or from taking glucocorticoid medications. Most patients with Cushing’s syndrome have obesity due to stimulation of appetite and the effect of glucocorticoids to promote deposition of visceral fat (Mayo Clinic, 2023a).

Hypothalamic Obesity

Hypothalamic obesity specifically refers to excess weight gain that may follow malformation or anatomical injury to the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus affects energy intake by regulating how much is eaten and how much energy is expended. Damage to the hypothalamus disrupts the balance between energy intake and expenditure, leading to increased caloric intake and/or decreased calorie burning, resulting in rapid weight gain, which can be difficult to reverse with currently available treatments (NORD, 2022).

Inflammation and Infection

Obesity influences the immune response, which can lead to susceptibility to infections. Excess adipose tissue causes proinflammatory pathways to be activated and can lead to chronic low-grade inflammation. Macrophages play a key role as the main cellular component of the adipose tissue regulating the chronic inflammation and modulating the secretion and differentiation of various pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Weight gain typically causes hormonal and metabolic changes that lead to an increase in C-reactive protein levels in the blood, which play a role in the body’s innate immune system and is used as a biomarker of inflammation. The resulting inflammation impairs the body’s ability to process insulin, leading to higher glucose levels and liver fat accumulation, which further impairs insulin processing.

Inflammation also appears to play a major role in the development of obesity, increasing the risk for metabolic disease, atherosclerosis, various malignant tumors, and a host of immune-mediated disorders that are due to a chronic, systemic, inflammatory response (Brezinski, 2024; Savulescu-Fiedler et al., 2024).

Chronic Stress

Studies show links between chronic stress and obesity. Stress can cause weight gain by:

- Interfering with cognitive processes such as self-regulation

- Increasing levels of hormones and chemicals involved in hunger, such as leptin and ghrelin

- Causing overindulgence in foods that are high in calories, fat, and sugar

- Disrupting sleep

- Depleting energy levels and causing people to engage in less physical activity

When stress is experienced, the body reacts by releasing the stress hormone cortisol, which triggers the fight-or-flight response. This slows down the digestive processes by diverting blood flow away from the digestive tract and toward the muscles and organs essential for immediate survival. Chronic exposure to cortisol leads to enlarged intestines, resulting in more nutrient absorption and obesity.

High levels of cortisol also interfere with the way the body produces other hormones, including corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). This hormone helps control appetite, so low levels may lead to higher food intake (Mayo Clinic, 2023b; Weber, 2023).

Gut Microbiota

Gut microbiota is a collection of trillions of microorganisms that live within the gastrointestinal tract. These microorganisms include over a thousand species of bacteria as well as viruses, fungi, and parasites. The microbiota produces both short-chain fatty acids that feed the cells in the gut lining and the enzymes needed to synthesize certain vitamins, including B1, B9, B12, and K.

There is overwhelming evidence that the composition of the gut microbiota and its metabolites impact the progression of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Gut microbiota provides crucial signaling metabolites, substances made or used when the body breaks down food, drugs or chemicals, or its own tissues including fat or muscle. This process produces energy and the materials required for growth, reproduction, and maintaining health. It also helps rid the body of toxic substances.

The composition and characteristics of the gut microbiota, as well as the factors affecting their homeostasis, are different between stages of infancy and between infants and adults. Gut microbiota disruption is associated with aging, antibiotic exposure, underlying diseases, infections, hormonal variations, circadian rhythm, and malnutrition, either alone or in combination.

Importantly, gut microbiota metabolites—including those that are biochemically modified by gut bacteria and produced by the host, but also those that are produced by bacteria from dietary components—play a vital important role in the development of obesity and related diseases (Geng et al., 2022; Cleveland Clinic, 2023).

Prenatal Factors

Intrauterine environment can shape the trajectory of weight gain and body fatness throughout the course of life. Three prenatal factors are the mother’s smoking habits, weight gain, and blood glucose levels during pregnancy.

MATERNAL PRENATAL SMOKING

Smoking during pregnancy is associated with increased child overweight independent of maternal prepregnancy weight as well as maternally transmitted and nontransmitted genetic predisposition to adiposity. Avoidance of smoking during pregnancy may help prevent childhood obesity irrespective of the mother–child genetic predisposition (CDC, 2023b; Schnurr et al., 2022).

MATERNAL WEIGHT

The offspring of pregnant women with obesity are at increased risk of developing obesity in childhood and as adults. Having one parent with obesity increases the risk of obesity by two- to threefold; two parents with obesity increases the risk up to 15-fold.

In utero nutritional excess and development in an obesogenic environment may lead to permanent changes of fetal metabolic pathways, raising the risk of childhood and adult diseases, such as hypertension, hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, obesity-increased adiposity, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (Ramsey & Schenken, 2024).

MATERNAL BLOOD SUGAR LEVELS

High blood sugar during pregnancy increases an infant’s risk of being born too large and developing obesity or type 2 diabetes in the future (CDC, 2024b).

Gestational diabetes (GDM) starts when the body is not able to use the insulin it needs during pregnancy, leading to hyperglycemia. Gestational diabetes causes the pancreas to produce more insulin, but it is not able to lower blood glucose levels. The insulin does not cross the placenta to the baby, but glucose and other nutrients do. This gives the infant high blood glucose levels, causing the baby’s pancreas to make extra insulin to process the blood glucose. Since the infant is getting more energy from the extra blood glucose than it needs, the extra energy is stored as fat. In addition, children exposed to gestational diabetes have stronger brain responses to food cues, particularly in reward-processing regions, increasing risk of overeating and obesity (Zhao et al., 2024).

Postnatal Factors

The postnatal environment is just as significant to setting the pace of weight gain throughout life. Modifiable postnatal factors that affect weight in later life include:

- Rate of infant weight gain. Children with accelerated infant growth have an increased risk for being overweight. Children with fast fetal growth and subsequent accelerated infant growth have the greatest risk of being overweight at 5–9 years (Leth-Møller et al., 2024).

- Breastfeeding initiation and duration. A meta-analysis of 17 studies reported that a longer duration of breastfeeding is associated with a lower risk of weight gain in infancy, with each month of breastfeeding reducing the risk by 4% (Masood & Moorthy, 2023). Among infants born in 2019, most (83.2%) started out receiving some breast milk. At 1 month of age, 78.6% were receiving some breast milk. At 6 months, 55.8% of infants received some breast milk, and 24.9% received breast milk exclusively (CDC, 2024c).

- Infant sleep duration. Sleep regulates glucose metabolism and neuroendocrine function. Lack of sleep reduces glucose intolerance, insulin sensitivity, and leptin levels and increases the levels of cortisol and ghrelin (and, therefore, appetite). It has been found that infants who slept fewer than 12 hours a day had double the odds of being overweight by the age of 3 years, compared with infants who slept more than 12 hours a day. If a 3-year-old sleeps less than 10 and a half hours each night, there’s almost double the chance of obesity by age 7. Factors associated with shorter sleep duration included maternal depression during pregnancy, early introduction of solid foods (before 4 months), and infant television viewing (Masood & Moorthy, 2023; DiLonardo, 2024).

Ultraprocessed Foods

Ultraprocessed foods are industrial formulations made mostly or completely from substances (oil, fat, sugar, starch, and protein) extracted from food or derived from hydrogenated fats or modified starches then reassembled to create shelf-stable, tasty, and convenient meals. They can also be synthesized in laboratories with flavor enhancers, colors, and additives to make them highly palatable. These foods typically have five or usually many more ingredients. Ultraprocessed foods currently make up nearly 60% of what the typical adult eats and nearly 70% of what children eat.

Ultraprocessed foods tend to be low in fiber and high in calories, salt, added sugar, and fat. High consumption of these foods has been linked to health concerns, including increased risk of obesity, hypertension, breast and colorectal cancer, and premature death from all causes. Research, however, has not completely identified exactly what it is about this category of food that appears to cause these issues.

A 2019 study was done to compare the ultraprocessed diet to one based on minimally processed foods featuring fruits, vegetables, and unprocessed meats. Participants were served twice as many calories as needed to maintain their body weight and told to eat as much or as little as they wanted. Both diets were nutritionally matched, containing the same total amount of fat, sugar, salt, fiber, carbohydrates, and protein. When eating the ultraprocessed diet as compared to eating the unprocessed diet, participants were found to consume about 500 calories per day more and gained more weight and body fat, putting on an average of two pounds (Valicente et al., 2023; Godoy, 2023).

ULTRAPROCESSED FOODS AND GUT MICROBIOME

Diet has a pivotal role in shaping the composition, function, and diversity of the gut microbiome, with various diets having a profound impact on the microbial community within the gut. Studies have suggested that food processing promotes changes in foods such as inclusion of acellular nutrients, additives, and novel chemicals, which can then impact gut microbiota that promote an inflammatory microbiome.

In addition to differences in gut microbiota, higher ultraprocessed food consumption has been found to be positively related to leptin levels, which is related to leptin resistance. Leptin signals the body that there are sufficient energy stores, reducing hunger. Leptin resistance is associated with proinflammatory conditions, neuroinflammation, and metabolic disorders (Ross et al., 2024).

ADDICTIVE POTENTIAL OF ULTRAPROCESSED FOODS

Preclinical and human studies have demonstrated that repeated intake of ultraprocessed foods triggers addictionlike biologic (e.g., dopaminergic sensitization) and behavioral (e.g., withdrawal, continued use despite consequences) responses, whereas consumption of naturally occurring foods has demonstrated limited or no associations with addiction indicators.

This differentiation has been attributed to ultraprocessed foods sharing pharmacokinetic properties with addictive substances, namely those containing artificially high doses of rewarding ingredients (e.g., added sugars) that are rapidly absorbed by the system. Researchers recently argued that ultraprocessed foods meet the same scientific criteria used to define tobacco products as addictive.

Both addictive drugs and ultraprocessed foods can induce cravings in the same reward area of the brain, as demonstrated by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Reward signals from highly palatable foods may override signals of fullness and satisfaction. Compulsive overeating is a type of behavioral addiction that triggers intense pleasure. Those with food addiction lose control in regard to overeating behavior and spend excessive amounts of time involved with food and overeating or anticipating the emotional effects of compulsive overeating (Zaraska, 2023; Goodman, 2023).

SALT

Throughout evolutionary history, salt has been a vital necessity for survival, and it has been a very rare resource. As a consequence, humans have evolved neuronal pathways for a habitual salt craving, which cannot be controlled. The importance of salt to overall health may explain why salty foods are so tasty and “you can’t eat just one.” Sodium appetite is an important instinctive behavior with high survival value, as there are many physiologic and cellular functions that depend on salt.

Neuronal mechanisms help drive the lust for salt. Neurons in the central amygdala become highly active when salt is being consumed. This area of the brain controls many innate and conditioned behaviors, including appetite-related and feeding behaviors. When we consume salt, the central amygdala is activated and dopamine is released, which triggers the brain’s reward system. This process is part of our evolutionary heritage to ensure our ancestors sought out this essential mineral (Research Features, 2023).

INDUSTRIAL SEED OILS

Industrial seed oils are derived from nuts, legumes, oilseeds, or fruits. They’re made by a chemical process in which these items are bleached, refined, and heated. Seed oils are a type of vegetable oil that come from the seeds of crops and contain high levels of linoleic acid, an e-omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid. Linoleic acid is needed by the human body in small amounts, but the excessive quantities found in seed oils can contribute to chronic diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Seed oils that have moderate to high amounts of linoleic acid include:

- Soybean oil

- Canola oil

- Rapeseed oil

- Corn oil

- Sunflower oil

- Safflower oil

- Grapeseed oil

- Rice bran oil

Oils that are extracted from fruits have low to moderate amounts of linoleic acid:

- Olive oil

- Avocado oil

- Coconut oil

- Palm oil

(H & S Crew, 2024)

When oils (fats) are detected in the upper intestine, the message is carried up the vagus nerve through the hindbrain to the striatum. Foods rich in fat can increase dopamine in the striatum as much as 160% to 200% above normal levels, similar to what is observed with nicotine and alcohol, which produce feelings of pleasure and reward (Yang, 2024).

GLUCOSE AND FRUCTOSE

Excessive sugar consumption is linked to obesity primarily because it contributes to increased calorie intake, often with little nutritional value, and can lead to a build-up of fat in the body. Additionally, sugary drinks and foods can disrupt appetite-control signals and promote weight gain by not providing the same feeling of fullness as solid foods.

There are two main types of dietary sugars, glucose and fructose, with fructose being sweeter than glucose. (Sucrose, or table sugar, is a combination of fructose and glucose.) Both have an identical molecular formula but different structural formulas. Glucose consists of an aldehyde group, while fructose consists of a ketone functional group.

Both glucose and fructose are harmful when consumed in excess. What makes fructose more harmful is the way in which the body metabolizes it. Unlike glucose, which is used by cells as an energy source, fructose is metabolized by the liver, where it promotes synthesis of fat. Some of the fat can lodge in the liver, contributing to fatty liver disease. High fructose consumption is also linked to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and obesity.

In the past, fructose was a rare treat found in honey or seasonal fruit. Today, high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), which is made from cornstarch and contains approximately 55% fructose, is found in most processed foods and sugary drinks (Leech, 2023).

Growing evidence indicates that daily fructose consumption leads to some pathological conditions, including memory impairment. Fructose intake induces neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress. Subsequently, these mechanisms can trigger long-term effects, such as inhibition of neurogenesis, downregulation of trophic factors and receptors, weakening of synaptic plasticity, and long-term potentiation decay. In addition, it significantly affects several functions regulated by the nervous system, such as the sleep–wake cycle, locomotor activity, feeding behavior and energy homeostasis, as well as cognitive impairment (Franco-Pérez, 2024).

NOVA CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

The NOVA classification system, developed by researchers at the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, places all foods into four groups:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

- Meat, poultry, fish, and seafood

- Eggs

- Milk

- Fresh, frozen, or dried fruit

- Leafy and root vegetables

- Grains (brown or white rice)

- Legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas)

- Group 2: Processed culinary ingredients

- Salt (mined or from seawater)

- Sugar (cane or beat)

- Butter and lard (milk and pork)

- Starches from corn and other plants

- Vegetable oil (crushed from olives or seeds)

- Group 3: Processed foods

- Canned or bottled vegetables, fruits, and legumes

- Salted or sugared nuts and seeds

- Salted, cured, or smoked meats

- Fruits in syrup

- Cheeses and unpackaged freshly made breads

- Group 4: Ultraprocessed food and drink products

- Sodas and sweetened drinks, including energy drinks

- Sweet or savory packaged snacks

- Confectionery and industrialized desserts (e.g., ice cream)

- Mass-produced packaged breads and buns

- Cookies, pastries, cakes, and cake mixes

- Margarine and other spreads

- Sweetened breakfast cereal

- Sweetened and flavored yogurts

- Preprepared meat, cheese, pasta, and pizza dishes

- Packaged meatballs

- Poultry and fish nuggets and other reconstituted meat products

- Meat products that contain preservatives other than salt

- Frozen or shelf-stable instant meals

- Instant noodles and instant or canned soups

- Baby formula and other baby food products

- Weight-loss products such as meal replacement shakes and powders

(MacMillan, 2024)

Medications

Weight gain as a result of certain prescription medications is known as iatrogenic obesity. Many commonly used medications list weight gain as a frequent side effect. Research has found that patients taking certain prescription medications gained weight, ranging from a few pounds to 10% or more of their body weight.

Each class of medication may trigger weight gain through different mechanisms. Some stimulate appetite. Others affect metabolic rate, which can result in weight gain despite not changing dietary habits. Some medications influence how the body stores and absorbs sugar and other nutrients.

Weight gain from prescription medications also increases the risk of a multitude of other complications, including metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Medications that can result in weight gain include:

- Antidepressants

- Amitriptyline

- Citalopram

- Sertraline

- Nortriptyline

- Paroxetine

- Anticonvulsants

- Pregabalin

- Gabapentin

- Carbamazepine

- Valproic acid

- Antidiabetics

- Glipizide

- Insulins

- Glyburide

- Pioglitazone

- Antipsychotics

- Olanzapine

- Quetiapine

- Clozapine

- Perphenazine

- Antihypertensives

- Atenolol

- Metoprolol

- Propranolol

- Antihistamine and steroids

- Diphenhydramine

- Prednisone

(Dietz, 2023b)

Insufficient Physical Activity

Physical activity refers to any body movement that burns calories, whether for play or work. Exercise, a subcategory of physical activity, refers to planned, structured, and repetitive activities with the goal of improving physical fitness and health.

Most weight loss occurs from decreasing calories, but the only way to maintain weight loss is to engage in regular physical activity. Regular physical activity is a vital necessity for good health. Physical activity helps to reduce blood pressure and reduce risks for type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, heart attack, stroke, certain cancers, as well as obesity. It can relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety, improve sleep, reduce risk of falling, improve cognitive function in older adults, and maintain a healthy weight.

Despite this recognition of the need for an increase in physical activity, however, recent statistics show that:

- Only 1 in 3 children are physically active every day.

- Less than 5% of adults participate in 30 minutes of physical activity each day, and only 1 in 3 adults receives the recommended amount of physical activity each week.

- Only 35%–44% of adults ages 75 years or older are physically active, and only 28%–34% of adults ages 65–74 are physically active.

- 28% of Americans, or 80.2 million people, ages 6 and older are physically inactive.

- More than 80% of adults do not meet the guidelines for both aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities, and more than 80% of adolescents do not do enough aerobic physical activity to meet the guidelines for youth.

- Nationwide, 25.6% of persons with a disability reported being physically inactive during a usual week, compared to 12.8% of those without disability.

- Children now spend more than seven and a half hours a day in front of a screen (e.g., TV, video games, computer).

- Nearly one third of high school students play video or computer games for three or more hours on an average school day.

- Only six states (Illinois, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New York, and Vermont) require physical education in every grade, K–12.

- Only about 1 in 5 homes have parks within a half mile, and about the same number have a fitness or recreation center within that distance.

(Delta College, 2024)

Obesogenic Environment

The term obesogenic environment describes the sum of all influences on the development of obesity from living conditions and surroundings, including opportunities available in a society or institution that are shaped by its social organization and structure. Obesogenic environments particularly promote physical inactivity and unhealthy eating behaviors (Cunningham, 2024).

BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Neighborhood characteristics play a powerful role in shaping people’s health, and research has demonstrated the particular importance of built environment factors associated with human-made spaces that individuals engage with on a regular basis. This includes physical characteristics such as walkability, presence of sidewalks, walking paths, bike paths, green spaces, and recreational and sports infrastructures that promote physical activity and healthful behaviors, as well as factors like public transportation and zoning regulations that constrain individuals’ food environments (Nguyen et al., 2024).

“SCREEN TIME”

Screens are ubiquitous in today’s environment, and almost everyone’s daily routine includes them, including children. Most American children spend about three hours a day watching television. Despite what is claimed, videos that are aimed at very young children do not improve their development.

Added together, all types of screen time can total five to seven hours each day. Too much screen time increases risk for obesity because:

- Sitting and watching a screen is time that is not spent being physically active.

- TV commercials and other screen ads can lead to unhealthy food choices. Food ads aimed at kids are for products that are high in sugar, salt, or fats.

- Children eat more when they are watching TV, especially if they see ads for food.

Current screen-time guidelines include:

- Children under 2 should have no screen time.

- Limit screen time to 1–2 hours a day for children ages 2 and over.

More than two hours of daily screen time is also associated with decreased executive function, decreased inhibition, increased impulsivity and inattention, cognitive changes, binge eating, and loss of eating behavior control (Bleistein, 2022; NIH, 2023a).

FOOD AND NUTRITION ENVIRONMENT

What people choose to eat plays a large role in determining risk of overweight or obesity. People’s choices are shaped by the world in which they live. In the United States, physical and social surroundings influence what one eats and can make it difficult to choose healthy over unhealthy foods. The food and nutrition environment includes all the factors involved in the ability to access foods: the availability of foods, culture and ethnicity, parenting, marketing, and other significant factors.

Food Availability and Access

In 2023 in the United States, 47.5 million people lived in food-insecure households, including 7.2 million children (USDA, 2025). Food availability and access are predominantly influenced by the local environments, including surrounding neighborhood infrastructure, accessibility, and affordability barriers. Access to grocery stores that carry healthy food options is not distributed equitably across residential and regional areas.

Areas lacking access to affordable healthy foods are called food deserts and are found in:

- Suburban neighborhoods that lack grocery stores that offer health food options

- Rural areas and neighborhoods where the nearest grocery stores are too far away to be convenient or accessible

- Neighborhoods that are comprised of a majority of racial or ethnic minorities

- Areas, rural or urban, with a higher percentage of residents experiencing poverty

Urban, suburban, and rural areas can also be overwhelmed with stores that sell unhealthy calorie-dense and inexpensive “junk” foods, including soda, snacks, and other high-sugar foods. This is known as a food swamp. Presence of food swamps is a predictor of obesity, particularly in communities where people have limited access to their own or public transportation and experience the greatest income inequality.

Obesity rates are higher in schools that have nearby access to a greater number of fast-food restaurants and lower in schools with access to small grocery stores and upgraded convenience stores participating in initiatives to improve healthful offers. Schools that offer unhealthier items experience a faster increase in obesity rates over time.

Community-level efforts that have successfully improved children’s food environments include more available healthier reimbursable meals and a la carte options available in schools and convenience stores participating in community initiatives shown to carry healthier foods (Ohri-Vachasapti et al., 2023).

Transportation to grocery stores with affordable prices is critical to food-insecure households. It is challenging to use a combination of public transit and walking to go grocery shopping for several reasons. First, grocery bags can be heavy and hard to carry on buses, transfer may be required, and wait times can be long depending on when shopping is done. In addition, the built environment around grocery stores is often not pedestrian friendly.

Food affordability is another element in choosing where one can shop (Wainer et al., 2023).

Race/Culture/Ethnicity and Diet

In the United States, more than 1 in 5 children have overweight or obesity. Black and Latino children are disproportionately affected, with both having higher prevalence and incidence rates of overweight and obesity than their White counterparts. Systemic inequalities, such as racial discrimination and unequal access to education and healthcare, can perpetuate the cycle of poverty and food insecurity within marginalized ethnic groups. These structural barriers create additional challenges for individuals and families in accessing nutritious food.

Culture affects the circumstances in which we eat, the types of food we eat, whom we eat with, the times of the day that we eat, and the quantities we eat. Food is culture and presents an everyday actualization of one’s ethnic identity. Food contains childhood memories, religious meaning, and connections to one’s origins.

One key aspect of the connection between ethnicity and food insecurity lies in the cultural and dietary practices of different ethnic groups. Cultural traditions, beliefs, and preferences often shape the types of foods consumed within a community. These practices can influence food access and affordability, as traditional or culturally significant foods may be more expensive or less readily available in certain area.

Immigrant communities may face challenges in accessing the ingredients necessary for their traditional dishes, leading to a sense of food insecurity. Additionally, dietary restrictions or preferences based on religious or cultural beliefs can further exacerbate the issue. These factors can limit the options available to individuals and contribute to disparities in food security across different ethnic groups.

Socioeconomic factors play an important role in understanding the connections between ethnicity and food insecurity. Research has consistently shown that certain ethnic groups are more likely to experience poverty and lower income levels, which directly impact their ability to afford an adequate diet. Economic disparities, such as wage gaps and limited job opportunities, can contribute to higher rates of food insecurity among specific ethnic communities (Easy Sociology, 2024).

Family Mealtimes and Parental Feeding Styles

Studies have found that the influence of family mealtimes is correlated with improved dietary intake and healthier weight status. Family meals may contribute to the development of healthy eating habits within the family and may act as a powerful preventative factor in reducing child obesity rates. In the context of family meals, parents provide an important social referencing role and example for their children to learn healthy and appropriate mealtime behaviors that could help them lower their risk for obesity across their development into adolescence and adulthood (Jones et al., 2023).

Parental feeding practices are goal-oriented food-specific behaviors or actions carried out by parents either intentionally or unintentionally that affect their child’s attitudes, behaviors, or beliefs toward food.

Parental feeding style affects children’s eating behaviors. Feeding styles are determined by a combination of demandingness and responsiveness. Demandingness refers to the degree to which a parent encourages a child to eat, while responsiveness refers to the way in which the parent encourages the child to eat, whether in a responsive or non-responsive manner. Parental feeding styles reflect the overall attitude and emotional climate characterizing eating occasions and reflect differences in parental demandingness and responsiveness. Feeding styles include:

- Authoritative feeding style is characterized by high demand and high response and is defined as reasonable nutritional demands in conjunction with sensitivity toward the child. This style is generally considered to be the best approach to prevent childhood obesity, as it has been associated with lower intake of snack foods and better dietary quality in meals.

Three negative feeding styles have been found to be linked to overweight and obesity. These include:

- Authoritarian (as opposed to authoritative) style uses strict rules, high standards, and punishment to regulate a child’s behavior. Authoritarian style involves coercive control and shows low responsiveness to the child’s wishes. It involves low support for child autonomy in eating and shows little trust in a child’s hunger/satiety signs. Example: A child cleans her plate even though she is full in order to please her parents. Effect: Ignoring a child’s appetite may lead to loss of ability to regulate internal hunger and fullness cues.

- Permissive/indulgent style involves making few demands, having very few rules and low expectations, using discipline sparingly, catering to the child’s food preferences, and providing a low level of control. This style is often linked with high intake of sweets and high-fat foods. Example: A child has eaten a cookie for dessert and demands more. The parent’s response is, “Okay, you can have as many as you want.” Rewarding is another example of an indulgent style. Example: A parent tells a child at the dinner table, “If you eat all your broccoli, I’ll take you out for ice cream.” Effect: The child tends to become out of touch with what and how much to eat.

- Uninvolved/neglectful style includes low demands and low responsiveness to the child, lack of support, and lack of structure and control. Parents show low sensitivity to their child’s needs and fail to plan and prepare food in a regular, reliable manner, considering food and feeding to be a low priority. This style is not always a conscious choice but can be forced by circumstances, such as single parenting and working late shifts. Example: A child is hungry, but there is no response from the parent to provide a regular meal. Because they consider food and feeding to be a low priority, they have not gone shopping, and therefore no one prepares a meal. Effect: The child becomes preoccupied with food, worried, and anxious, causing over- or undereating (Nelson, 2023).

WORK ENVIRONMENT AND OCCUPATION

The type, hours, and place of work have been recognized as sources of adverse environmental exposures that can lead to overweight and obesity.

- The number of hours spent at work. Research studies show that working long hours on the job is associated with higher body weight, and this is magnified when people work in occupations that are primarily sedentary. For workers in sedentary jobs, every 10 additional work hours was found to be associated with an average weight gain of three to four pounds for men and two pounds for women (Leach et al., 2023).

- Rotating shift work has been identified as a risk factor for overweight or obesity. Working rotating shifts disrupts the body’s natural circadian rhythm, disrupting the body’s internal clock which regulates metabolism and appetite. When disturbed it can lead to hormonal imbalances that may increase risk of weight gain and obesity (Physicians Premiere, 2023).

- Night shift work is associated with a significant increase in waist circumference. Dyslipidemia is significantly associated with night shift workers, which is the result of disruption in the circadian rhythm. Raised proinflammatory markers in night shift workers increases the risk of metabolic syndrome (Ellis, 2023; Bahinipati et al., 2022).

- Blue-collar workers (which may include machine operators, construction workers, public safety workers, and sales/office workers) have a higher risk of obesity. Many of these workers believe that a physically active occupation provides sufficient physical activity for health. In addition, surveys of foods available in work environments have shown that many of the workers in these professions have little access to healthy foods while at work and little access to intervention that would support attempts to change behaviors. Worksite wellness features, such as onsite workout facilities or weight control programs, are lacking in worksites with a high proportion of blue-collar occupations (Crane et al., 2022).

- Work-related stress can exacerbate anxiety and negatively affect diet quality. Studies have shown that work stress is a crucial risk factor for the development of metabolic syndrome, which includes weight gain. Stress-induced hormonal imbalances can lead to dysregulation in carbohydrate metabolism, making further weight gain easier and weight loss more difficult. In addition, behavioral factors, such as comfort food eating or drinking, may exacerbate the effects of work stress on weight (Nuesana, 2024).

FOOD MARKETING

Advertisements for unhealthy foods are everywhere, and marketing to young people to “hook” them on food manufacturers’ products presents a very profitable investment. Food marketing takes advantage of the developmental vulnerabilities of children and adolescents. Adolescent brains are biased toward rewards, and they are more likely to respond to cues in the environment, such as marketing.

Studies from many countries have shown that television marketing of unhealthy foods frequently targets children. Internationally, unhealthy food advertisements are more frequent during children’s typical viewing times, during school holidays, on children’s channels, and around children’s programming.

A wide range of creative advertising strategies are used that are likely to appeal to young people. These include celebrity endorsements, animations, and promotional characters. International studies of television and other media have shown that these creative strategies were more common in the marketing of food to children than to adults.

Product packaging that includes the presence of cartoon characters has been found to influence taste perceptions in young children. In one U.S. study of children ages 4 to 6 years, the children believed a product with a cartoon character tasted better than the same food in a package without the character. In another U.S. study, children ages 3 to 5 years tasted identical pairs of food and drink but felt they tasted better if they were in McDonald’s-branded packaging.

Results from a study on brain activity found that food commercials produced larger brain responses than nonfood commercials in different areas of the brain, including the middle occipital gyrus, which has been shown to consistently respond to drug-related cues compared with nondrug cues. Among children, the right middle occipital gyrus had higher activation in response to food advertising exposure.

The whole occipital lobe plays a role in visual processing of food cues. The fusiform gyrus, which is part of the brain’s visual object recognition system, was found to be one of the main brain regions activated in response to viewing food pictures, as was the posterior cingulate gyrus (OEH, 2023; Arrona-Cardoza et al., 2023).

SLEEP DEPRIVATION

Sleep deprivation influences food selection and eating behaviors, which are mainly managed by the food reward system. Sleep-deprived individuals mostly crave palatable energy-dense foods. Consumption of meals may not change, but energy intake from snacks that are high in sugar and saturated fat are desired, leading to overweight and obesity.

This is due to an imbalance in the hormones ghrelin and leptin that regulate appetite. Leptin makes one feel full, and ghrelin makes one feel hungry. Leptin levels typically rise during sleep, so if a person is not getting adequate sleep, the leptin levels decrease and hunger increases, which can lead to excessive foot intake and weight gain. Likewise, sleep disruptions of any kind can cause an increase in ghrelin, resulting in hunger (Wojeck, 2023).

Sleep deprivation also affects weight by having an impact on physical activity and energy expenditure. Sleep allows muscle tissue time to recover between workouts. Sufficient sleep is also important in having the energy to exercise. Lack of adequate sleep can lead to being less physically active during the day and reduced muscle strength. Sleep deprivation can also affect the safety of exercise, with increased sports injuries reported by those who are sleep deprived (Newsom & Rehman, 2024).

The human body generally runs on a sleep–wake cycle that lasts a little over 24 hours. This is known as the circadian rhythm. These rhythms are mostly the result of exposure to light and darkness, and they affect sleep, body temperature, hormone production, appetite, and other body functions. Insufficient sleep and circadian disruption are important metabolic stressors and are associated with weight gain and obesity. Circadian rhythm disruptions can result from:

- Brain damage or disruption in brain activity

- Damage to the eyes, retinas, or optic nerves

- Jet lag (traveling east advances the sleep cycle and tends to cause more severe jet lag than traveling west, which delays the sleep cycle)

- Working overnight shifts

Historically, eating would occur during daylight hours and sleep during night time hours. Today, this may not always be true. Irregularity in meals, such as eating at inconsistent times, skipping meals, and changing the frequency and number of meals, all influence the circadian clock and metabolism (Johns Hopkins, 2025a; NIH, 2023b; Cleveland Clinic, 2024).

COMORBITIES AND CONSEQUENCES OF OBESITY

Overweight and obesity boost the risk of death by anywhere from 22% to 91%, which is significantly more than previously believed. It is estimated that about 1 in 6 deaths are related to excess weight or obesity (Marshall, 2023).

In Adults

DISEASES AND HEALTH CONDITIONS

Obesity is a systemic issue that affects multiple organ systems and may lead to many diseases and health conditions (see table below).

| Body system | Diseases/conditions |

|---|---|

| (Lim & Boster, 2024; Hamdy, 2025; Perreault & Laferrère, 2024) | |

| Cardiovascular |

|

| Respiratory |

|

| Endocrine |

|

| Central nervous system |

|

| Musculoskeletal |

|

| Gastrointestinal |

|

| Urinary tract |

|

| Reproductive |

|

| Psychiatric/psychological |

|

| Integumentary |

|

| Infections |

|

| Neoplasms |

|

COGNITIVE EFFECTS

Neuroimaging studies have shown structural and functional changes in the brains of individuals with obesity (Saeed et al., 2025).

Obesity is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation throughout the body, including in the brain. This systemic neuroinflammation can dysregulate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, impacting cortisol rhythms and potentially contributing to mood disorders and cognitive impairments. This obesity-induced disruption coupled with changes in cortisol secretion is thought to affect brain structures such as the hippocampus, further influencing cognitive function and potentially increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

Over time, brain cell damage may be secondarily due to an increase in the release of inflammatory cytokines by the adipose tissue that impairs cognitive function. Obesity has also been linked to vascular changes that promote atherosclerosis, and reduced blood flow to the brain can lead to cognitive decline and neurodegenerative changes. Obesity-induced systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation contribute to blood–brain barrier (BB) disruption, leading to various neurological disorders (Feng et al., 2024).

Alterations in gut microbiome composition and function may also play a role in the influence of obesity on executive functions. Excess adipose tissue contributes to a proinflammatory state that promotes growth of pathogenic bacteria over beneficial ones. This dysregulation of the gut microbiota can lead to increased intestinal permeability and further systemic inflammation (Allied Digestive Health, 2024; Wright et al., 2024).

MUSCULOSKELETAL EFFECTS

Overweight and obesity places added force and stress on the body’s joints, especially in high-impact areas such as the knees, hips, and ankles. Research shows that for every one pound of weight gained, there is an additional four pounds of force exerted on the knee joint. Over time this excess strain accelerates breakdown of protective cartilage drastically increasing the risk for developing pain and debilitating conditions like osteoarthritis.

Obesity makes bones more susceptible to cracking or breaking. Carrying extra weight also impacts bone health, increasing the risk for fractures, especially in the spine, wrists, and ankles (CORE Institute, 2024).

In Children and Adolescents

Obesity affects children and adolescents across all age groups, and the increasing prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity is associated with a rise in comorbidities previously considered “adult diseases.” In the United States, close to one third of children over age 2 are overweight or have obesity, and for the first time since the 1900s, life expectancy for children is eroding because of obesity (Martinelli, 2022).

DISEASES AND HEALTH CONDITIONS

Obesity in childhood and adolescence can lead to severe health conditions, including:

Endocrine

- Prediabetes (increases the risk for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus)

- Type 2 diabetes (leads to more rapid progression of diabetes-related complications in later life)

- Metabolic syndrome (a cluster of risk factors for type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis, which includes abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension)

- Hyperandrogenism in females and risk for early-onset polycystic ovary syndrome characterized by hirsutism, menstrual irregularities, acne, acanthosis nigricans, and seborrhea; accelerated linear growth and bone age associated with marked hyperinsulinemia

- Gynecomastia in males related to the stimulating effects of fat on estrogen production

- Central precocious puberty, particularly in girls; earlier attainment of pubertal milestones, menstrual disturbances, polycystic ovary syndrome

- Alteration in thyroid status

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease related to ectopic fat aggregation

Cardiovascular

- Essential hypertension, best assessed using ambulatory blood pressure (BP) monitoring rather than casual office BP measurement

- Dyslipidemia, particularly in those with central fat distribution and increased adiposity, including elevated concentrations of LDL cholesterol and triglycerides and decreased concentration of HDL cholesterol

- Alterations in cardiac structure and function similar to those seen in middle-aged adults, including increased left ventricular mass, increased left ventricular and left atrial diameter, greater epicardial fat, and systolic and diastolic dysfunction

- Cardiac fibrosis and impaired systolic and diastolic function related to abnormal lipid metabolism, including excessive activity of adipocyte cell signaling molecules, as well as oxidative stress and inflammation, which can potentially cause cardiac fibrosis and impaired systolic and diastolic function

- Premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease with endothelial dysfunction of the blood vessels, aortic intima-media thickening, development of early aortic and coronary arterial fatty streaks and fibrous plaques, and increased arterial stiffness

Gastrointestinal

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the most common cause of liver disease in children, resulting in fatty infiltration and inflammation of the liver

- Cholelithiasis (gallstones), with obesity being the most common cause in children (greater for girls than boys) without predisposing conditions, the risk increasing with increasing BMI

- Gastroesophageal reflex disorder and a higher risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma

Pulmonary

- Obstructive sleep apnea (complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep and cessation of air movement despite ongoing respiratory effort)

- Alveolar hypoventilation syndrome (Pickwickian syndrome) during wakefulness, a rare but life-threatening disorder that requires prompt diagnosis and therapy

- Hypoventilation during sleep in the absence of airway obstruction, possibly due to the restrictive ventilator defect caused by abdominal distribution of fat

- Increased predisposition for respiratory infections and bronchial asthma

- Adverse effects on lung and chest mechanics, as well as a reduction in lung compliance

Orthopedic

- Slipped capital femoral epiphysis, typically occurring in early adolescence, related to increased shear forces at the capital femoral growth plate

- Idiopathic genu valgum (commonly called knock-knees), characterized by deviation of the knees toward the midline of the body

- Tibia varus (Blount disease), characterized by progressive bowing of the legs and tibial torsion as a result of excessive abnormal weight bearing, more commonly among individuals with darkly pigmented skin

- Fractures, since bone development is not always able to compensate for excess weight, with the resulting imbalance putting undue stress on developing bones

- Increased risk for joint damage or osteoarthritis in adulthood

- Pain, injuries, and fractures due to obesity-induced biomechanical change in gait pattern and greater joint burdens

- Impaired postural control

- Diminished bone mineral density

Neurologic

- Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri), in which increased intracranial pressure is observed with the absence of a mass, which presents with signs and symptoms of a brain tumor and can result in severe visual impairment or blindness

- Migraine incidence and progression

- Psychosocial

- Depressive conditions

- Eating disorders

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and low self-esteem

- Anxiety, self-harm, and suicidal tendencies

Dermatologic

- Intertrigo, an inflammatory rash caused by skin-to-skin friction in warm, moist areas of the body

- Furunculosis (boils) or small abscesses involving hair follicles

- Hidradenitis suppurative, or inflammatory nodules or deep fluctuant cysts in the skin of the axillae and groin

- Acanthosis nigricans, or areas of dark velvety discoloration in body folds and creases, particularly the armpits, groin, and neck, associated with insulin resistance

- Striae distensae (stretch marks) caused by mechanical factors, possibly acting in concert with hormonal factors such as high levels of adrenocorticosteroids

(Skelton & Klish, 2024a; Ciezju et al., 2024; Balasundaram & Krishna, 2023)

COGNITIVE EFFECTS IN CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

Overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence are risk factors not only for general health but also for proper brain development and cognitive functions. Research has found a link between childhood obesity and alterations in brain structure, especially in the prefrontal cortex, affecting decision-making, response inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility (Vandoni et al., 2024).

Metabolic alterations induce a peripheral systemic inflammatory process that can affect the blood–brain barrier and the functioning of brain regions linked to learning and memory processes. Obesity affects the functioning of the hippocampus and produces a decrease in the prefrontal cortex gray matter, thereby modifying cognitive abilities, especially executive functions (Marti-Nicolovius, 2022).

MOTOR EFFECTS IN CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

Body composition in children and adolescents is related to the normal development of performance and gross motor coordination, and obesity can affect these. Strength, bilateral and upper limb coordination, running speed, balance, and agility are just some examples of motor activities that develop in early childhood.

Increased fat mass accumulation has been associated with a higher probability of developing a coordination deficit. Obesity results in poor performance in fine-motor precision and in manual dexterity, which can be due to difficulties with the integration and processing of sensory information.

Children with obesity show worse performance in locomotor skills due to biomechanical limitations, including:

- An increase in compressive and shear forces on the capital femoral growth plate that can alter the femoral angle

- A decrease in hip and knee flexion, resulting in stiffness while walking

Increased fat mass accumulation has been associated with a higher probability of developing coordination deficits. Children with obesity often have difficulties with coordination, including:

- Clumsiness

- Problems with gross motor coordination (jumping, hopping, balancing on one foot)

- Problems with visual or fine-motor coordination (e.g., writing, tying shoelaces)

(Vandoni et al., 2024)

PSYCHOLOGICAL/PSYCHOSOCIAL EFFECTS IN CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

Psychological effects refer to an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors; psychosocial effects refer to the interactions and relationships between an individual, family, peers, and community.

Children and adolescents with obesity experience increased risk of social isolation and poorer peer relationships, discrimination, harassment, and self-esteem. Evidence suggests that obesity is also linked to lower social and physical indicators of quality of life, as well as deteriorated dimension of parent- and school-related psychological well-being.

Research has shown that psychopathology is more frequent in children with obesity when compared to adolescents without obesity. Mental disorders such as anxiety, eating disorders, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often accompany obesity.

Those with obesity are more likely to report suicidal thoughts and attempts and are at greater risk for receiving a psychiatric diagnosis. Being male or with extreme obesity are most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity (Galler et al., 2024).

Children with obesity who have comorbid health problems such as diabetes, asthma, or sleep apnea miss school more frequently, negatively affecting their school performance.

Research has shown that individuals with obesity are more likely to not complete their education, due to adverse experiences (weight bias) within the school setting, which refers to marginalization by peers and teachers. More particularly, these experiences seem to be more frequent for girls compared to boys.

Among adolescents and young adults who were tracked after seven years, females who are overweight were found to have completed less schooling, were less likely to have married, and had higher rates of household poverty compared with their peers who are not overweight. For males who are overweight, the only adverse outcome was decreased likelihood of being married (Kokka et al., 2023; Schwarz, 2023).

Effects of Weight Bias and Stigma