What All Nurses Need to Know About Pregnant and Postpartum Patients

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

This continuing nursing education course is designed for all nurses who provide care to pregnant or postpartum patients, regardless of specialty or practice setting. Whether you work in emergency care, medical-surgical units, primary care, community health, or obstetrics, understanding the unique complications associated with pregnancy and the postpartum period is essential to ensuring timely, effective, and safe patient care.

Course Price: $18.00

Contact Hours: 2

Course updated on

October 2, 2025

"From start to finish, it took me two hours to complete, and I consider myself a fast reader and good comprehender of information. Knowing how that can differ greatly from person to person, I think these courses are all very on target as far as content and hours awarded. Thank you." - Amy, RN in Kansas

"Excellent course. Very organized, highlighting important concepts about each pregnancy complication. Thank you!" - Loretta, RN in California

"The case studies were an excellent contribution to understanding the content." - Rose, RN in New Mexico

"Excellent course. Concise and compact. Perfect for experienced RNs in Family Practice and Urgent Care/ER. Thank you!" - Pamela Mansfield RN, Triage Nurse in Urgent Care in Washington

What All Nurses Need to Know About Pregnant and Postpartum Patients

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will be able to identify the possible complications and implications for care for the pregnant and postpartum patient. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Identify urgent maternal warning signs indicating possible pregnancy complications.

- Describe the patient care considerations in response to pregnancy-related bleeding complications.

- Identify signs of pregnancy-related hypertension.

- Summarize potential impacts due to gestational diabetes.

- Name the risk factors that can contribute to amniotic membrane rupture.

- Discuss issues related to preterm labor and birth.

- List the most common postpartum complications.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Recognizing Signs of Pregnancy-Related Complications

- Pregnancy-Related Bleeding Complications

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum

- Pregnancy-Related Hypertensive Complications

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

- Amniotic Membrane Complications

- Preterm Labor and Birth

- Postpartum Complications

- Conclusion

- Resources

- References

RECOGNIZING SIGNS OF PREGNANCY-RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Nurses encounter pregnant and postpartum patients in a wide variety of settings, including primary care offices, emergency departments, urgent care clinics, mental health settings, obstetric offices, schools, and more.

All reproductive-aged patients should be verbally screened for current or recent pregnancy. Screening may include asking, “Are you currently pregnant, or have you been pregnant within the last year?” If the response is yes, this should alert the nurse that a patient complaint or finding could be related to the current or past pregnancy.

It is also important for nurses to be able to recognize signs and symptoms of pregnancy-related complications in order to provide appropriate care. Nurses must be familiar with the maternal and fetal implications, medical treatment and management, and nursing care necessary to address a wide range of pregnancy-related complications. They must also educate patients about warning signs and how to respond.

According to the CDC (2024a), to improve patient care and outcomes related to pregnancy-related complications, healthcare providers can:

- Ask questions to better understand their patient and things that may be affecting their lives

- Help patients, and those accompanying them, understand the urgent maternal warning signs and when to seek medical attention right away

- Help patients manage chronic conditions or conditions that may arise during pregnancy, like hypertension, diabetes, or depression

- Respond to any concerns patients may have

- Provide all patients with respectful quality care

The most prevalent complications that arise during pregnancy include:

- Anemia

- Depression

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Fetal problems

- Gestational diabetes

- High blood pressure

- Hyperemesis gravidarum

- Infections

- Miscarriage

- Placenta previa

- Placental abruption

- Preeclampsia

- Preterm labor

(Office on Women’s Health, 2025)

| Sign/Symptom | Pregnancy-Related Cause or Risk |

|---|---|

| (AIM, 2022) | |

| Headache that won’t go away or gets worse over time |

|

| Dizziness or fainting |

|

| Changes in vision |

|

| Fever of 100.4 °F or higher |

|

| Extreme swelling of hands and face |

|

| Thoughts of harming self or baby |

|

| Trouble breathing |

|

| Chest pain or fast-beating heart |

|

| Severe nausea and vomiting (not like morning sickness) |

|

| Severe belly pain that doesn’t go away |

|

| Baby’s movement stopping or slowing down during pregnancy |

|

| Swelling, redness, or pain of the leg |

|

| Vaginal bleeding or fluid leaking during pregnancy |

|

| Heavy vaginal bleeding or discharge after pregnancy |

|

| Overwhelming tiredness |

|

PREGNANCY-RELATED BLEEDING COMPLICATIONS

Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy must always be investigated, particularly if it is enough blood to drop into the toilet or to warrant use of a menstrual pad. Bleeding can indicate pregnancy loss, placenta previa, placental abruption, ectopic pregnancy, or gestational trophoblastic disease. Events that may result in a small amount of bleeding (perhaps seen on toilet paper after voiding) due to cervical irritation include recent vaginal intercourse or recent cervical exam.

Pregnancy Loss

Pregnancy loss (also referred to as spontaneous abortion or miscarriage) is defined as a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy up to 20 weeks’ gestation (Prager et al., 2025a). This loss occurs without intervention from the patient or another person.

Pregnancy loss affects 10% to 31% of pregnancies (Prager et al., 2025b). Risk for pregnancy loss increases with increasing maternal age and prior pregnancy loss. Pregnancy loss can be caused by a number of other factors, including chromosomal abnormalities, maternal infection, maternal endocrine disorders (e.g., hypothyroidism, uncontrolled diabetes), reproductive system abnormalities (e.g., cervical insufficiency), substance use, environmental factors (exposure to toxins and pollutants), and maternal injury.

NURSING CARE

The primary nursing intervention for all types of pregnancy loss is to ensure patient safety by identifying and controlling any bleeding and hemorrhagic shock. Symptoms of hemorrhagic shock include an increased heart rate, decreased blood pressure, cool and clammy skin, lightheadedness, and confusion. The nurse should anticipate the need for oxygen therapy and fluid and blood replacement. Patients should be blood typed and cross-matched in case blood transfusion is necessary.

Pregnancy loss may be managed expectantly, with medication, or with surgery. Medication administration may include misoprostol (Cytotec) with or without the use of a prior dose of methotrexate. Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin that causes the cervix to soften and dilate and induces uterine contractions. It may be used to help in expelling the pregnancy tissue or to control bleeding. Methotrexate halts a pregnancy’s development by blocking the use of folic acid.

The nurse monitors the patient’s vital signs, oxygen saturation, intake and output, and laboratory results according to institutional policies. If a patient experiences a threatened abortion but the fetus does not die, the nurse may be responsible for monitoring fetal heart sounds and the overall well-being of the fetus depending on gestational age. The nurse should administer prescribed anti-D-immune globulin (human) (RhoGAM) to Rh-negative patients within 72 hours to prevent alloimmunization (an immune response to the fetus’s blood cells).

RhoGAM

RhoGAM should be given to Rh-negative patients at approximately 28 weeks’ gestation, within 72 hours of the birth of an Rh-positive baby, and with the possibility of maternal fetal hemorrhage (such as trauma to the abdomen during pregnancy, after an ectopic pregnancy, bleeding during pregnancy, after a pregnancy loss or induced abortion, after attempt at cephalic version, and after invasive procedures [e.g., amniocentesis]).

COMPLICATIONS

Two serious complications of missed abortions are infection and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Infection can occur as a result of carrying an expired fetus and is a serious health threat to these patients. DIC produces clotting, bleeding, and ischemia that occur simultaneously. Symptoms include sudden shortness of breath, chest pain, and/or cyanosis. Bleeding from the nose, gums, and IV sites, as well as petechiae, also occur in the presence of DIC. Treatment is aimed at delivering the fetus and placenta, which will stop the overactivation of the clotting process. Patients are treated with oxygen therapy and are usually given blood products.

Ectopic Pregnancy

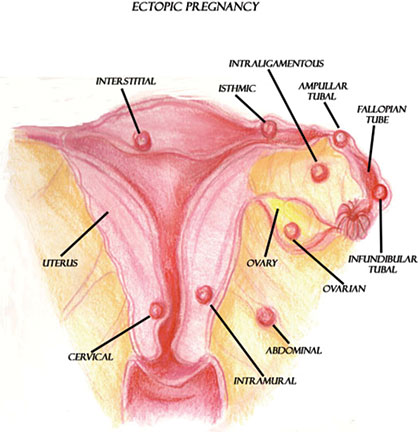

Ectopic pregnancies occur when the ovum is fertilized by the sperm but implants at a site other than the endometrium of the uterus. Ninety-six percent of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tubes (Tulandi, 2025b). Other possible implantation sites include the cervix, ovary, or abdominal cavity.

Possible implantation sites for ectopic pregnancies. (Illustration courtesy of Sim London Jr.)

Ectopic pregnancies are caused by a variety of factors, which include anything that would prevent or slow the fertilized ovum’s journey to the lining of the uterus. More specifically, anything that causes scarring in or blocks the fallopian tubes may cause an ectopic pregnancy. This can be due to infection, surgery, congenital anomalies, or tumors (Tulandi, 2025b).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Signs and symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy include vaginal bleeding, lack of menstruation (amenorrhea), and abdominal pain. However, other disease processes (e.g., pregnancy loss) may be responsible for such symptoms. Transvaginal ultrasound and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) laboratory testing are necessary to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy.

The outcome of an ectopic pregnancy depends on the location of implantation. The ovum may naturally reabsorb into the body, or the structure supporting the ovum may rupture. If the implantation site is a fallopian tube, the tube may rupture and cause internal hemorrhaging and hypovolemic shock, which is a life-threatening event for the patient.

Signs and symptoms of a ruptured fallopian tube include vaginal bleeding; severe abdominal pain or pelvic, shoulder, or neck pain (as a result of blood leaking out of the fallopian tube and irritating the diaphragm); weakness; dizziness; decreased blood pressure; and increased pulse. It is important to note that many patients experiencing an ectopic pregnancy are asymptomatic prior to tubal rupture.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

An ectopic pregnancy implanted in a fallopian tube requires either pharmacologic or surgical management. Pharmacologic management with methotrexate is indicated if the tube is unruptured, the ectopic pregnancy is less than 3 to 4 cm, there is no fetal cardiac activity, and the patient is stable hemodynamically. Methotrexate is an antimetabolite chemotherapeutic agent that stops cells from dividing and thus stops the gestation. Methotrexate treatment is usually performed on an outpatient basis. Renal and liver function tests should be confirmed before administering methotrexate due to possible toxicity issues (Tulandi, 2025a).

Surgical management includes salpingostomy and salpingectomy. Salpingostomy requires a small linear incision in the tube to remove the pregnancy tissue. This protects the tube for a future pregnancy. A salpingectomy involves the removal of the affected fallopian tube.

NURSING CARE

The nurse caring for a patient experiencing an ectopic pregnancy observes for changes in the patient’s blood pressure and pulse, which could indicate hypovolemic shock resulting from hemorrhage. Regular assessment of vaginal bleeding is also essential. Rh-negative patients require administration of prescribed RhoGAM to prevent alloimmunization. Finally, the nurse is responsible for monitoring and controlling pain levels.

If salpingostomy or salpingectomy is performed, the nurse monitors vital signs, oxygen saturation, intake and output, and laboratory results according to institutional policies. As with all patients experiencing a pregnancy loss, it is important for the nurse to recognize the loss and to provide resources to assist the patient in coping with the emotions that accompany the experience of an ectopic pregnancy.

GESTATIONAL TROPHOBLASTIC DISEASE (GTD)

Gestational trophoblastic disease, most commonly the hydatidiform mole or molar pregnancy, occurs when the chorionic villi of the placenta increase as a result of genetic abnormalities. The villi swell, forming fluid-filled sacs, which have the appearance of tiny clusters of grapes within the uterus.

Patients with GTD exhibit light to heavy bleeding and even hemorrhage. Bleeding can be bright red or watery and brown, appearing similar to prune juice. Anemia may result due to bleeding. Additionally, as a result of the proliferation of tissues and the presence of clotted blood, the uterus may appear larger than expected for gestational age. Despite an enlarged uterus, fetal heart tones and movement are absent. Serum hCG levels are also increased, and patients may experience hyperemesis.

Molar tissues are removed by surgical uterine evacuation. Intravenous oxytocin is usually administered to contract the uterus during suction evacuation to increase uterine tone and decrease blood loss.

Patients are followed for one year after removal of a molar pregnancy to detect choriocarcinoma, or cancer associated with GTD. If serum hCG levels do not return to prepregnancy levels, there is a possibility that choriocarcinoma may be present, and further investigation is necessary. Therefore, it is essential that patients understand the need for follow up.

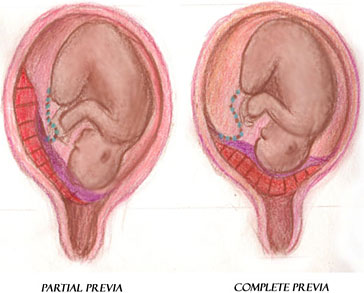

Placenta Previa

Placenta previa is the complete or partial covering of the internal os of the cervix by the placenta (see illustration). Placenta previa occurs when the placenta implants in the lower portion of the uterus near the internal cervical os. Previas are classified according to the degree to which they cover the os. Specifically, if the lower border of the placenta is less than 2 cm to the internal cervical os but not covering the os, the placenta is considered low lying.

Placenta previa with partial covering of the internal os (left) and placenta previa with complete covering of the internal os (right). (Illustration courtesy of Sim London Jr.)

As the pregnancy nears term and the cervix dilates, the placenta implanted near or over the internal cervical os is disrupted and bleeding can occur. The bleeding places the patient and fetus at risk. The major factors that place patients at risk for a placenta previa include previous placenta previa, previous cesarean delivery (risk increases with an increasing number of cesarean deliveries), and multiple gestation (Lockwood & Russo-Stieglitz, 2025a).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The most significantly recognized symptom of placenta previa is painless, bright red vaginal bleeding or hemorrhage during late pregnancy. However, bleeding may not occur until labor begins. If there is a diagnosis or high suspicion of placenta previa, it is imperative that vaginal examinations be avoided, because stimulation of the placenta may cause hemorrhage. The bleeding as a result of placenta previa could cause the patient to hemorrhage and go into shock, and the fetus could experience hypoxia and possibly death from maternal bleeding.

As a result of the abnormally implanted placenta, the fetus is often in a transverse or breech position, which may be noted during fundal examination.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

As previously mentioned, vaginal examination must be avoided if a patient presents with painless, bright red vaginal bleeding because hemorrhage may occur. A transabdominal ultrasound can be performed to diagnose the previa. It may be followed by a transvaginal ultrasound in order to better visualize the cervix and placenta. Medical management of a placenta previa is largely determined by gestational age, fetal status, amount of bleeding, and type of previa.

Some patients may deliver vaginally if they are near term, the cervix is ripe, the previa is not total, the fetal heart tracing does not show fetal compromise, and there is minimal bleeding. However, if heart tracings indicate fetal compromise, significant bleeding, or hemorrhage or a complete previa is present, a cesarean section is usually necessary.

NURSING CARE

Nursing care for patients hospitalized with a placenta previa involves close monitoring of bleeding as well as fetal and maternal status. Significant bleeding or hemorrhage should be quantified and reported immediately to the appropriate healthcare provider. Careful monitoring of bleeding is imperative, as vital sign changes may not be initially evident. Regular assessment of fetal heart rate (FHR) and movement is necessary. Heart rate patterns that indicate fetal compromise (i.e., recurrent late or prolonged decelerations, absent or marked FHR variability) should be reported to the healthcare practitioner immediately.

Nonstress testing to evaluate fetal status is performed during bleeding episodes according to medical orders or institutional policy. Patients should be blood typed and cross-matched in case a blood transfusion is necessary. Blood loss should be quantified. Intravenous access should be maintained for prompt administration of fluids or blood products.

Anti-D-immune globulin (RhoGAM) is given to Rh-negative patients during each bleeding episode to prevent alloimmunization. If bleeding episodes are within three weeks of administration, readministration is not necessary (Lockwood & Russo-Stieglitz, 2025b).

Placental Abruption

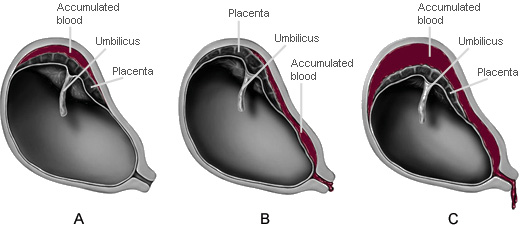

Placental abruption, often referred to as an abruption or abruptio placentae, is the premature separation of the normally implanted placenta from the uterine wall before delivery of the fetus. It is considered an obstetrical emergency. Bleeding occurs between the uterine wall and the placenta.

Placental abruption is a potentially life-threatening event for the patient and the fetus, depending on the severity of the abruption. Patients with an abruption are at risk for developing hypovolemic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and possibly death. Since the placenta is the source of oxygenation for the fetus, premature separation of the placenta from the uterine wall can place the fetus at great risk for hypoxia and death.

Placental abruption is classified according to the degree of placental separation and subsequent hemorrhage. An abruption can be partial or complete, with apparent or concealed hemorrhage (see illustrations). An abruption is partial if a section of the placenta separates from the uterine wall but a portion of the placenta remains attached. A complete abruption, the most emergent form, occurs when the entire placenta detaches from the uterine wall. Apparent hemorrhage refers to bleeding that is evident, while a concealed hemorrhage denotes bleeding that is obscured.

A. Partial placental abruption with concealed hemorrhage

B. Partial placental abruption with apparent hemorrhage

C. Complete placental abruption with apparent hemorrhage

(Illustrations by Jason McAlexander. © Wild Iris Medical Education.)

Aside from abruptions occurring as a result of trauma, the causes of placental abruption are largely unknown. However, there are several factors that place patients at risk for an abruption, including the strongest risk factors of previous abruption, hypertension, cocaine use, cigarette smoking, and genetic factors (Ananth & Kinzler, 2025).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The classic signs and symptoms of placental abruption include an abrupt onset of vaginal bleeding, which may be dark red due to old blood from a concealed abruption; uterine tenderness; and a boardlike abdomen. Patients often complain of an aching or dull pain in the abdomen or lower back. Additionally, frequent uterine contractions with poor uterine resting tone (the baseline pressure of the uterus between contractions) are frequently noted.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Placental abruption is usually diagnosed by abdominal ultrasound in addition to the presenting signs and symptoms. Treatment is based on the degree of placental separation and subsequent hemorrhage as well as the status of the patient and fetus. In the presence of severe abruption and hemorrhage, emergency cesarean section is performed unless delivery is imminent.

NURSING CARE

Although vaginal delivery is preferred to cesarean section for patients who are hemodynamically stable, the nurse must be prepared to deal with the possibility of severe hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock, as well as the resulting fetal distress. Intravenous access with a large-bore catheter is placed to accommodate the administration of fluid and blood products.

It is necessary to monitor carefully the status of the patient and fetus. Frequent vital signs and fetal heart tones, as well as monitoring and documentation of blood loss, are essential. Maternal bleeding may be indicated by falling hemoglobin and hematocrit or abnormal CBC (complete blood count). Abnormal vital signs, bleeding, or fetal heart patterns indicating fetal compromise should be reported immediately to the appropriate healthcare provider. Observation and documentation of the patient’s intake and output and pain and comfort levels are also essential. Patients should be blood typed and cross-matched in case a blood transfusion is necessary. RhoGAM is indicated for Rh-negative patients. Fetal distress may be indicated by electronic fetal monitoring changes, such as tachycardia followed by bradycardia, absent variability, decelerations, and/or sinusoidal tracing.

Because the potential for patient and fetal injury is high in the presence of placental abruption, it is important to address the emotional needs of the patient. Patients should be kept informed of the status of the fetus, and the nurse should be available and ready to answer any questions that patients or their families may have.

| Assessment | Placenta Previa | Placental Abruption |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Painless | Uterine tenderness; severe abdominal pain and possibly aching or dull pain in the lower back |

| Bleeding | Bright red | May be concealed; if noted, it is often dark red |

| Uterus | No unusual contractions or irritability | “Boardlike” abdomen; uterine irritability with poor resting tone |

| Risk for postpartum hemorrhage | High risk; due to low placement of the placenta, there is limited uterine contraction | High risk due to poor contractility of the uterus following an abruption |

HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

Nausea and/or vomiting occur normally during pregnancy and can affect up to 90% of pregnancies. Symptoms often start at 5 to 6 weeks’ gestation and usually subside by 20 weeks. Dietary changes can help alleviate the symptoms. These include eating before or as soon as feeling hungry; additional snacks; small, frequent meals; avoiding triggers; and consuming ginger. Nausea and vomiting that develop after 10 weeks’ gestation may also be caused by conditions unrelated to pregnancy (e.g., gastrointestinal disorders) and should be investigated (Smith et al., 2025a, 2025b).

Nausea and vomiting that occurs regularly beyond 20 weeks’ gestation and involves vomiting more than three times per day, weight loss >3 kg or 5% of prepregnancy body weight, and ketonuria is termed hyperemesis gravidarum, or severe, persistent nausea and vomiting.

Signs and Symptoms

Normal first-trimester nausea and vomiting can be challenging for pregnant women. However, patients with hyperemesis gravidarum are frequently debilitated by unrelenting vomiting and dry retching. Common signs and symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum include:

- Poor appetite

- Poor nutritional intake

- Vomiting beyond 20 weeks’ gestation

- Significant weight loss (>5% of prepregnancy weight)

- Ketonuria unrelated to other causes

- Dehydration (dry mouth and mucous membranes, decreased skin elasticity [turgor], and dark, concentrated urine)

Medical Treatment

When diagnosing hyperemesis gravidarum, it is important to investigate the underlying causes of nausea and vomiting. These causes can include gastroenteritis, pancreatitis, hepatitis, peptic ulcer disease, and pyelonephritis. Patients usually require intravenous fluids and antiemetics to manage hyperemesis. While most care for hyperemesis is provided in the patient’s home, some patients may require hospitalization for nutritional support via enteral or parenteral access.

Nursing Care

Nurse caring for patients with hyperemesis gravidarum includes monitoring and providing physical care as well as psychosocial support. The nurse will administer IV fluids and antiemetics. Intake and output are carefully monitored, as well as gastrointestinal status. Laboratory results (e.g., ketones, electrolytes, complete blood count, liver enzymes) are carefully monitored, with abnormal results reported to the appropriate healthcare practitioner. It is also important to monitor for weight loss since the constant, prolonged nausea and vomiting associated with hyperemesis may easily result in malnutrition for pregnant patients.

Often patients are unable to work or tend to activities of daily living. This underscores the need for the nurse to address the psychosocial needs of patients, which may involve simply listening to the patient or a referral to appropriate resources.

PREGNANCY-RELATED HYPERTENSIVE COMPLICATIONS

Gestational hypertension is defined as hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) on at least two occasions at least four hours apart occurring for the first time at ≥20 weeks’ gestation. The diagnosis also requires normal urine protein excretion for pregnancy and absence of signs and symptoms of end-organ dysfunction associated with preeclampsia with severe features. It is characterized by a blood pressure that returns to normal by 12 weeks postpartum. Gestational hypertension is a provisional diagnosis; if the patient has proteinuria or new signs of end-organ dysfunction, then the diagnosis is instead preeclampsia. Gestational hypertension may also progress to preeclampsia (Melvin & Funai, 2025).

Preeclampsia is identified by the above gestational hypertension blood pressure parameters (or systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg on one occasion) in the presence of protein in the urine (proteinuria). Preeclampsia with severe features is identified by the above preeclampsia in addition to end-organ dysfunction (characterized by low platelets, increased protein creatinine ratio, pulmonary edema, elevated liver function tests, visual changes, and headache) (August, 2025).

Eclampsia is the occurrence of generalized seizures in the presence of preeclampsia without other known cause for the seizures. Seizures can occur any time before, during, or after delivery of the fetus.

Chronic hypertension is defined by a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg on at least two occasions that is present prior to pregnancy, presents before the 20th week of pregnancy, or persists longer than 12 weeks postpartum.

Preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension is diagnosed in a patient with chronic hypertension who develops worsening hypertension with new-onset proteinuria or other features of preeclampsia (e.g., elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) (August, 2025).

Pathophysiology

Vasospasm in the arterioles of patients with gestational hypertension causes increased blood pressure and a decrease in placenta and uterine perfusion. Renal blood flow is reduced, along with the renal glomerular filtration rate, which produces proteinuria. Headaches and visual disturbances are the result of cellular damage and cerebral edema caused by central nervous system changes in the presence of hypertension. Liver enlargement is the result of hepatic changes that lead to epigastric pain. Generalized vasospasm causes endothelial cell damage, which triggers coagulation pathways, and subsequently abnormalities in bleeding and clotting can occur.

Maternal and Fetal Implications

Hypertension during pregnancy places patients and their fetuses at great risk for a variety of complications. Some of the most significant maternal complications of hypertension in pregnancy include cerebral vascular accident (CVA, or stroke), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and placental abruption from the elevated blood pressure.

Additionally, patients are at risk for the development of HELLP syndrome, likely a severe form of preeclampsia. Just as its name implies, HELLP syndrome causes great dysfunction within the body and requires immediate intervention. It is characterized by:

- Hemolysis of red blood cells, which leads to anemia

- Elevated liver enzymes, leading to epigastric pain

- Low platelets, which cause abnormal bleeding and clotting as well as petechiae

Patients with HELLP syndrome whose function continues to decline without intervention can develop eclampsia and are at risk for DIC, placental abruption, acute renal failure, pulmonary edema, liver hematoma/rupture, and retinal detachment (Sibai, 2025). Fetal complications derive from placental abruptions, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm birth resulting from decreased placenta perfusion.

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment for patients with gestational hypertension greatly depends on the severity of hypertension and the gestational age of the fetus, as well as the potential risk to the patient and fetus.

During early pregnancy, outpatient management is usually appropriate; these patients are monitored at home for blood pressure, proteinuria, and other signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and may be prescribed oral antihypertensives. Regular fetal monitoring is necessary to evaluate fetal well-being.

Severe hypertension requires immediate intervention with intravenous medications such as labetalol and/or hydralazine. Glucocorticoids may be administered to enhance fetal lung maturity. Low-dose aspirin started prior to 20 weeks’ gestation for patients with average or high risk of developing preeclampsia may be given to decrease the likelihood of developing preeclampsia or its subsequent placental and fetal effects (Melvin & Funai, 2025).

Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) may be prescribed during labor and delivery to prevent seizures and for fetal/neonatal neuroprotection in pregnancies between 24 and 32 weeks’ gestation. Magnesium sulfate is not used to control hypertension. Magnesium sulfate is administered intravenously via an infusion delivery device during delivery and for 24 hours postdelivery. Since MgSO4 can cause respiratory depression in the neonate, arrangements are made for specialized neonatal care.

Nursing Care

Gestational hypertension presents a great risk to patients and their fetuses. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the nurse to monitor the patient carefully for signs of a decline in health status. The nurse should immediately report increases in blood pressure, visual disturbances, severe headaches, epigastric pain, and oliguria to the appropriate healthcare practitioner.

In the presence of eclampsia, the nurse must be prepared to prevent injury to the patient during seizures and to monitor seizure activity. Bedside rails should be up and padded. Emergency equipment should be readily available, including oxygen, a nonrebreather face mask, and emergency medication.

In the event of a seizure, patients should be protected from injury. The nurse should note the beginning and ending of the seizure and ensure adequate oxygenation after seizure activity has ceased. The nurse should not attempt to insert any object into the mouth during a seizure. The patient should be placed in a lateral position if possible, or the head gently turned to the side to prevent the aspiration of mucus and emesis into the lungs during seizure activity. The nurse may provide oxygen by nonrebreather mask. The nurse obtains vital signs and monitors the fetus following the seizure.

Labor may progress rapidly during seizure activity. Sometimes newborns are delivered suddenly during a seizure. The nurse should be prepared for an imminent delivery in patients with preeclampsia and eclampsia.

CASE

Eden, a 16-year-old, comes to the urgent care clinic because she is certain she has a respiratory illness. She is pregnant for the first time, with twins, and is in her 37th week of gestation. When her name is called, she rushes in to the examination room, saying, “I’m so glad to see you. I have this nasty cough, and I also feel like my head is going to explode. My face has gotten fat like my belly. I can’t wait for this whole thing to be over.”

Eden’s vital signs are temperature 98.2 °F, pulse 70, respirations 20, and blood pressure 150/98. Her urine is 2+ for protein. Pitting edema of +2 is noted bilaterally in the lower extremities. The fetal heart rates are in the 150s for both fetuses. She has a productive cough and crackles in the bases of both lungs. Eden’s mother usually attends prenatal appointments and has talked in the past about the seizures she experienced when she was pregnant with Eden.

Discussion

In addition to a respiratory workup, Eden is assessed thoroughly for complications associated with gestational hypertension. She has some risk factors and exhibits several symptoms. Eden is very young, is pregnant with twins, and has a family history of eclampsia. She has proteinuria, facial edema, and edema of the lower extremities.

Eden may be hospitalized on bed rest for evaluation of her condition. Her vital signs will be closely monitored, with attention to fetal well-being; urinary output; and reports of headache, visual disturbances, and epigastric pain. The goals of hospitalization for Eden include prevention of seizure and promotion of a safe delivery. Since Eden is so close to her due date, an induced delivery may be considered.

(Case study courtesy of Sharon Walker, RN, MSN.)

GESTATIONAL DIABETES MELLITUS (GDM)

Gestational diabetes mellitus occurs when a patient’s pancreatic function is not sufficient to overcome the insulin resistance associated with pregnancy. In pregnancy, glucose demands increase as the fetus grows. The “insulin-antagonistic” properties of placental hormones affect the patient by causing normal insulin resistance of pregnancy. This allows a proper supply of glucose for the growing fetus. In gestational diabetes mellitus, the pregnant patient is unable to process glucose sufficiently in the body and hyperglycemia occurs (Durnwald, 2025a).

Individuals who have had GDM are also nearly 10 times as likely to develop type 2 diabetes (Durnwald, 2025b).

Maternal and Fetal Complications

A variety of maternal and fetal complications are associated with GDM.

Infants born to patients with gestational diabetes mellitus are significantly more likely to be macrosomic (birth weight >4.5 kg). This occurs due to fetal hyperinsulinemia as a result of maternal hyperglycemia, which stimulates excessive growth. These large infants may have difficulty maneuvering the birth canal, and a cesarean section may be required. If vaginal delivery is attempted, the infant is at risk for shoulder dystocia and related birth injuries. Patients also have an increased frequency of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, polyhydramnios, and stillbirth.

After delivery, the newborn infant’s blood glucose must be monitored regularly for hypoglycemia due to the sharp decrease in available glucose after the umbilical cord is cut. The newborn’s pancreas continues to produce insulin after delivery despite the decrease in serum glucose. This adds to the potential instability of the infant’s blood glucose. Infants are also at risk for hypocalcemia, hyperbilirubinemia, hypomagnesemia, polycythemia, cardiomyopathy, and respiratory disorders as a result of gestational diabetes (Caughey, 2025).

PREEXISTING DIABETES MELLITUS

In addition to the risks associated with GDM, women with pregestational diabetes mellitus (type 1 or type 2) are at risk for their children to have congenital anomalies related to hyperglycemia during early pregnancy. It is advised to keep diabetes under control for at least three months before trying to conceive.

Medical Treatment

Pregnant patients are routinely screened for GDM at 24 to 28 weeks’ gestation. In order to diagnose gestational diabetes, patients drink 50 grams of oral glucose solution. After one hour, a blood sample is obtained and tested for glucose tolerance. A glucose level of ≥130–140 mg/dL is considered a positive screen, and further investigation is warranted. A three-hour glucose tolerance test (with a 100-gram oral glucose solution) is then typically performed.

Most patients with GDM are treated through diet and exercise. Patients are advised to eat a diet favoring fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and fish and low in red and processed meat, refined grains, and high-fat dairy. Some patients may require insulin or oral hypoglycemia agents to manage gestational diabetes mellitus.

Nursing Care

It is important for the nurse to monitor serum glucose levels throughout the pregnancy of patients with GDM. A referral to a dietitian may also be necessary. The nurse may also conduct regular fetal surveillance, including nonstress tests or biophysical profiles starting at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation and until delivery.

OBESITY IN PREGNANCY

The prevalence of obesity in those of reproductive age is 40%. One quarter of pregnancy complications (e.g., gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, large-for-gestational-age newborns, and preterm birth) are attributable to maternal overweight/obesity (Ramsey & Schenken, 2025). Given the magnitude of this issue, it is imperative that patients be educated about the benefits of diet and exercise during preconception counseling and during the pregnancy.

AMNIOTIC MEMBRANE COMPLICATIONS

Prelabor rupture of membranes (PROM) (previously known as premature rupture of membranes) refers to the rupture of membranes one hour or more before the onset of labor. Labor may be medically induced to reduce the risk of chorioamnionitis (infection of the chorion and amnion of the placenta), which can be life-threatening for the patient and fetus.

Preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM) (previously known as preterm premature rupture of membranes) refers to the rupture of membranes prior to onset of labor in pregnancies approximately less than 37 weeks’ gestation. PPROM is often associated with preterm labor and birth. The most common identifiable risk factor for PPROM is genital tract infection (Duff, 2025a).

PPROM can cause a variety of problems, especially for the fetus. Without the protective barrier of the amniotic membrane, the fetus is at a greater risk for the development of infection and preterm delivery. The fetus is also at risk for becoming septic after delivery. Additionally, without the cushioning of the amniotic fluid, there is a higher probability of umbilical cord compression as well as cord prolapse.

Medical Treatment

The first step in determining the appropriate course of action for patients with possible PROM or PPROM involves distinguishing amniotic fluid from urine or other vaginal discharge. Often, patients complain of a “sudden gush” and/or a continuous or intermittent trickle of fluid from the vagina once the membranes have actually ruptured.

The healthcare practitioner performs a sterile speculum examination to look for pooling of amniotic fluid near the cervix. Fluid may be observed as pooling on a sterile speculum exam. Commercial tests, such as AmniSure and ROM Plus, may be used to test for ruptured membranes. Fluid may also be tested using nitrazine paper as well as via microscopic examination for the presence of ferning (the appearance of a fernlike pattern in a dried specimen of cervical mucus or vaginal fluid, which would indicate the presence of amniotic fluid). Ultrasound examination may be performed to determine the amount of available amniotic fluid after the rupture of membranes.

Medical treatment for patients with PROM or PPROM depends on a variety of factors. Gestational age, fetal lung maturity, available amniotic fluid, and etiology must be considered before deciding on treatment. Patients near term whose labor does not begin spontaneously following the rupture of membranes may be induced if the cervix is ripe. For preterm patients, providers and patients may desire to prolong the pregnancy to promote fetal lung maturity; such patients may be prescribed corticosteroids to promote fetal lung maturity until delivery occurs or until there is a need to induce labor (Duff, 2025b).

Nursing Care

As with medical treatment, nursing care greatly depends on whether the medical diagnosis is PPROM or PROM. However, nursing care typically involves assisting the healthcare practitioner to confirm the rupture of membranes, monitoring the patient for infection and the presence of uterine contractions, and monitoring the status of the fetus. It is imperative that the nurse change patient underpads frequently and avoid unnecessary vaginal examinations to help prevent infection (and with PPROM to avoid decreasing the time until delivery).

When caring for a patient with PPROM or PROM, the nurse should be prepared to address cord prolapse and compression, which can occur as the umbilical cord slips down in the pelvis. This is a life-threatening situation for the fetus; therefore, the fetus must be monitored closely. In the event of cord prolapse and compression, the nurse attempts to relieve pressure on the umbilical cord and instructs the patient to quickly move into the knee-chest or Trendelenburg position. Oxygen is administered, and the healthcare practitioner notified immediately. Emergency cesarean section is likely.

PRETERM LABOR AND BIRTH

Preterm labor refers to labor that occurs after 20 weeks’ but before 37 weeks’ gestation. Preterm birth, a consequence of preterm labor, refers to delivery prior to 37 weeks’ gestation. Preterm birth is a significant contributor to infant mortality rates.

Maternal and Fetal Implications

Preterm labor and birth present a unique challenge to patients and their fetuses. Although most of the implications apply to the fetus, patients may suffer from stress due to the diagnosis of preterm labor and birth as well as from the causative agent. Specifically, patients may be experiencing preterm labor and birth due to conditions such as sepsis or stress.

The fetus is at great risk for delivering early as a result of preterm labor. The effects of preterm labor and birth depend on the gestational age of the fetus at delivery. The immaturity of fetal lungs in the presence of preterm labor and birth is a significant concern.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients presenting with preterm labor and birth often complain of feeling pressure in the pelvic area, abdominal and/or uterine cramping or contractions, painful or painless contractions, feeling as though the fetus is “balling up,” and/or constant back pain. Amniotic membranes may rupture prematurely, and a sudden gush or constant trickle of vaginal fluid may be noted.

Medical Treatment

Clinical criteria for a diagnosis of preterm labor include:

- Persistent uterine contractions (≥6 in 60 minutes) and

- Cervical dilation ≥3 cm or

- Cervical length <20 mm on transvaginal ultrasound or

- Cervical length 20 to 29 mm on transvaginal ultrasound and positive fetal fibronectin (Lockwood, 2025)

Medical treatment for preterm labor and birth depends on the gestational age of the fetus. Generally, healthcare practitioners seek to avoid delivery of patients prior to 34 weeks’ gestation to allow further maturation of the fetal lungs. Glucocorticoids (betamethasone) are often prescribed to increase fetal lung maturity, tocolytics to control uterine contractions and delay birth so that glucocorticoids can take effect, antibiotics for group B streptococcal chemoprophylaxis, and magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection in offspring born preterm (Lockwood, 2025).

Nursing Care

Nursing care for patients experiencing preterm labor includes administering prescribed medications such as antibiotics, glucocorticoids, magnesium sulfate, and tocolytics and preparing the patient for possible delivery. While hospitalized, patients are monitored for signs and symptoms of infection, which can lead to preterm labor. Fetal tachycardia indicates possible infection and should be evaluated immediately. Vital signs, contractions, and fetal status are assessed as ordered or according to institutional policy.

When patients are faced with the possibility of delivering a preterm infant, the situation may quickly become overwhelming to them. Although preterm labor and birth can occur rapidly, it is imperative that nurses address the emotional issues of the patient. Generally, this will involve answering patient questions about the status of the fetus and preparing the patient for the care required to prevent delivery or the necessary preparation for preterm delivery.

POSTPARTUM COMPLICATIONS

Despite the normalcy of childbirth, complications may arise that will have detrimental effects on the postpartum patient. In the week after delivery, leading causes of death included high blood pressure, infection, and severe bleeding. About 33% of maternal deaths happen one week to one year postpartum (CDC, 2024b). Healthcare professionals working with postpartum patients must have a clear understanding of these complications, including the signs and symptoms, nursing interventions, and treatment.

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH)

Postpartum hemorrhage is one of the leading causes of death among postpartum women. Traditionally, PPH has referred to a blood loss of ≥500 mL after a vaginal birth and ≥1,000 mL after a C-section. In 2017, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists revised their definition to be a cumulative blood loss ≥1,000 mL or bleeding associated with signs/symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours of the birth process (ACOG, 2017).

Postpartum hemorrhage is categorized as early or late. Primary or early refers to a hemorrhage occurring within the first 24 hours after birth, while secondary, late, or delayed refers to a hemorrhage occurring 24 hours to 12 weeks after delivery. PPH affects approximately 1% to 3% of deliveries (Belfort, 2025).

CAUSES AND INTERVENTIONS

The most common causes can be remembered by the Four Ts mnemonic:

- Tone: uterine atony

- Trauma: laceration, rupture

- Tissue: retained tissue, blood clots, or placenta accreta spectrum

- Thrombin: coagulopathy

(Belfort, 2025)

Late postpartum hemorrhage is often caused by diffuse uterine atony or subinvolution of the uterus (uterus not returning to its normal size) caused by retained placental fragments and/or infection that prevent the uterus from contracting. In the case of retained placental fragments, clots develop around the retained fragments and hemorrhaging can occur days later when the clots are shed. The certified nurse-midwife or physician is responsible for examining the placenta after delivery and ensuring that it is intact; therefore, a late PPH is usually preventable.

Assessment and manual expression of placental fragments by the physician or nurse-midwife can often alleviate the problem; however, surgical intervention, such as a dilation and evacuation (D&E), may be necessary. With subinvolution and a late PPH, fundal massage, in addition to medications, may be used to minimize bleeding. (The California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative [CMQCC, 2022] has created the OB Hemorrhage Toolkit to assist providers and clinical staff in recognizing and responding to hemorrhage.)

Thrombophlebitis

Patients can suffer from thrombophlebitis as a result of venous stasis and the normal hypercoagulability state of the postpartum period. Thrombophlebitis is an inflammation of the blood vessel wall in which a blood clot forms and causes problems in the superficial or deep veins of the lower extremities or pelvis.

The blood clot that develops in thrombophlebitis can lead to a life-threatening pulmonary embolism as a result of the clot detaching from the vein wall and blocking the pulmonary artery. The major signs of pulmonary embolism include dyspnea and chest pain.

In monitoring postpartum patients for the development or presence of thrombophlebitis, nurses assess for the presence of hot, red, painful, or edematous areas on the lower extremities or groin area. An elevated temperature may also be present. It is contraindicated to assess for a thrombophlebitis by eliciting a Homans’ sign.

Interventions to treat thrombophlebitis depend on the severity of the thrombosis. Usually, for superficial thrombosis, analgesics, bed rest, and elevation of the affected limb are enough to alleviate the problem. However, in the presence of a DVT, anticoagulants may be necessary. In addition to using compression stockings and applying warm, moist heat, patients are instructed to keep their legs elevated and uncrossed and to ambulate only after symptoms subside.

Infections

Postpartum infections are infections accompanied by a temperature of 38 °C (100.4 °F) or higher on any two of the first 10 days postpartum, exclusive of the first 24 hours (when low-grade fever is common and self-limited) (Berens, 2025). Postpartum patients are carefully monitored for signs and symptoms of infection during this period. Common infections that may occur during the postpartum period include mastitis, endometritis, wound infections, and urinary tract infections.

MASTITIS

Lactational mastitis is inflammation of the breast tissues associated with breastfeeding. It can lead to a painful infection of the breast, which can progress to an abscess if not treated properly. It typically presents as a localized red, painful, firm, swollen area of one breast with accompanying fever >38.3 °C. The patient may also complain of myalgia, chills, malaise, and flu-like symptoms (Dixon & Louis-Jacques, 2025).

Mastitis is less likely to occur with complete emptying of the breast and good breastfeeding technique. Thus, it is crucial that postpartum nurses teach breastfeeding patients proper latch-on technique and that they stress regular breastfeeding and allowing the breast to empty completely. Breastfeeding patients are also encouraged to avoid missed feedings and allowing the breast to become engorged.

According to the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (2023), treatment recommendations include:

- Using ice or cold compresses

- Using anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving medications

- Wearing a supportive bra to help swelling

- Avoiding deep massage and squeezing (which will cause injury and make the inflammation worse)

- Not feeding more or expressing more milk on the side with the problem

- Stopping feeding or pumping if no milk is flowing

- Contacting the healthcare provider if not feeling better in 24 hours

If mastitis progresses to infection, antibiotic therapy will likely be prescribed. Breastfeeding may continue while on antibiotics.

ENDOMETRITIS

Endometritis is an infection of the decidua (pregnancy endometrium) characterized by postpartum fever (and resulting tachycardia), midline lower abdominal pain, and uterine tenderness. Malodorous purulent lochia, chills, headache, malaise, and/or anorexia may also be present (Chen, 2025).

Endometritis is usually treated with broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics and rest. Blood cultures to identify the causative organism of endometritis are performed if the patient does not respond to empiric therapy. White blood cell (WBC) counts are monitored. However, it is important to remember that the white blood cell count is normally elevated after delivery for a short period; continued monitoring of the WBC count is required in identifying endometritis and is likely to show a left shift and increasing number of neutrophils.

SURGICAL SITE INFECTIONS

Commonly affected surgical sites during the postpartum period include the perineum, due to lacerations and episiotomies, and C-section incisions. As with all infections, every patient is at risk.

Surgical site infections typically exhibit redness, warmth, poor wound approximation, tenderness, and pain. If untreated, these patients may develop a fever and other symptoms of an infection, such as malaise. Blood cultures may be obtained to isolate the causative organism. Antibiotics will typically be administered, and drainage of the wound may be necessary.

Patients are taught proper handwashing and encouraged to maintain adequate fluid intake and increased protein intake to assist in wound healing. Surgical site infections can be intensely painful, especially in the perineum. Therefore, the nurse assists these patients in managing pain through the use of analgesics and positioning.

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS (UTIs)

The risk of developing a UTI is high during the postpartum period. A woman’s urethra and bladder are often traumatized during labor and birth due to intermittent or continuous catheterizations and the pressure of the infant as it passes through the birth canal. Additionally, the bladder and urethra lose tone after delivery, making the retention of urine and urinary stasis common. Women may also develop urinary retention and subsequent UTI due to epidural anesthesia or vaginal procedures (Berens, 2025).

Patients with urinary tract infections often complain of frequent, urgent, and/or painful urination with suprapubic pain. A low-grade fever and hematuria may also be present. Urinary tract infections are treated with antibiotics, and it is important that these patients drink adequate fluids to flush bacteria out of the system.

Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression is a serious and debilitating depression that affects many women throughout the world. Postpartum depression occurs in approximately 10% to 15% of women after delivery (Viguera, 2025).

Symptoms are generally noted within the first three months but may occur up to a year after delivery. They typically include changes in sleep, energy, appetite, weight, and libido. Other symptoms include lack of energy to the point of not getting out of bed for hours, but this should be distinguished from the normal lack of energy that results from the sleep deprivation of caring for an infant. Additional symptoms include anxiety and irritability; feeling inadequate, overwhelmed, or unable to care for the baby; and nonadherence to postnatal care (Viguera, 2025).

Adverse outcomes of postpartum depression can include impaired bonding, poor nutrition and health in the offspring, interference in the relationship with one’s partner, suicidal ideation, and infanticide (Viguera, 2025).

It is the responsibility of nurses to assess postpartum patients for signs and symptoms of postpartum depression. Various assessment tools are available, including the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). This tool is quick and provides a simple means to assess patients while at the hospital, during postpartum home visits, and during postpartum follow-up clinic visits. This tool can also be used to assess mothers at pediatric follow-up visits. (See “Resources” at the end of this course.)

After screening and assessment, women who are at risk for developing (or who are suffering from) postpartum depression can be referred to the appropriate healthcare professional for follow-up and treatment. Treatment may include a combination of psychotherapy, social support, and medication. Nurses can support these patients in the healing process at follow-up appointments and during home visits, including encouraging adequate nutrition, rest, relaxation, and exercise.

Hypertension

Postpartum hypertension has been seen in as many as 20% of all postpartum individuals within 6 weeks of giving birth. It can be prolonged gestational hypertension/preeclampsia or new onset (August, 2025). Postpartum treatment is similar to treatment during pregnancy with the use of antihypertensives and/or magnesium sulfate (in the setting of preeclampsia). Additionally, furosemide may be used.

CONCLUSION

Pregnancy, labor, birth, and the first year after delivery can be a wondrous time in the lives of many. However, this time can be clouded by a variety of complications that affect the patient and fetus. Fortunately, with early identification and treatment of complications and their side effects, patients and their infants have a greater chance of survival and the potential to thrive after delivery.

Nurses play a special role in ensuring the safety of the patient and fetus during all phases of pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum. They must be knowledgeable about complications that can occur and be ready to act on behalf of the patient and fetus. This is the responsibility and goal of the nurse.

Most hospitals and birthing centers provide evidence-based guidelines for nurses caring for patients experiencing complications during their pregnancies. Nurses must provide comprehensive care that follows the recommendations of their facilities.

RESOURCES

Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

Gestational diabetes (American Diabetes Association)

Gestational trophoblastic disease (National Cancer Institute)

Hyperemesis education and research (HER Foundation)

REFERENCES

Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. (2023). Mastitis in breastfeeding. https://www.bfmed.org/assets/PatientHandouts/English_ABM_Mastitis%20Handout_Protected.pdf

Alliance for the Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM). (2022). Urgent maternal warning signs. https://saferbirth.org/aim-resources/aim-cornerstones/urgent-maternal-warning-signs/

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). (2017). Postpartum hemorrhage (Practice Bulletin 183). https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/articles/2017/10/postpartum-hemorrhage

Ananth CV & Kinzler WL. (2025). Acute placental abruption: Pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnosis, and consequences. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-placental-abruption-pathophysiology-clinical-features-diagnosis-and-consequences

August P. (2025). Treatment of hypertension in pregnant and postpartum patients. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-hypertension-in-pregnant-and-postpartum-patients

Belfort MA. (2025). Overview of postpartum hemorrhage. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-postpartum-hemorrhage

Berens P. (2025). Overview of the postpartum period: Disorders and complications. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-postpartum-period-disorders-and-complications

California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC). (2022). OB hemorrhage toolkit V3.0 errata 7.18.22. https://www.cmqcc.org/toolkits-quality-improvement/hemorrhage

Caughey AB. (2025). Gestational diabetes mellitus: Obstetric issues and management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-diabetes-mellitus-obstetric-issues-and-management

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024a). Working together to reduce Black maternal mortality. https://www.cdc.gov/womens-health/features/maternal-mortality.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024b). Pregnancy-related deaths: Data from maternal mortality review committees in 28 U.S. states, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/data-research/mmrc/

Chen KT. (2025). Postpartum endometritis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/postpartum-endometritis

Dixon JM & Louis-Jacques A. (2025). Lactational mastitis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lactational-mastitis

Duff P. (2025a). Preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/preterm-prelabor-rupture-of-membranes-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

Duff P. (2025b). Preterm prelabor rupture of membranes: Management and outcome. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/preterm-prelabor-rupture-of-membranes-management-and-outcome

Durnwald C. (2025a). Gestational diabetes mellitus: Screening, diagnosis, and prevention. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-diabetes-mellitus-screening-diagnosis-and-prevention

Durnwald C. (2025b). Gestational diabetes mellitus: Glucose management, maternal prognosis, and follow-up. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-diabetes-mellitus-glucose-management-maternal-prognosis-and-follow-up

Lockwood CJ. (2025). Preterm labor: Clinical findings, diagnostic evaluation, and initial treatment. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/preterm-labor-clinical-findings-diagnostic-evaluation-and-initial-treatment

Lockwood CJ & Russo-Stieglitz K. (2025a). Placenta previa: Epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, morbidity and mortality. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/placenta-previa-epidemiology-clinical-features-diagnosis-morbidity-and-mortality

Lockwood CJ & Russo-Stieglitz K. (2025b). Placenta previa: Management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/placenta-previa-management

Melvin LM & Funai EF. (2025). Gestational hypertension. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gestational-hypertension

Office on Women’s Health. (2025). Pregnancy complications. https://www.womenshealth.gov/pregnancy/youre-pregnant-now-what/pregnancy-complications

Prager S, Micks E, & Dalton VK. (2025a). Pregnancy loss (miscarriage): Description of management techniques. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pregnancy-loss-miscarriage-description-of-management-techniques

Prager S, Micks E, & Dalton VK. (2025b). Pregnancy loss (miscarriage): Terminology, risk factors, and etiology. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pregnancy-loss-miscarriage-terminology-risk-factors-and-etiology

Ramsey PS & Schenken RS. (2025). Obesity in pregnancy: Complications and maternal management. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/obesity-in-pregnancy-complications-and-maternal-management

Sibai BM. (2025). HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hellp-syndrome-hemolysis-elevated-liver-enzymes-and-low-platelets

Smith JA, Fox KA, & Clark SM. (2025a). Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Clinical findings and evaluation. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/nausea-and-vomiting-of-pregnancy-clinical-findings-and-evaluation

Smith JA, Fox KA, & Clark SM. (2025b). Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: Treatment and outcome. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/nausea-and-vomiting-of-pregnancy-treatment-and-outcome

Tulandi T. (2025a). Ectopic pregnancy: Choosing a treatment. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ectopic-pregnancy-choosing-a-treatment

Tulandi T. (2025b). Ectopic pregnancy: Epidemiology, risk factors, and anatomic sites. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/ectopic-pregnancy-epidemiology-risk-factors-and-anatomic-sites

Viguera A. (2025). Postpartum unipolar major depression: Epidemiology, clinical features, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/postpartum-unipolar-major-depression-epidemiology-clinical-features-assessment-and-diagnosis

Customer Rating

4.9 / 102 ratings