Child Abuse Recognition and Reporting in Pennsylvania - Act 31 (3 Hours)

Mandated Reporter Training

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

PENNSYLVANIA ACT 31 Mandated Training on Child Abuse Recognition and Reporting Requirement. 3-contact-hour training course for PA child abuse clearance for INITIAL LICENSE APPLICATION for all mandated reporters. Pass the child abuse test and get an instant PA child abuse certificate. Approved by the PA Department of Human Services, with daily electronic reporting to the Pennsylvania Department of State (DOS). This 3 hour course partially satisfies the training requirements for PA Act 126 compliance. Any school employee who completes the course (Recognizing and Reporting of Child Abuse) will get their Act 48 credits, 3 hours, once they submit/show their certificate to their employer (the school), regardless of whether or not they go on to complete the second part of their Act 126 training (the Educator Discipline).

Course Price: $32.00

Contact Hours: 3

Course updated on

February 4, 2025

"Very clear and understandable presentation of valuable information." - Kay, RN in Pennsylvania

"This course was very detailed and helped me gain a better understanding of the signs to look for when considering possible cases of child abuse." - Stacey, nursing student in Pennsylvania

"The case studies were helpful in understanding the content." - Kimberly, PT in Pennsylvania

"Great way to present and make important processes available to nurses and all mandatory reporters." - Barbara, RN in Pennsylvania

Child Abuse Recognition and Reporting in Pennsylvania - Act 31 (3 Hours)

Mandated Reporter Training

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this course, you will be better prepared to recognize and report child abuse, child maltreatment, and child neglect. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- State the goal of the child welfare system in Pennsylvania.

- Differentiate between Child Protective Services and General Protective Services responses to reports of possible abuse or neglect.

- Describe the key components of child abuse and the categories of child abuse as defined by Pennsylvania law.

- Recognize indicators of child abuse and trafficking.

- Summarize the basis and responsibilities for reporting suspected child abuse.

- Describe the process to report child abuse.

- Identify the protections for reporters who act in good faith and penalties for failure to report.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHILD WELFARE IN PENNSYLVANIA

The Pennsylvania Child Protective Services Law (CPSL) was established in 1975. The goal of the child welfare system in Pennsylvania is to provide for the safety and well-being of children and to protect them from abuse and neglect so that they can grow up and thrive in safe, loving environments. The Commonwealth’s child welfare system exists to protect children and support families. The PA CPSL does not restrict the generally recognized existing rights of parents to use reasonable supervision and control when raising their children.

Recent amendments to the PA CPSL relevant to child abuse recognition and reporting include:

- Act 115 of 2016 (relating to human trafficking)

- Act 54 of 2018 (relating to notification of substance-affected infants by healthcare providers & plan of safe care)

- Act 88 of 2019 (relating to penalties for failure to report or refer)

The state’s Department of Human Services (DHS) oversees the child welfare system and provides technical assistance through the Office of Children, Youth, and Families (OCYF). Pennsylvania’s child welfare system is supervised by the state and administered by County children-and-youth agencies (CCYAs) have two main functions: Child Protective Services (CPS) and General Protective Services (GPS).

ChildLine is a free hotline that allows people to report suspected child abuse or neglect. Anyone can call ChildLine to report suspected abuse or general child wellbeing concerns. When a call is received by ChildLine, trained child welfare professionals can assess the concern and make a referral to the best agency to handle the concern, investigate, or provide additional support to the child and/or their family. ChildLine is staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Call 1-800-932-0313 to report suspected abuse or neglect (Commonwealth of PA, 2024b).

Bifurcated System / Two-Track Services

ChildLine professionals determine if the circumstance is to be categorized and investigated as a CPS case or categorized and assessed as a GPS case. When referrals contain allegations of incidents that meet the definition of child abuse, the case is assigned to and investigated by Child Protective Service workers. All other referrals that do not allege suspected child abuse but still present concerns for a child’s safety or well-being are assessed by General Protective Service workers.

- Child protective services are implemented when there is reasonable cause to suspect child abuse. Emergency medical services and out-of-home placement are provided when necessary for high-risk situations. CPS is contacted when at least one type of child abuse is suspected: physical, mental, sexual, or neglect.

- General protective services are offered when there is concern about something in the home or for nonabuse cases that require support and services to prevent harm to the child. Examples include poor hygiene, inappropriate discipline, inadequate supervision, truancy, and inadequate shelter or clothing. There is no investigation component to this response. GPS protects the welfare and safety of children by aiding parents in fulfilling their parental duties and by helping them to recognize and correct potentially harmful conditions.

| Child Protective Services | General Protective Services |

|---|---|

| (PA DHS, 2024b) | |

|

|

|

|

|

Examples of CPS cases:

|

Examples of GPS cases:

|

REASONABLE CAUSE TO SUSPECT

“Reasonable cause to suspect” is a determination made based on training/experience and all known circumstances—to include “who,” “what,” “when,” and “how” observations. These may include indicators of abuse, “red flags,” behavior/demeanor of the child, and behavior/demeanor of the adult, etc. Observation may also be based on familiarity with the individuals (e.g., family situation and relevant history or similar prior incidents, etc.).

Some indicators may be more apparent than others, depending on the type of abuse and/or depending on the child’s health, developmental level, and well-being. For example, some indicators may be visible on the child's body, while other indicators may be present in the child's behaviors.

(See also “Recognizing Abuse” later in this course.)

CASE

Esmerelda, a school teacher, stops by her friend Janie’s house for coffee. While she is there, Janie’s son, Caden, who is a student in Esmerelda’s class, runs into the kitchen and for no apparent reason aggressively shoves his 2-year-old sister, who falls to the floor. Caden, age 7, has been diagnosed with a spectrum disorder. While the sister is not injured, Janie yells at Caden, picks him up, and throws him across the kitchen, where he slides into a cabinet, hitting the back of his head.

Concerned for his well-being, Esmerelda examines Caden and finds that he is okay. Even so, Esmerelda recognizes the importance of taking action for the safety of her student. She empathizes with Janie and expresses her concern for the family. She acknowledges how frightening and stressful it must be for Janie to have a child with a serious condition. She then shifts to a professional role, asking Janie if she can refer Caden to a program for children with learning differences that is provided by the school district. Janie tearfully agrees, and Esmerelda makes a call to the school district to gather information about the program.

Esmerelda, who is a mandated reporter, also remembers that the law in Pennsylvania states that she is required to report to ChildLine because she is a teacher who has responsibility for her students. She also has reasonable cause to suspect that Caden may be a victim of child abuse due to the severity of the incident that she observed. Esmerelda lets Janie know that she must make an immediate report to ChildLine. When calling in her report by phone, Esmerelda describes the incident, including Janie’s desire to help her child and her voluntary interest in a referral to services that can help her. Esmerelda follows up later that day with a written report on the CY-47 form and submits it to the CWIS.

Esmerelda makes a point to call Janie the next day and frequently thereafter. Two months later, Janie tells Esmerelda that a social worker helped her find a program in which she is learning appropriate new ways of dealing with the challenge of Caden’s spectrum disorder.

WHAT IS CHILD ABUSE?

It is imperative that healthcare professionals and other mandated reporters know how the various categories of child abuse are defined.

Categories of Child Abuse

Child abuse may take many forms. Pennsylvania’s Child Protective Services Law (CPSL) categorizes abuse into the following types:

- Physical

- Mental

- Sexual

- Neglect

- Severe forms of trafficking in persons (human trafficking)

Mandated reporters must learn to recognize the indicators for the various forms of child abuse. (See also “Recognizing Abuse” later in this course.)

KEY COMPONENTS OF CHILD ABUSE

The Pennsylvania CPSL recognizes three key components of child abuse:

- Child: An individual under 18 years of age

- Recent act or failure to act

- Recent: Committed within two years of the date of the report to DHS or county agency

- Act: Something that is done to harm or cause potential harm to a child

- Failure to act: Something that is not done to prevent harm or potential harm to a child

- Intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly

- Intentionally: Done with the direct purpose of causing the type of harm that resulted

- Knowingly: Awareness that harm is practically certain to result

- Recklessly: Conscious disregard of substantial and unjustifiable risk

(23 Pa.C.S. § 6303; 18 Pa.C.S. § 302)

DEFINITIONS OF TERMINOLOGY RELATED TO CHILD ABUSE

- Direct contact with children

- Care, supervision, guidance, or control of children or routine interaction with children

- Person responsible for the child’s welfare

- A person who provides permanent or temporary care; supervision; mental health diagnosis; or treatment, training, or control of a child in lieu of parental care, supervision, or control

- Student

- An individual enrolled in a public or private school, intermediate unit, or area vocational-technical school who is under 18 years of age

- School employee

- An individual employed by a school or who provides a program, activity, or service sponsored by a school (does not apply to administrative or other support personnel unless the administrative or other support personnel have direct contact with the children)

- Bodily injury

- Causing what a reasonable person believes to be substantial pain or any impairment in physical condition in which the child’s ability to function is reduced temporarily or permanently in any way (replaces term serious physical injury, which was deleted by amendment from the Pennsylvania statute)

- Serious mental injury

-

A psychological condition, as diagnosed by a physician or licensed psychologist, including the refusal of appropriate treatment, that:

- Renders a child chronically and severely anxious, agitated, depressed, socially withdrawn, psychotic, or in reasonable fear that the child’s life or safety is threatened; or

- Seriously interferes with a child’s ability to accomplish age-appropriate developmental and social tasks

- Serious physical neglect

-

Any of the following when committed by a perpetrator that endangers a child’s life or health, threatens a child’s well-being, causes bodily injury, or impairs a child’s health, development, or functioning:

- A repeated, prolonged, or egregious failure to supervise a child in a manner that is appropriate considering the child’s developmental age and abilities

- The failure to provide a child with adequate essentials of life, including food, shelter, or medical care

- Severe forms of trafficking in persons (human trafficking)

- Sex trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not obtained 18 years of age (i.e., sex trafficking does not require there be force, fraud, or coercion if the victim is under 18). Examples include prostitution, pornography, exotic dancing, etc.

- Labor trafficking in which labor is obtained by use of threat or serious harm, physical restraint, or abuse of legal process, including the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage (paying off debt through work), debt bondage (debt slavery, bonded labor, or services for a debt or other obligation), or slavery (a condition compared to that of a slave in respect to exhausting labor or restricted freedom). Examples include being forced to work for little or no pay (frequently in factories or on farms) or domestic servitude (providing child care, cooking, cleaning, yardwork, gardening from 10 to 16 hours per day).

(23 Pa. C.S. § 6303; U.S. Public Law 106-386 § 103.)

Definition of Child Abuse

CPSL, 23 Pa. C.S. § 6303, defines “child abuse” as intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly doing any of the following:

- Causing bodily injury to a child through any recent act or failure to act

- Fabricating, feigning, or intentionally exaggerating or inducing a medical symptom or disease which results in a potentially harmful medical evaluation or treatment to the child through any recent act

- Causing or substantially contributing to serious mental injury to a child through any act or failure to act or a series of such acts or failures to act

- Causing sexual abuse or exploitation of a child through any act or failure to act [see also “Definition of Sexual Abuse or Exploitation” below]

- Creating a reasonable likelihood of bodily injury to a child through any recent act or failure to act

- Creating a likelihood of sexual abuse or exploitation of a child through any recent act or failure to act

- Causing serious physical neglect of a child

- Engaging in any of the following recent acts:

- Kicking, biting, throwing, burning, stabbing, or cutting a child in a manner that endangers the child

- Unreasonably restraining or confining a child, based on consideration of the method, location, or the duration of the restraint or confinement

- Forcefully shaking a child under one year of age

- Forcefully slapping or otherwise striking a child under one year of age

- Interfering with the breathing of a child

- Causing a child to be present [when the] operation of a methamphetamine laboratory is occurring

- Leaving a child unsupervised with an individual, other than the child’s parent, who the actor knows or reasonably should have known […] is required to register as a sexual offender […] has been determined to be a sexually violent predator […] has been determined to be a sexually violent delinquent child

- Causing the death of the child through any act or failure to act

- Engaging a child in a severe form of trafficking in persons or sex trafficking, as those terms are defined under section 103 of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000

Definition of Sexual Abuse or Exploitation

CPSL, 23 Pa. C.S. § 6303, further defines “sexual abuse or exploitation” as any of the following:

- The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, enticement, or coercion of a child to engage in or assist another individual to engage in sexually explicit conduct, which includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- Looking at the sexual or other intimate parts of a child or another individual for the purpose of arousing or gratifying sexual desire in any individual

- Participating in sexually explicit conversation either in person, by telephone, by computer, or by a computer-aided device for the purpose of sexual stimulation or gratification of any individual

- Actual or simulated sexual activity or nudity for the purpose of sexual stimulation or gratification of any individual

- Actual or simulated sexual activity for the purpose of producing visual depiction, including photographing, videotaping, computer depicting, or filming (This paragraph does not include consensual activities between a child who is 14 years of age or older and another person who is 14 years of age or older and whose age is within four years of the child’s age.)

- Any of the following offenses committed against a child:

- Rape (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3121)

- Statutory sexual assault (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3122.1)

- Involuntary deviate sexual intercourse (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3123)

- Sexual assault (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3124.1)

- Institutional sexual assault (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3124.2)

- Aggravated indecent assault (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3125)

- Indecent assault (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3126)

- Indecent exposure (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3127)

- Incest (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 4302)

- Prostitution (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 5902)

- Sexual abuse (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 6312)

- Unlawful contact with a minor (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 6318)

- Sexual exploitation (as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 6320)

Definition of Perpetrator

As described in CPSL, 23 Pa. C.S. § 6303 and § 6304:

- A “perpetrator” is a person who has committed child abuse and who is:

- A parent of the child

- A spouse or former spouse of the child’s parent

- A paramour or former paramour of the child’s parent

- A person 14 years of age or older and responsible for the child’s welfare or having direct contact with children as an employee of a child-care service, a school, or through a program, activity, or service

- An individual 14 years of age or older who resides in the same home as the child

- An individual 18 years of age or older who does not reside in the same home as the child but is related within the third degree of consanguinity or affinity by birth or adoption to the child

- An individual 18 years of age or older who engages a child in severe forms of trafficking in persons or sex trafficking, as those terms are defined under section 103 of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000

- In cases involving “failure to act,” perpetrators include only the following:

- A parent of the child

- A spouse or former spouse of the child’s parent

- A paramour or former paramour of the child’s parent

- A person 18 years of age or older and responsible for the child’s welfare

- A person 18 years of age or older who resides in the same home as the child

Current Pennsylvania law expanded the previous definition of perpetrators to include relatives who do not live with the child as well as those engaging a child in trafficking. It also now includes those responsible for the child’s welfare, defined as:

A person who provides permanent or temporary care, supervision, mental health diagnosis or treatment, training or control of a child in lieu of parental care, supervision, and control. The term includes any such person who has direct or regular contact with a child through any program, activity, or service sponsored by a school, for-profit organization, or religious or other not-for-profit organization.

Exclusions

There are two types of exclusions described in the law. “Exclusions to reporting” are instances in which a child may suffer harm but for which a mandated reporter is not required to make a report. “Exclusions from child abuse” (sometimes called “exclusions to substantiating a report”) are instances in which harm to a child must be reported but for which the investigating team may determine that no child abuse has occurred.

EXCLUSIONS TO REPORTING

There are only two situations in which persons who fall under the mandated reporter law are excluded from the requirement to report suspected child abuse:

- Confidential communications made by a communicant to a member of the clergy who is acting in the role of confessor or spiritual counselor, per 42 Pa. C.S. § 5943

- Confidential communications made to an attorney within the scope of confidentiality as per 42 Pa. C.S. §§ 5916 and 5928. This is related to situations in criminal or civil proceedings in which neither the attorney nor client are required or permitted to disclose the communications unless the client waives the privilege.

(CWIG, 2019)

It is important to understand that privileged communication between a mandated reporter and a client does not apply to situations of suspected child abuse. This includes counselors, school psychologists, and social workers. These persons have an absolute duty to report suspected abuse without exception (23 Pa. C.S. § 6311.1).

EXCLUSIONS FROM CHILD ABUSE

Sections 6303 and 6304 of the CPSL explains situations that are considered “exclusions to child abuse.” Most of these situations must still be reported. At times, however, the CPS investigation may reveal other factors and the report found to be unsubstantiated. That is, the child will not be deemed to be abused by investigators.

Exclusions from child abuse include conduct that causes injury or harm to a child or creates a risk of injury or harm to a child in which there is no evidence that the person acted intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly (i.e., no culpability) when causing the injury or harm to the child or creating a risk of injury or harm to the child.

Exclusions from child abuse also include:

- Injuries that result solely from environmental factors, such as inadequate housing, furnishings, income, clothing, or medical care that are beyond the control of the parent or person with whom the child lives.

- The child has not been provided needed medical or surgical cause because of sincerely held religious beliefs of the child’s parents or relative within the third degree of consanguinity and with whom the child resides. In such cases:

- The county agency shall closely monitor the child and the child's family and shall seek court-ordered medical intervention when the lack of medical or surgical care threatens the child’s life or long-term health.

- All correspondence with a subject of the report and the records of the department and the county agency shall not reference child abuse and shall acknowledge the religious basis for the child’s condition.

- The family shall be referred for general protective services, if appropriate.

- This exclusion shall not apply if the failure to provide needed medical or surgical care causes the death of the child.

- This exclusion shall not apply to any childcare service as defined in this chapter, excluding an adoptive parent.

- The use of reasonable force on or against a child by the child’s own parent or person responsible for the child’s welfare (see also “rights of parents” below), if any of the following conditions apply:

- The use of reasonable force constitutes incidental, minor, or reasonable physical contact with the child or other actions that are designed to maintain order and control

- The use of reasonable force is necessary for the child’s safety and in order to:

- To quell a disturbance or remove the child from the scene of a disturbance that threatens physical injury to persons or damage to property

- To prevent the child from self-inflicted physical harm

- For self-defense or the defense of another individual

- To obtain possession of weapons or other dangerous objects or controlled substances or paraphernalia that are on the child or within the control of the child

- Parents’ use of reasonable force on or against their children (i.e., the generally recognized existing “rights of parents”) for the purposes of supervision, control, and discipline of their children. (Such reasonable force shall not constitute child abuse.)

- Participation in events that involve physical contact, such as a practice or competition in an interscholastic sport, physical education, recreational activity, or extracurricular activity (such contact is not subject to child abuse reporting requirements)

- Harm or injury to a child that results from the act of another child (child-on-child contact), unless the child who caused the harm or injury is a perpetrator, in which the following shall apply:

- Acts constituting any of the following crimes against a child shall be subject to the reporting requirements of the PA CPSL:

- Rape as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3121 (relating to rape);

- Involuntary deviate sexual intercourse as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3123 (relating to involuntary deviate sexual intercourse);

- Sexual assault as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3124.1 (relating to sexual assault);

- Aggravated indecent assault as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3125 (relating to aggravated indecent assault);

- Indecent assault as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3126 (relating to indecent assault); and

- Indecent exposure as defined in 18 Pa.C.S. § 3127 (relating to indecent exposure).

- No child shall be deemed to be a perpetrator of child abuse based solely on physical or mental injuries caused to another child in the course of a dispute, fight, or scuffle entered into by mutual consent.

- A law enforcement official who receives a report of suspected child abuse is not required to make a report to DHS if the person allegedly responsible for the child abuse is a non-perpetrator child.

- Acts constituting any of the following crimes against a child shall be subject to the reporting requirements of the PA CPSL:

- Defensive force that is reasonable force for self-defense or the defense of another individual that is used for self-protection or for the protection of another person

(23 Pa.C.S. § 6304 and § 6304)

However, nothing in the PA CPSL requires a person who has a reasonable cause to suspect a child is a victim of child abuse to consider these exclusions from child abuse to make a report of suspected child abuse.

RISK FACTORS

Health professionals must remain alert for risk factors that may increase the likelihood of child abuse and maltreatment. Risk factors may be either characteristics of a caregiver or of a child and may go undetected.

Risk Factors for Perpetrating Child Abuse

A caregiver may have certain characteristics that increase the likelihood that they may become a perpetrator of child abuse or neglect. When health professionals observe indicators of possible abuse, they should consider whether the presence of risk factors in a caregiver may signal a need to examine the situation more carefully.

Individual risk factors include:

- Caregivers with drug or alcohol issues

- Caregivers with mental health issues, including depression

- Caregivers who don't understand children's needs or development

- Caregivers who were abused or neglected as children

- Caregivers who are young or single parents or parents with many children

- Caregivers with low education or income

- Caregivers experiencing high levels of parenting stress or economic stress

- Caregivers who use spanking and other forms of corporal punishment for discipline

- Caregivers in the home who are not a biological parent

- Caregivers with attitudes accepting of or justifying violence or aggression

Relationship/family risk factors include:

- Families that have household members in jail or prison

- Families that are isolated from and not connected to other people (extended family, friends, neighbors)

- Families experiencing other types of violence, including relationship violence

- Families with high conflict and negative communication styles

Community risk factors include:

- Communities with high rates of violence and crime

- Communities with high rates of poverty and limited educational and economic opportunities

- Communities with high unemployment rates

- Communities with easy access to drugs and alcohol

- Communities where neighbors don't know or look out for each other

- Communities where there is low community involvement among residents

- Communities with few community activities for young people

- Communities with unstable housing and where residents move frequently

- Communities where families frequently experience food insecurity

(CDC, 2024a)

Nationally, the most common risk factors reported with child maltreatment are substance abuse and domestic violence (U.S. DHHS, 2024).

Child Risk Factors

While children are not responsible for being abused, certain factors increase their risk for abuse or neglect:

- Children younger than 4 years of age

- Children with special needs that may increase caregiver burden (disabilities, mental health issues, and chronic physical illnesses)

(CDC, 2024a)

Youth at greater risk for human trafficking include those who have experienced:

- A history of abuse and neglect

- Social disconnection

- Social stigma and exclusions

(NHTTTAC, n.d.)

(See also “Recognizing Trafficking” later in this course.)

PARENTAL SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND CHILD ABUSE

Parental substance abuse greatly increases the incidence of child abuse and neglect. A review of research on parental substance abuse and its impact on children showed that:

- 1 in 5 children in the United States live in homes with parental substance abuse.

- Parents who are chemically dependent are unable to effectively parent their children.

- The health and development of children is negatively impacted by parental substance abuse.

- Children who grow up in homes with prevalent substance abuse are more likely to misuse drugs and alcohol since such norms are established at a young age.

(Thatcher, 2020)

RECOGNIZING ABUSE

There are many possible indicators of child maltreatment or abuse, and these indicators should be viewed together, not in isolation. Similarly, each indicator must be considered in relation to the child’s current age and circumstances and in the context of their physical condition or behavior. These indicators are not all inclusive, and some children may not demonstrate signs or symptoms of abuse or neglect.

Another important aspect to assessing for possible abuse is obtaining an explanation for the presenting concern and whether that explanation is consistent with the observed physical and behavioral indicators. Abuse or maltreatment should never be assumed.

The mandated reporter is encouraged to consider any prior experiences with the child and possible differences between past and present observations.

Any assessment must be objective and free from implicit or explicit bias.

Recognizing Bodily Injury

The category of physical abuse involves any recent act or failure to act by a perpetrator that causes bodily injury to a child. Bodily injury is defined in the CPSL as “impairment of physical condition or substantial pain” (23 Pa.C.S. § 6303).

PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF BODILY INJURY

Mandatory and permissive reporters must be alert for physical injuries that are unexplained or inconsistent with the parent or other caretaker’s explanation or the developmental state of the child. However, it is important to remember that indicators of maltreatment or abuse may not always be of a physical nature or visible to view.

Bruising

Bruising is the most common indicator of physical child abuse, and attention to bruises can be an important factor in identifying children who are at risk of physical abuse. It is important to know both normal and suspicious bruising patterns when assessing children’s injuries. Normal bruising usually occurs in the front of the body over bony areas such as the forehead, knees, shins, and elbows.

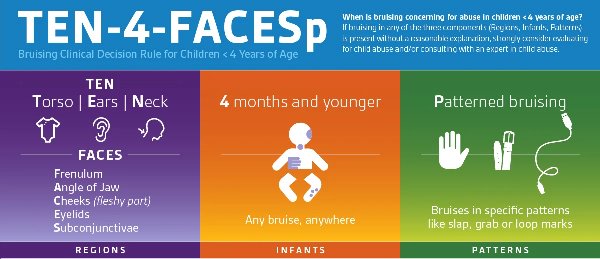

The TEN-4-FACESp validated clinical screening tool, developed by Dr. Mary Clyde Pierce, can be used to evaluate bruises in children under 4 years of age. The tool guides the clinician to assess bruising associated with three components (regions, infants, patterns) if there is no reasonable explanation for a bruise (Pierce et al., 2021). Children who are under 4 years should not have any bruises in the areas indicated in the chart below, and infants under 4 months should have no bruises anywhere. The size of the bruise is not as important as the location.

(Source: © Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.)

This pattern signals the blow of a hand to the face of a child. (Source: Research Foundation of SUNY, 2011.)

Regular patterns reveal that a looped cord was used to inflict injury on this child. (Source: Research Foundation of SUNY, 2011.)

Lacerations or Abrasions

Typical indications of unexplained lacerations and abrasions that are suspicious include:

- On the face, lips, or mouth

- To external genitalia

Burns

Unexplained burns include:

- Cigar or cigarette burns, especially on soles, palms, back, or buttocks

- Immersion burns by scalding water (sock-like, glove-like, doughnut-shaped on buttocks or genitalia; “dunking syndrome”)

- Patterned like an electric burner, iron, curling iron, or other household appliance

- Rope burns on arms, legs, neck, or torso

A steam iron was used to inflict injury on this child. (Source: Research Foundation of SUNY, 2011.)

Fractures

Unexplained fractures may include:

- Fractures to the skull, nose, or facial structure

- Multiple or spiral fractures

- Fractures in various stages of healing

(SD DSS, 2020)

Head Injuries

Typical indications of unexplained head injuries include:

- Absence of hair or hemorrhaging beneath the scalp due to vigorous hair pulling

- Subdural hematoma (a hemorrhage beneath the outer covering of the brain, due to severe hitting or shaking)

- Retinal hemorrhage or detachment, due to shaking

- Whiplash or pediatric abusive head trauma (see box below)

- Eye injury

- Jaw and nasal fractures

- Tooth or frenulum (of the tongue or lips) injury

PEDIATRIC ABUSIVE HEAD TRAUMA

Pediatric abusive head trauma (AHT) is an inflicted head injury in children that can be caused by various mechanisms, including rotational and contact forces to the head as well as shaking. Secondary brain injury may occur as a result of hypoxia, ischemia, or inflammation, and almost all children who experience AHT develop serious long-term health problems. Impairments that result from AHT may include encephalopathy, intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, cortical blindness, seizure disorders, behavior problems, and learning disabilities. Endocrine dysfunction is commonly seen in survivors of AHT and may be observed years after the event.

AHT is the chief cause of child abuse deaths in children under the age of 5 in the United States, with approximately one third of all child abuse deaths attributed to AHT. Furthermore, up to 1 in 4 children who suffer AHT will die from resulting injury (CDC, 2024b).

The clinical presentation of infants or children with AHT can vary. Findings may be subtle and include:

- Bruising (see “TEN-4-FACESp” above)

- Oral injuries such as frenulum tears

- Retinal hemorrhages that are numerous, found in all layers of the retina, extend to the periphery of the retina, or retinoschisis (blood in the macula)

- Skull fractures

- Cerebral edema

- Subdural hemorrhages

- Spinal subdural hemorrhages

AHT should be considered when infants or young children present with:

- Fussiness or altered mental status

- Vomiting

- Apnea

Short falls (less than five feet) are often the explanation given to the provider for the injury; however, serious injury or death is unlikely to result from a short fall. In addition to conducting a thorough examination with imaging when AHT is suspected, clinicians should report to Child Protective Services and educate parents about the dangers of AHT from shaking or striking a child or impacting the child’s head against a surface. It is also important to educate parents about alternatives to soothe a crying baby (Narang et al., 2020).

Recognizing Serious Mental Injury

Serious mental injury is defined by the CPSL as a psychological condition diagnosed by a physician or licensed psychologist that:

- Renders the child chronically and severely anxious, depressed, socially withdrawn, psychotic, or in reasonable fear that their safety is threatened

- Seriously interferes with the child’s ability to accomplish age-appropriate developmental and social tasks

(23 Pa. C.S. § 6303)

Physical indicators in a child of serious mental injury include:

- Frequent nonspecific somatic complaints (stomachache, nausea, headache)

- Enuresis

- Self-harm

- Speech disorders

Behavioral indicators in a child of mental injury include:

- Statements about feeling inadequate

- Fearfulness of trying new things

- Passive behavior, overly compliant

- Poor social relationships with peers

- Exceedingly dependent on adults

- Habits such as thumb-sucking, picking, rocking

- Eating disorders

(Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 2024)

A parent or guardian exhibiting the following indicators may be a perpetrator of serious mental injury against a child:

- Making unreasonable demands on the child

- Not considering child’s developmental stage

- Using the child as an issue in marital conflict

- Using the child to satisfy caretaker’s needs

- Objectifying the child (e.g., involving the child in beauty pageants)

- Engaging in acts of domestic violence in front of the child

(American SPCC, 2021)

Recognizing Sexual Abuse

(See also “Definition of Sexual Abuse or Exploitation” earlier in this course.)

Child sexual abuse involves the coercion of a dependent, developmentally immature person to commit a sexual act with someone older. For example, an adult may sexually abuse a child or adolescent or an older child or adolescent may abuse a younger child. A perpetrator does not have to be an adult in order to sexually abuse a child (RAINN, 2021).

The fact that sexual abuse may be carried out by a family member or friend further increases the child’s reluctance to disclose the abuse, as does shame and guilt plus the fear of not being believed. The child may fear being hurt or even killed for telling the truth and may keep the abuse secret rather than risk the consequences of disclosure. Very young children may not have sufficient language skills or vocabulary to describe what happened (Clermont County CPS, 2021; RAINN, 2021).

Child sexual abuse is found in every race, culture, and class throughout society. Girls are sexually abused more often than boys; however, this may be due to boys’—and later, men’s—tendency not to report their victimization.

Most perpetrators of child sexual abuse are people who are known to the victim. As many as 93% of children who are sexually abused under the age of 18 know the abuser. There is no particular profile of a child molester or of the typical victim. Even someone highly respected in the community—the parish priest, a teacher, or coach—may be guilty of child sexual abuse. Anyone, including parents, can be a perpetrator, and most are male.

Negative effects of sexual abuse vary from person to person and range from mild to severe in both the short and long term. Victims may exhibit anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and depression. They may develop eating disorders, self-injury behaviors, substance abuse, or suicide. The effects of childhood sexual abuse often persist into adulthood (Clermont County CPS, 2021; RAINN, 2021).

PHYSICAL INDICATORS OF SEXUAL ABUSE

Physical evidence of sexual abuse may not be present or may be overlooked. Victims of child sexual abuse are seldom injured due to the nature of the acts. Most perpetrators of child sexual abuse go to great lengths to “groom” the children by rewarding them with gifts and attention and try to avoid causing them pain in order to ensure that the relationship will continue.

If physical indicators occur, they may include:

- Symptoms of sexually transmitted diseases, including oral infections, especially in preteens

- Difficulty in walking or sitting

- Torn, stained, or bloody underwear

- Pain, itching, bruising, or bleeding in the genital or anal area

- Bruises to the hard or soft palate

- Pregnancy, especially in early adolescence

- Painful discharge of urine or repeated urinary infections

- Foreign bodies in the vagina or rectum

- Painful bowel movements

(Clermont County CPS, 2021; RAINN, 2021; NYS OCFS, n.d.)

BEHAVIORAL INDICATORS OF SEXUAL ABUSE

Children’s behavioral indicators of child sexual abuse include:

- Unwillingness to change clothes for or participate in physical education activities

- Withdrawal, fantasy, or regressive behavior, such as returning to bedwetting or thumb-sucking

- Inappropriate, bizarre, suggestive, or promiscuous sexual behavior

- Inappropriate sexual knowledge for age

- Verbal disclosure of sexual assault

- Involvement in commercial sexual exploitation

- Forcing sexual acts on other children

- Extreme fear of closeness or physical examination

- Suicide attempts or other self-injurious behaviors

- Layered or inappropriate clothing

- Hiding clothing

- Lack of interest or involvement in activities

(Clermont County CPS, 2021; RAINN, 2021; NYS OCFS, n.d.)

Sexually abusive parents/guardians or other persons legally responsible may exhibit the following behaviors:

- Overly protective

- Jealous of child

- Does not allow the child to participate in social activities

- Accuses the child of promiscuity

- Has marital problems

- Authoritarian

- Favoring one child in the family

- Need for control

- History of sexual abuse

(Clermont County CPS, 2021)

Recognizing Trafficking

The media often portrays trafficking victims as women who are in chains or have a sign written on their hands that says, “Help Me.” However, this is not what most trafficking victims look like. When victims of human trafficking present in healthcare settings, it is uncommon for them to self-disclose that they are victims. They have significant trust issues, and even when asked directly, they are not likely to disclose that they are victims. The exploiter may also accompany victims, and as with victims of domestic violence, that presence will discourage victims from making any disclosures to a clinician.

It is important for healthcare providers to ask about exploitation because up to 88% of adolescent victims of trafficking reported an encounter with a healthcare provider during the time that they were being exploited (Polaris, 2024).

TYPES OF TRAFFICKING

The crime of sex trafficking of children is a type of child abuse increasingly encountered in the healthcare setting. It is defined in the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (18 USC § 1591) as “to recruit, entice, harbor, transport, provide, obtain, or maintain by any means a person, or to benefit financially from such action, knowing or in reckless disregard that the person has not attained the age of 18 years and will be caused to engage in a commercial sex act.”

In 2023, an estimated 1 in 6 of the 28,800 U.S. children who were reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC) as missing were likely trafficked. It is likely that an estimated 19% of the children who ran away from foster care also became involved in sex trafficking in the same year. And NCMEC received 18,400 reports of child sex trafficking in 2023 (NCMEC, 2024).

According to U.S. federal law (22 USC § 7102), labor trafficking is the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purposes of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery. As with sex trafficking, force, fraud, or coercion do not need to exist if the labor trafficking victim is under the age of 18.

Child labor trafficking may include agricultural, domestic service, or factory work where workers provide involuntary labor. Labor trafficking can also occur in beauty services, restaurants, small businesses, or informal settings. Some common situations include peddling and traveling sales crews where young people are moved from town to town selling cheap products such as jewelry or magazines for little or no pay. Other situations include drug dealing in which children are forced to sell drugs.

Sometimes labor trafficking may occur when a child is staying with a custodial family member or nonfamily member and is forced to work. Children are controlled through fear and abuse by their traffickers. It is possible that a child is a victim of labor and sex trafficking simultaneously (NCSSLE, 2021).

SIGNS OF TRAFFICKING

Pennsylvania has developed and implemented statewide a tool to screen children for trafficking. The Child Victims of Human Trafficking (CVHT) screening tool has been in use since 2019. It allows child welfare professionals to screen and assess children by identifying the following indicators that a child may be involved with trafficking:

- Current incident or history of previous sex or labor trafficking or acknowledgement of being trafficked

- Being recovered from a runaway episode in a hotel or known area of prostitution

- Report of sex or labor trafficking by parent/guardian, law enforcement, medical or service provider, teacher, child protective services, or juvenile probation officer

- History of running away or getting kicked out four or more times in addition to a history of sexual abuse

- History of running away from another county or state

- Current incident or history of inappropriate sexual behaviors

- Current incident or history of sexually transmitted diseases or pregnancies

- Child not being allowed or unable to speak for themself and being extremely fearful

- Child having no personal items or possessions (including identity documents)

- Child appearing to have material items that they cannot afford (e.g., cell phones, expensive clothing, tablets, etc.)

- Child showing signs of being groomed (i.e., hair done, nails done, new clothing, etc.)

(PA DHS, 2019)

Other indicators of possible human trafficking in the healthcare setting include:

- Delaying seeking care for an illness

- Malnourishment

- Physical injuries consistent with long-term abuse, such as bruises in various stages of healing or signs of physical or sexual abuse

- Substance use

- Poor hygiene

- Health conditions of vulnerability such as disabilities and mental health issues

- Giving scripted answers/stories

- Minimizing abuse or injuries

- Being anxious

- Not being aware of location, date, or time of day

- Hesitating when answering questions about an injury or illness

- Symptoms related to depression or PTSD

- Presence of a third party who monitors the child’s responses, answers for them, behaves in an aggressive or verbally abusive manner, insists on filling out paperwork, or demands to remain in the room with the child

- Leaving against medical advice or seeming pressured to leave quickly

- Reporting not having a fixed address

(Polaris, 2024)

CASE

Brittany, age 14, met a young man at the mall who told her she was beautiful. They exchanged phone numbers and began talking on a regular basis. He gave her gifts, and Brittany thought she was in love. Brittany was being “groomed,” one of the ways that exploiters gain trust and control over victims.

Brittany’s new “boyfriend” soon asked her to have sex with him and, not long after, with other men. Although she said she did not want to be with other men, she did it anyway because she wanted to please her boyfriend. Brittany’s mother was addicted to drugs, and she also had a history of physical, mental, and sexual abuse in the home, which made Brittany particularly vulnerable to the methods of exploiters because the cycle of abuse was familiar to her.

Soon, Brittany was sold to another exploiter, who beat her if she did not make any money and took all her money when she was paid. She was locked in a basement and slept on a mattress on the floor, with only a bucket to use as a toilet. Devoid of job skills, money, and fearing further abuse if she tried to escape to her home, Brittany felt trapped.

Brittany’s exploiter took her for frequent STI testing at various free clinics to avoid suspicion. Chandra, a nurse practitioner who volunteered at several of the clinics, began to recognize Brittany. At the insistence of her exploiter, Brittany always registered as an 18-year-old whenever she requested services, but Chandra suspected that Brittany was probably younger. Before asking Brittany her true age, Chandra made an effort to gain Brittany’s trust, and Brittany confided that she was only 14. This increased Chandra’s suspicion that Brittany was a minor victim of sex trafficking, and so she made an immediate report to ChildLine.

Recognizing Serious Physical Neglect

The category of neglect is defined in the CPSL as serious physical neglect by a perpetrator constituting prolonged or repeated lack of supervision or the failure to provide the essentials of life, including adequate medical care, which endangers a child’s life or development or impairs the child’s functioning (23 Pa. C.S. § 6303).

Physical indicators of physical neglect include:

- Consistent hunger

- Poor hygiene (skin, teeth, ears, etc.)

- Inappropriate attire for the season

- Failure to thrive (physically or emotionally)

- Positive indication of toxic exposure, especially in newborns, such as drug withdrawal symptoms, tremors, and so forth

- Delayed physical development

- Speech disorders

- Consistent lack of supervision, especially in dangerous activities or for long periods of time

- Unattended physical problems or medical or dental needs

- Chronic truancy

- Abandonment

(Clermont County CPS, 2021)

A child may demonstrate behavioral indicators of neglect such as:

- Begging or stealing food

- Extended stays at school (early arrival or late departure)

- Constant fatigue, listlessness, or falling asleep in class

- Alcohol or other substance abuse

- Delinquency, such as shoplifting

- Reports there is no caretaker at home

- Runaway behavior

- Habit disorders (sucking, nail biting, rocking, etc.)

- Conduct disorders (antisocial or destructive behaviors)

- Neurotic traits (sleep disorders, inhibition of play)

- Psychoneurotic reactions (hysteria, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, phobias, hypochondria)

- Extreme behavior (compliant or passive, aggressive or demanding)

- Overly adaptive behavior (inappropriately adult, inappropriately infantile)

- Delays in mental or emotional development

- Suicide attempt

(Clermont County CPS, 2021)

ABANDONMENT OF AN INFANT

Another form of neglect is the abandonment of an infant. Pennsylvania has established a “Safe Haven” law that allows parents to relinquish newborns up to 28 days old at any hospital, police station, or emergency medical services (EMS) agency without the fear of criminal prosecution as long as the baby has not been harmed and is not a victim of a crime. The purpose of the Safe Haven law is to decriminalize leaving unharmed infants anonymously in a safe location in order to save the lives of infants who may be unwanted by their parents.

According to Pennsylvania’s Safe Haven law:

- The baby may be given to a hospital staff member without the parent providing any further information. The baby may also be left at a hospital without giving it to anyone, and some hospitals even have a crib or bassinet available for that purpose.

- If a baby is relinquished to a police station, it must be given to a police officer.

- If a baby is relinquished at an emergency medical services agency, it must be given to an EMS responder.

Additional information is available by calling the Safe Haven Helpline (see “Resources” at the end of this course).

Any mandated reporter who learns of abandonment is obligated to fulfill mandated reporter responsibilities (see “Provisions and Responsibilities for Reporting Suspected Child Abuse” later in this course). Failure to report acceptance of newborns is considered to be a felony of the third degree.

(PA DHS, 2021)

RECOGNIZING AND RESPONDING TO VICTIMS’ DISCLOSURES

It is difficult for young children to describe abuse. They may only disclose part of what happened, or they may make an indirect disclosure such as, “My stepdad keeps me up at night.” It is important not to rush the child and to listen to their concerns so that the child feels safe and supported. If a child discloses abuse, the following actions by the healthcare professional will help the child:

- Avoid denying what the child discloses

- Provide safety and reassurance

- Listen without making assumptions

- Do not interrogate

- Limit questioning to only four queries:

- What happened?

- When did it happen?

- Where did it happen?

- Who did it? (How do you know them?)

- Do not make promises

- Document the child’s statements using exact quotes

- Remain nonjudgmental and supportive

- Understand the dynamics of abuse and neglect

- Report suspicions to the authorities

(Childhelp, 2021)

Interviewing for Sexual Assault

If a child or adolescent discloses sexual abuse to a trusted adult or there is cause for the adult to suspect sexual abuse, the adult should not question the child further. They should instead contact Child Protective Services or, if the child is in imminent danger, the police. These professionals have protocols in place to interview the child by a child interview specialist while police, prosecutors, and caseworkers observe.

Such forensic interviewers are trained to communicate in an age- and developmentally appropriate manner. Coordination of services with a child forensic interviewer is essential to minimize trauma and to ensure the use of evidence-based practices to listen more effectively to the child. Forensic interviewers rely on critical thinking, ethical standards, and professional judgment. They must participate in ongoing training and peer review. The American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children published updated practice guidelines for forensic interviewing in 2023 (APSAC Taskforce, 2023).

Management

A physically abused child is screened for emergent needs. Once stability has been established, the child undergoes a history and physical. ChildLine should be informed when there is a suspicion of abuse and the child may need to be seen in an in-patient facility so that lab work and imaging can be done.

A child who has been sexually abused is also evaluated for physical, mental, and psychosocial needs. Baseline testing is performed for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for children of all ages. Pregnancy and empiric treatment for STIs may also be given to adolescent victims. STI prophylaxis and emergency contraception may be offered if the patient presents within 120 hours. Medication may include a regimen of non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) if the patient presents within 72 hours. Evaluation at the earliest opportunity can be helpful to examine for anogenital injury and collect forensic evidence (CDC, 2021).

Pennsylvania Code § 21.503 maintains that photographs, medical tests, and X-rays of a suspected victim of child abuse may be taken or requested by an RN, LPN, or CRNP if they are clinically indicated. The medical reports of the images and medical tests are to be sent to the county children and youth social service agency at the time the written report is sent or as soon thereafter as possible, up to 48 hours after the electronic report. This information is also to be made available to law enforcement officials in the course of the investigation (23 Pa.C.S. § 6314 and 6340).

Photographing Evidence

The goal for photographing evidence is to accurately document the findings that serve as a basis for one’s opinion. In Pennsylvania, permission from a parent or guardian is not required prior to taking photographs of suspected child abuse victims (23 Pa. C.S. § 6314).

If photographs will be needed, it is a good idea to inform the child or adolescent and encourage them to participate in the process. Photographs are another form of medical documentation that can provide objective, visual documentation of abuse. There should be a protocol for releasing the photos after a formal request, and a chain of custody may be necessary as well.

CASE

A mother brought her 12-year-old daughter, Haley, to the emergency department. She said that her daughter had been complaining about painful urination and wanted to check if she might have a bladder infection. The triage nurse, Janelle, asked the mother, who appeared to be in the last trimester of pregnancy, to fill out some paperwork while she took the girl to the bathroom for a urine specimen.

Janelle noticed that the daughter appeared fearful and sat in silence while her mother did all of the talking. When they were alone behind closed doors, Janelle asked Haley if there was anything that she wanted to talk about privately. Haley responded by shaking her head no, but Janelle sensed that the girl was holding something back.

Haley was able to produce a clear, pale yellow urine specimen and then followed the nurse to an exam room. Janelle asked her if she had any pain when she urinated, and Haley said yes. The nurse asked her if she had begun menstruating, and the child said she had not.

Janelle brought the mother into the exam room to wait with her daughter. After obtaining a brief history from the mother, the physician ordered a urinalysis. The urinalysis was negative. The doctor did an external genital exam that revealed numerous vesicular lesions on her labia. The child denied any sexual activity. The doctor cultured the lesions for herpes and asked the mother to step into his office to discuss his findings.

Once Janelle and Haley were alone again in the room, the child burst into tears and told the nurse that her mother’s boyfriend had been rubbing his “private” on her and said that if she told anyone, her mother would go to jail. The nurse stopped questioning the child and reported her suspicion of child sexual abuse to ChildLine. The nurse knew that victims of child sexual abuse should only be minimally questioned until they could undergo a forensic interview.

On the following day, Haley was interviewed by a child forensic interview specialist in a child-friendly advocacy center. She and her mother, who was also a victim of child sexual abuse, received counseling for over a year. Following the CPS investigation, the mother’s boyfriend was eventually tried and convicted of sexual abuse.

PROVISIONS AND RESPONSIBILITIES FOR REPORTING SUSPECTED CHILD ABUSE

Who Can or Must Report Child Abuse?

There are two categories of reporters in Pennsylvania: those who must report (mandated) and those who can report (permissive). Mandated reporters have a legal duty to report suspected child abuse and permissive reporters do not. All residents of Pennsylvania are encouraged to report suspected child abuse if they suspect that a child is a victim of abuse or neglect.

Reporters are not expected to validate their suspicions prior to reporting. The basis for making a report should be on one's evaluation of the circumstances, observations, and familiarity with the family or pattern of events (PA Medical Society, 2020).

PA MANDATED REPORTERS

All of the following persons are mandated reporters in Pennsylvania if they are at least 18 years of age, and they must make a report directly to ChildLine or the Child Welfare Information System if they suspect abuse. Mandated reporters include:

- A person who is licensed or certified to practice in any health-related field under the jurisdiction of the Department of State

- Medical examiner, coroner, or funeral director

- Employee of a healthcare facility or provider licensed by the Department of Health who is engaged in the admission, examination, care, or treatment of individuals

- School employee

- Employee of a childcare service who has direct contact with children in the course of employment

- Clergyman, priest, rabbi, minister, Christian Science practitioner, religious healer, or spiritual leader of any regularly established church or other religious organization

- Individual paid or unpaid who, on the basis of the individual’s role as an integral part of a regularly scheduled program, activity, or service, is a person responsible for the child’s welfare or has direct contact with children

- Employee of a social services agency who has direct contact with children in the course of employment

- Peace officer or law enforcement official

- Emergency medical services provider certified by the Department of Health

- Employee of a public library who has direct contact with children in the course of employment

- Individual supervised or managed by a person listed under numbers (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), (8), (9), (10), (11), and (13), who has direct contact with children in the course of employment

- An independent contractor

- Attorney affiliated with an agency, institution, organization, or other entity, including a school or regularly established religious organization, that is responsible for the care, supervision, guidance, or control of children

- Foster parent

- An adult family member who is a person responsible for the child’s welfare and provides services to a child in a family living home, community home for individuals with an intellectual disability, or host home for children which are subject to supervision or licensure under the Public Welfare Code

(23 Pa. C.S. § 6311)

The above list of mandated reporters in Pennsylvania includes youth camp directors, youth athletic coaches, directors and trainers, all Department of Public Health (DPH) employees, and certain employees of the Office of Early Childhood (OEC). School employees formerly reported to their administration and now must report directly to ChildLine.

The reporting requirements affect school employees, staff at child-care and medical facilities, librarians, and volunteers who work in youth sports, church groups, or other organized youth activities.

Concerns about client confidentiality and other issues resulted in limiting the category of attorneys who are mandated to report to those who work for a school, church, or other organization with responsibility for “the care, guidance, control, or supervision of children.”

CASE

Since his parents divorced when he was 8 years old, Riley, the youngest of four children, has spent every other week at his father’s apartment without his siblings so that he and his father could have “one-on-one time.”

By the age of 9, Riley began exhibiting signs of anxiety and anger. The boy’s teacher, Shondra Williams, noticed that he was late to school and that he arrived to school with no lunch on the days he spent at his father’s. In addition, he complained of a stomachache every day and asked the school nurse to call his mother. On several occasions he tried to leave school and run home as soon as his father dropped him off, but was always seen by the staff.

When Riley came to school one day with sutures on the back of his hand, Mrs. Williams asked him to tell her what had happened. He said that his father had locked him outside in his underwear, so he punched the window to get in and cut his hand. Later that day, as Riley sat alone without eating at lunchtime, Mrs. Williams asked him privately if there was enough food in the home in order to determine if the family might need assistance. Riley told her that his father said he was fat and didn’t need any lunch.

Mrs. Williams, a mandated reporter, believed there was reasonable cause for her to suspect abuse. She conferred with the school administration and then called ChildLine to report her concerns about Riley.

An investigation revealed that Riley was having severe separation anxiety from his mother and siblings. His father’s apartment was filled with storage items, and there was no bed at the residence for Riley, who slept on a mat on the floor. There was also no food in the refrigerator, regarding which Riley’s father had stated that the child was “too fat and that he did not want to keep any food around.”

Riley was screened in to Child Protective Services (CPS) because he was diagnosed with a severe anxiety disorder by the school psychologist. A multidisciplinary team helped Riley and his family. Riley began seeing the school counselor, and at the recommendation of CPS, his visitation schedule was amended to exclude overnights with his father. In addition, his father was ordered by the court to attend parenting classes. Riley’s symptoms improved within a few months after counseling, treatment with anti-anxiety medication, and the revised visitation schedule.

When Must a Report Be Made?

If any mandated reporter as listed under 23 Pa. C.S. § 6311 has reason to suspect that a child is or has been abused, they are required to report their suspicions immediately by phone to 800-932-0313 or electronically through the Child Welfare Portal. Mandated reporters need only to have a reasonable cause to suspect abuse and do not need to investigate the facts, identify the person responsible for the child abuse, or determine if the alleged abuser can be legally classified as a perpetrator.

The mandated reporter must make a report if they:

- Come into contact with the child in the course of employment, occupation, and practice of a profession or through a regularly scheduled program, activity, or service

- Are directly responsible for the care, supervision, guidance, or training of the child, or are affiliated with an agency, institution, organization, school, regularly established church or religious organization, or other entity that is directly responsible

- Are the recipient of a specific disclosure that an identifiable child is the victim of child abuse

- Are the recipient of a specific disclosure by an individual 14 years of age or older that the individual has committed child abuse

(23 Pa. C.S. § 6311)

It is important to note that under 23 Pa. C.S. § 6311:

- A child is not required to come before the mandated reporter in order for the mandated reporter to make a report of suspected child abuse.

- The mandated reporter is not required to identify the person responsible for the child abuse in order to make a report of suspected child abuse.

- A person who has reasonable cause to suspect a child is a victim of child abuse is not required to consider the exclusions from child abuse in order to make a report of suspected child abuse.

Whenever a mandated reporter who is a member of the staff of a medical or other public or private institution, school, facility, or agency makes a report, they are also required to immediately notify the person in charge of the institution. That person or the designated agent must then facilitate the cooperation of the institution with the investigation of the report.

Mandated reporters who work for agencies/organizations subject to supervision by PA DHS must also be trained on internal policies related to reporting suspected child abuse and are encouraged to receive such training from their employers.

How Is a Report Made?

The report can be made verbally by calling ChildLine toll free at 800-932-0313, or it may be filed electronically using the Child Welfare Information Solution (CWIS) online at https://www.compass.state.pa.us/cwis/public/home.

A confirmation by DHS of the receipt of the report of suspected child abuse submitted electronically shall relieve the person making the report of making an additional oral/verbal or written report of suspected child abuse.

If the immediate report is verbal, it must be followed up with a written report or an electronic report (Form CY-47) within 48 hours. However, the failure of a mandated reporter to file form CY-47) shall not relieve the county agency from any duty under the PA CPSL, and the county agency shall proceed as though the mandated reporter complied.

CY-47 forms can be found online at the official website of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on the Keep Kids Safe page (report child abuse) found at https://www.pa.gov/en/agencies/dhs/resources/keep-kids-safe/report-child-abuse.html. This page also has useful phone numbers and instructions.

Permissive reporters are concerned individuals who do not fall under the category of mandated reporters. They are encouraged to report suspected child abuse, but they are not required by law to do so. Permissive reporters need only to call ChildLine’s toll-free number to make a verbal report of suspected abuse; they do not need to follow their phone call with a written report (PA DHS, n.d.).

(See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

What Is Included in the Report?

When calling ChildLine and also at the time of submitting an electronic report, the reporter will be asked to provide the following information, if known. However, it is not required to provide all items in order to report suspected abuse.

- Names and addresses of the child, the child’s parents, and any other person responsible for the child’s welfare

- Where the suspected abuse occurred

- Age and sex of each subject of the report

- Nature and extent of the suspected child abuse, including any evidence of prior abuse to the child or any sibling of the child

- Name and relationship of each individual responsible for causing the suspected abuse and any evidence of prior abuse by each individual

- Family composition

- Source of the report

- Name, telephone number, and email address of the person making the report

- Actions taken by the person making the report, including those actions taken under sections 6314 (relating to photographs, medical tests, and X-rays of child subject to report), 6315 (relating to taking a child into protective custody), 6316 (relating to admission to private and public hospitals), or 6317 (relating to mandatory reporting and postmortem investigation of deaths)

- Any other information required by federal law or regulation

- Any other information that the department requires by regulations

(23 Pa. C.S. § 6313b)

REPORTING REQUIREMENTS AND OTHER LAWS

Mandated reporters often express reluctance to report child abuse because they are concerned they may compromise patient privacy under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) or Pennsylvania’s Mental Health Procedures Act. However, provisions of these acts do not affect the responsibilities of mandated reporters as they are defined in the CPSL. The CPSL instructs mandated reporters that the obligation to report overrides laws that protect the confidentiality of privileged communications of healthcare professionals. The CPSL also prevails over mental health regulations, including the Mental Health Procedures Act, although there are some specific limitations to disclosure for releasing information pertaining to drug and alcohol treatment programs (23 Pa. C.S. § 6311.1, § 5100.38).

What Happens After a Report Is Made?

When a county agency or law enforcement receives a referral/report, the county agency or law enforcement official is to notify DHS/ChildLine after ensuring the immediate safety of the child and any other child(ren) in the child’s home.

ChildLine will immediately evaluate and transmit oral or electronic reports they receive to the appropriate county agency or law enforcement officials.

- If a person identified falls under the definition of perpetrator, ChildLine will refer the report to the appropriate county agency for an investigation.

- If the person identified is not a perpetrator and the behavior reported includes a violation of a crime, ChildLine will refer the report to law enforcement officials.

- If a person identified falls under the definition of perpetrator and the behavior reported includes a criminal violation, ChildLine will refer the report to both the appropriate county agency and law enforcement officials.

- If a report indicates that a child may be in need of other protective services, ChildLine will refer the report to the proper county agency to assess the needs of the child and provide services, when appropriate.

In cases of a CPS report, the county Children and Youth Agency must begin an investigation within 24 hours. The investigation is thorough and determines whether or not the child was abused and what services are most appropriate for the child. The investigation must be completed within 30 days unless the agency can justify a delay because of the need for further information, such as medical records or interviews of the subjects of the report.

Mandatory Notification of Substance-Affected Infants

Under Pennsylvania law (23 Pa. C.S. § 6386), a healthcare provider involved in the delivery or care of a child under 1 year of age is required to immediately notify the Department of Human Services of the Commonwealth if the provider has determined, based on standards of professional practice, that the child was born affected by:

- Substance use or withdrawal symptoms resulting from prenatal drug exposure, or

- A fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

Notification to the Department can be made to ChildLine, electronically through the Child Welfare Portal, or at 800-932-0313. This notification is for the purpose of assessing a child and the child's family for a plan of safe care and does not constitute a child abuse report.

HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS REQUIRED TO REPORT

Healthcare providers required to submit this notification include licensed hospitals or healthcare facilities or persons who are licensed, certified, or otherwise regulated to provide healthcare services in Pennsylvania, including a physician, podiatrist, optometrist, psychologist, physical therapist, certified nurse practitioner, registered nurse, nurse midwife, physician’s assistant, chiropractor, dentist, pharmacist, or an individual accredited or certified to provide behavioral health services.

PLAN OF SAFE CARE

After notification of a child born affected by substance use or withdrawal symptoms resulting from prenatal drug exposure or a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder:

- A multidisciplinary team meeting must be held prior to the child’s discharge from the healthcare facility.

- The meeting will inform an assessment of the needs of the child and the child’s parents and immediate caregivers to determine the most appropriate lead agency for developing, implementing, and monitoring a plan of safe care.

- The child’s parents and immediate caregivers must be engaged to identify the need for access to treatment for any substance use disorder or other physical or behavioral health condition that may impact the safety, early childhood development, and well-being of the child.

- Depending upon the needs of the child and parent(s)/caregiver(s), ongoing involvement of the county agency may not be required.

For the purpose of informing the plan of safe care, the multidisciplinary team may include public health agencies, maternal and child health agencies, home visitation programs, substance use disorder prevention and treatment providers, mental health providers, public and private children and youth agencies, early intervention and developmental services, courts, local education agencies, managed care organizations, private insurers, hospitals, and medical providers.

Protections to Reporters

One of the identifiable factors that deters reporting is fear of retaliation. Therefore, as described in the CPSL (23 Pa.C.S. § 6318), a person, hospital, institution, school, facility, agency, or agency employee acting in good faith is considered immune from civil and criminal liability that might otherwise result from any of the following:

- Making a report of suspected child abuse or making a referral for general protective services, regardless of whether the report is required to be made under the PA CPSL

- Cooperating or consulting with an investigation under the PA CPSL, including providing information to a child fatality or near-fatality review team

- Testifying in a proceeding arising out of an instance of suspected child abuse or general protective services

- Engaging in any action authorized under 23 Pa.C.S. § 6314 (relating to photographs, medical tests and X-rays of child subject to report), § 6315 (relating to taking child into protective custody), § 6316 (relating to admission to private and public hospitals), or § 6317 (relating to mandatory reporting and postmortem investigation of deaths)