HIV/AIDS Training for Washington Healthcare Professionals (4 Hours)

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

Washington HIV/AIDS Training. 4-hour continuing education course on HIV/AIDS for healthcare practitioners. Instant online certificate. Start Now!

"Thank you for such an informative course on a sensitive topic. It was very well written." - Michael, student in Washington

"This course was great. I really learned a lot regarding HIV/AIDS and many socioeconomic factors as well." - Shannon, student in Washington

"I learned so much more with this course than I expected. Now I have a new appreciation for these patients." - Yvonne, massage therapist in Washington

"Very thorough and kept my attention." - Cora, medical assistant in Washington

HIV/AIDS Training for Washington Healthcare Professionals (4 Hours)

Copyright © 2023 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this course, you will have increased your knowledge of HIV/AIDS in order to better care for your patients. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Discuss the epidemiology of HIV infection in the United States and in Washington State.

- Explain HIV/AIDS etiology and pathogenesis.

- Summarize the risk factors for transmission of HIV.

- Summarize preventive and control measures for HIV/AIDS.

- Describe psychosocial and mental health issues associated with HIV/AIDS.

- Explain legal and ethical issues pertaining to HIV in Washington State.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The HIV/AIDS pandemic has now been with us for over four decades, and in that span of time, at least 32 million lives have been lost. The pandemic continues to expand in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa (Beyrer, 2021).

A Historical Perspective

In 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) described cases of a rare lung infection and other unusual infections that indicated immune system deficiency in five men, marking the first official reporting of what would later become known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). By the end of that year, there were a total of 337 cases of individuals with severe immune deficiency in the United States—321 adults/adolescents and 16 children under age 13. Of those people, 130 were dead by the end of the year.

In 1982, the CDC used the term AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) for the first time and released the first case definition of AIDS: “A disease at least moderately predictive of a defect in cell-mediated immunity, occurring in a person with no known cause for the diminished resistance to the disease.”

In 1983, the retrovirus human T cell lymphotropic virus type III (later known as human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV) was discovered to be the cause of AIDS. And in 1984 the first diagnostic blood test was developed, the enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA).

By the end of 1985, the United Nations stated that at least one HIV case had been reported from each region of the world.

In 1987, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first medication for treatment for AIDS: AZT (zidovudine), an antiviral drug developed for cancer treatment. In that same year, a new, more specific test for HIV was developed, the Western blot, and in that same year, Universal Precautions were introduced for all healthcare settings.

In 1992, AIDS became the number one cause of death for men in the United States ages 25–44, and in 1995, a world total of 1 million cases of AIDS and an estimated total of 18 million HIV+ adults and 1.5 million HIV+ children were reported globally. The estimated global death toll from AIDS was 9 million.

By 2009, there was a significant decline in new infections during the previous decade, and in 2010, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) announced that a daily dose of HIV drugs reduced the risk of HIV infection, supporting the idea of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a target population.

At the end of 2012, 2.3 million people were newly infected with HIV and 1.6 million died of AIDS. That same year the U.S. FDA approved the first at-home HIV test as well as the use of Truvada for PrEP.

By 2020, an estimated 36.3 million people had died from AIDS-related illness since the start of the epidemic (HIV.gov, 2023a; KFF, 2021; CDC, 2022a).

HIV/AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas Today

As of 2021 in the United States and its six dependent areas, there were more than 1.2 million people living with HIV. In 2020, 30,635 people received an HIV diagnosis—a 17% decrease from the previous year. Among 28,422 persons with HIV infection diagnosed during 2020 in the 46 jurisdictions with complete reporting of laboratory data to the CDC, viral load was suppressed in 67.8% of persons within 6 months of HIV diagnosis.

In 2020, there were 18,489 deaths among adults and adolescents diagnosed with HIV, attributable to any cause, including COVID-19.

Among those who received an HIV diagnosis during 2020, more than 1 in 5 persons (21.6%) received a late-stage diagnosis (AIDS). The highest percentages of late-stage diagnoses occurred among:

- Persons ages 55 and older (37.1%)

- Asians (27.7%)

- Females (23.2%)

The lowest percentages were among:

- Transgender men (5.0%)

- Persons ages 13–24 years (9.1%)

- Black/African Americans (20.0%)

- Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders (20.0%)

The percentage among injection drug users were:

- Females (78.1%)

- Males (77.8%)

(CDC, 2022a)

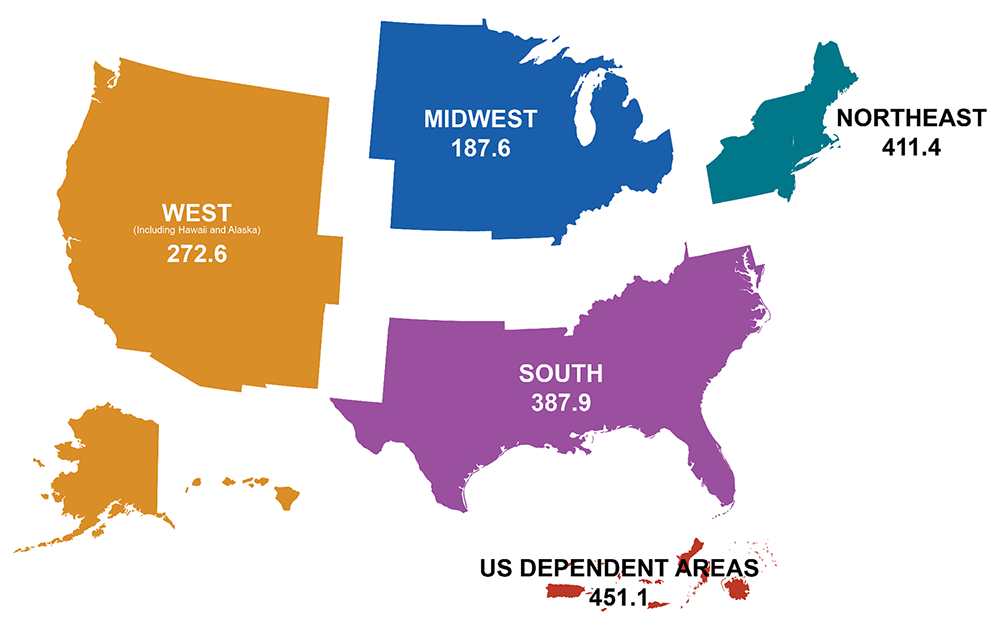

Rates of people with diagnosed HIV in the United States and dependent areas by region of residence, 2021, per 100,000 people. (Source: CDC.)

HIV/AIDS in Washington State

In 2020, there were 14,303 people living with HIV in Washington, and of these, 10,697 (77.1%) were virally suppressed. Of these cases:

- 84.3% male

- 15.7% female

- 16.8% Black

- 16.5% Hispanic/Latinx

- 54.8% White

- 39.1% ages 55 and older

In 2020, there were 421 new HIV diagnoses, the lowest number since 1994. Of these new cases:

- 82.9% male

- 17.1% female

- 19.5% Black

- 17.8% Hispanic/Latinx

- 48% White

- 35.2% ages 25–34

Also in 2020, there were 88 new late-stage HIV infections (AIDS), and of these 20.9% were also newly diagnosed HIV. Of these:

- 83% female

- 17% male

- 23.2% Black

- 17.3% Hispanic/Latinx

- 20.8% White

- 28% ages 25–34

During the year 2020, there were 185 deaths among person with HIV in Washington. Of these:

- 83% male

- 16.3% female

- 10.9% Black

- 13.0% Hispanic/Latinx

- 61.4% White

- 57.6% ages 55 and older

(AIDSVu, 2023; WA DOH, 2021a)

HIV/AIDS ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, spreads via certain body fluids; specifically attacks the CD4, or T cells, of the immune system; and uses those cells to make copies of itself. CD4 cells, also called helper T cells, are a class of white blood cells that help other lymphocytes (memory B cells) that are responsible for producing an antibody to fight infection based on stored data following past exposure to the antibody. As time passes, the virus can destroy enough of these specialized cells that the immune system no longer is able to fight off infections and disease.

HIV is unique among many other viruses because the body is unable to destroy it completely, even with treatment. As a result, once a person is infected with the virus, the person will have it for the remainder of their life (CDC, 2022b).

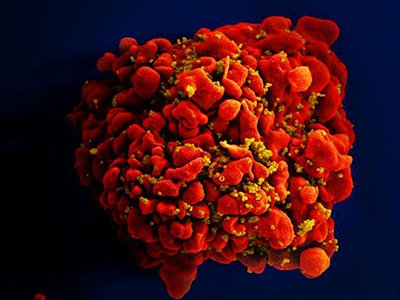

A single T cell (red) infected by numerous, spheroid shaped HIV particles (yellow). (Source: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2012.)

After the initial infection and without treatment, the virus continues to multiply, and over a period of time (which can be 10 years or longer), common opportunistic infections (OIs) begin to take advantage of the body’s very weak immunity. When an opportunistic infection occurs, the person has developed acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Today, OIs are less common in people with HIV because of effective treatment (CDC, 2021a).

Origin and Strains of HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus came from a specific type of chimpanzee in Central Africa and may have jumped from these animals to humans as far back as the late 1800s. The virus has existed in the United States since at least the mid to late 1970s. HIV infection is caused by the HIV-1 or HIV-2 retroviruses in the Retroviridae family, Lentivirus genus.

Of the two main types of human immunodeficiency virus, HIV-1 is the most common; HIV-2 occurs in fewer people. HIV-2 is harder to transmit from one person to another, and it takes longer for the infection to advance to AIDS. Both strains have different groups within them.

HIV-1 includes four groups, with group M responsible for nearly 90% of all HIV-1 cases. This group has nine different strains, and some of these have sub-strains. New strains are being discovered all the time. The B strain is the most common in the United States. The most common HIV strain worldwide is C. The groups N, O, and P are rare outside of west Central Africa.

HIV reproduces carelessly, accumulating many mutations when copying its genetic material, and reproduces at an extremely fast rate. One single virus can produce billions of copies in just a single day (CDC, 2022b; UCB, 2023; Ellis, 2022).

Disease Pathogenesis

The distinguishing characteristic of human immunodeficiency viral infection is the gradual loss of CD4 cells and an imbalance in CD4 cell homeostasis, with progressive impairment of immunity that eventually culminates in death.

HIV is unable to grow or reproduce on its own and depends on a host cell for the raw materials and energy necessary for all the biochemical activities that allow the virus to reproduce. In order to accomplish this, it must locate and bind to a specific type of cell, the CD4 T cell.

The HIV life cycle involves seven stages:

- Binding: HIV attacks a CD4 cell and attaches itself to its protein molecules.

- Fusion: After attaching to the CD4 cell, the HIV viral envelop fuses with the cell membrane, allowing the virus to enter the cell and release HIV RNA and HIV enzymes.

- Reverse transcription: Once inside the cell, HIV releases and uses reverse transcriptase to convert its genetic material (HIV RNA) into HIV DNA, allowing HIV to enter the cell nucleus and combine with the cell’s DNA.

- Integration: Inside the cell’s nucleus, HIV releases integrase, an HIV enzyme, to insert its viral DNA into the DNA of the host cell.

- Replication: When the virus is integrated into the host cell DNA, it begins to use the machinery of the cell to create long chains of HIV proteins, building blocks for more HIV. This results in the death of the CD4 cell.

- Assembly: During assembly, new HIV RNA and HIV proteins made by the host cell move to the surface and assemble into immature noninfectious HIV.

- Budding: Immature HIV pushes itself out of the host cell and releases an enzyme that breaks up the protein chains in the immature virus, creating the mature infectious virus.

When the mature infectious virus enters the bloodstream, the new virus repeats the process, further depleting the CD4 count and effectively reducing immunity (NIH, 2021).

HIV TRANSMISSION AND RISK FACTORS

An individual can only become infected with HIV through direct contact with certain body fluids from a person with HIV who has a detectable viral load. A detectable viral load is having more than 200 copies of HIV in a milliliter of blood.

Transmission Routes

Body fluids known to transmit HIV include:

- Blood

- Semen and preseminal fluids

- Rectal fluids

- Vaginal fluids

- Breast milk

In addition, any body fluid visibly contaminated with blood should be considered capable of transmitting HIV. These fluids may include:

- Cerebrospinal

- Amniotic

- Pleural

- Synovial

- Peritoneal

- Pericardial

For transmission to occur, the virus must enter the bloodstream of an HIV-negative person through a mucous membrane. These are located in the:

- Rectum

- Vagina

- Mouth

- Tip of the penis

The virus can also be transmitted through open cuts or sores or through direct injection (e.g., by a needle or syringe).

Unless blood is visibly present, HIV cannot be transmitted by:

- Saliva

- Sputum

- Sweat

- Tears

- Feces

- Nasal secretions

- Urine

- Vomitus

HIV also cannot be transmitted by:

- Air

- Water

- Donating blood

- Closed-mouth kissing

- Insects

- Pets

- Sharing food or drinks

- Sharing toilets

The main routes of HIV transmission are through:

- Unprotected sexual contact with an infected person

- Sharing needles and syringes with an infected person

- From an infected mother to child during pregnancy, during birth, or after birth while breastfeeding

Additional criteria for HIV transmission to occur include:

- HIV must be present in sufficient transmittable amounts.

- HIV must be able to enter the bloodstream of the next person.

HIV is a fragile entity and cannot survive for a substantial amount of time in the open air. The length of time HIV can survive outside the body is dependent on the amount of virus present in the body fluid and the conditions the fluid is subjected to. Studies have shown that when a high level of HIV that has been grown in a lab is placed on a surface, it loses most of its ability to infect (90%–99%) within several hours, indicating that contact with dried blood, semen, or other fluids poses little risk (HIV.gov, 2022a; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023).

SEXUAL CONTACT

HIV transmission rates vary by the type of sexual contact. The chances of contracting HIV after one exposure are highest among those who have receptive anal sex (about 1%). This means that someone can get the virus 1 out of every 100 times they have receptive anal sex without a condom. The reason for the higher risk of transmission by anal sex is due to the thin layer and easy penetrability of the cells in the anus compared to the vagina. HIV probability is lower for those having insertive anal sex, followed by receptive and insertive vaginal sex. With all three types of sex, the odds of contracting HIV after one exposure are well below 1% (Watson, 2022).

HIV acquisition rates among uncircumcised males are higher than for circumcised males. This may be related to a high density of HIV target cells in the male foreskin, including Langerhans cells and macrophages. Circumcision reduces the risk of female-to-male HIV transmission by 50%–60%; however, circumcision does not appear to decrease the risk of HIV transmission to the partner (Cohen, 2022).

INJECTION DRUG USE

Sharing injection needles, syringes, and other paraphernalia with an HIV-infected person can send HIV (as well as hepatitis B and C viruses and other bloodborne diseases) directly into the user’s bloodstream. About 1 in 10 new HIV diagnoses in the United States is attributed to injection drug use or the combination of male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use. The risk is high because needles, syringes, or other injection equipment may be contaminated with blood, which can survive in a used syringe for up to 42 days, depending on temperature and other factors. HIV-negative persons have a 1 in 160 chance of getting HIV every time they use a needle that has been used by someone else who has HIV. Sharing syringes is the second riskiest behavior following receptive anal sex (CDC, 2021b).

BLOOD TRANSFUSION

The chances that donated blood will contain HIV is less than 1 in nearly 2 million. While all blood donations are screened for HIV before they enter the blood pool, all laboratory tests have a “window period” in which very recent HIV infections cannot be detected, and in those most sensitive assays that are used by blood collection agencies, this window may be between 10–16 days. Because of this, a small number of infected samples still make it through testing (Tufts Medical Center, 2022).

TATTOOING, BODY PIERCING

There are no known cases in the United States of anyone becoming infected with HIV from professional tattooing or body piercing. There is, theoretically, a potential risk, especially during the time period when healing is taking place. It is also possible to become infected by HIV from a reused or not properly sterilized tattoo or piercing needle or other equipment, or from contaminated ink. The risk is very low but increases when the person doing the procedure is not properly trained and licensed (CDC, 2022b).

MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION

Before effective treatment was available, about 25% of pregnant mothers with HIV passed the virus to their babies. Today, if the mother is receiving HIV treatment and has a sustained undetectable viral load through pregnancy and postpartum, the risk of passing HIV to the baby is less than 1%. The risk of HIV transmission while breastfeeding is also less than 1% for women with HIV on antiretroviral therapy with sustained undetectable viral load through pregnancy and postpartum (USDHHS, 2021; NIH, 2023).

At Risk Populations and Behaviors

HIV does not discriminate. Anyone can become infected with the virus. However, there are certain groups of people who are more likely to get HIV than others. This is due to factors such as the communities in which they live, what subpopulation they belong to, and any risky behaviors they become involved in.

COMMUNITIES

Communities at high risk for the spread of HIV are very diverse and can include college campuses, the military, gay neighborhoods, crack houses, prisons, bathhouses, brothels, neighborhoods with homeless people, and “shooting galleries” (locations where intravenous drug users can rent or borrow needles and syringes). The level of risk within these communities varies; however, HIV usually spreads rapidly due to the existence of tightly linked networks connected through sexual behavior and the use of drugs (NAS, 2023).

MEN WHO HAVE SEX WITH MEN

Men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately at risk for HIV infection. In the United States, the estimated lifetime risk for HIV infection among MSM is 1 in 6, compared with 1 in 524 among heterosexual men and 1 in 253 among heterosexual women. These inequalities are further intensified by race and ethnicity, with African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx MSM having a 1 in 2 and a 1 in 4 lifetime risk, respectively (CDC, 2021c).

RACIAL AND ETHNIC MINORITIES

In comparison to their percentage of the population, some groups have higher rates of HIV infection in their communities, which raises the risk of new infections with each sexual or injection drug use encounter.

In 2019, Black/African American people represented 13% of the U.S. population but 40% of those with HIV. Hispanic/Latinx people represented 18.5% of the population but 25% of people with HIV. Black women are overly affected by HIV as compared to women of other races/ethnicities, with the rate of new infections 11 times that of White women and four times that of Latina women. This unequal impact on these communities is also apparent in the incidence of new HIV infections and shows that effective prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching people who could benefit the most.

Additionally, among these groups, a range of social, economic, and demographic factors—such as stigma, discrimination, income, education, and geographic region—affect risk for HIV. These factors help to explain why African Americans have worse outcomes on the HIV continuum of care, including lower rates of linkage to care and viral suppression (HIV.gov, 2023a; CDC, 2023a).

PERSONS WHO INJECT DRUGS

People who inject drugs account for about 1 in 10 HIV diagnoses in the United States. An individual who is HIV-negative has a 1 in 160 chance of getting HIV each time they use a needle that has been used by someone with HIV. Sharing syringes is the second-riskiest behavior for infection with HIV.

Using drugs itself can also increase risk for HIV infection. People who are under the influence of a substance are more apt to engage in risky sexual behaviors, such as having unprotected anal or vaginal sex, having multiple sex partners, or trading sex for money or drugs (CDC, 2022c).

PERSONS WHO EXCHANGE SEX FOR MONEY OR NONMONETARY ITEMS

This group includes a broad range of individuals who trade sex for income or other items such as food, drugs, medicine, and shelter. They are at higher risk for HIV because they are more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors and substance use. Those who exchange sex more regularly as a source of ongoing income are at higher risk than those who do so infrequently. This includes those working as escorts, in massage parlors, in brothels, in the adult film industry, as state-regulated prostitutes (in Nevada), and anyone trading sex to meet their basic needs. For any of these people, sex can be consensual or nonconsensual (CDC, 2022d).

INCARCERATED PERSONS

More than 2 million people in the United States are incarcerated in federal, state, and local correctional facilities on any given day. Prisoners are five times more likely to be infected with HIV than other populations. Only 7% of incarcerated people are women, and HIV prevalence among women in prison is 4% compared to 3% in men.

One reason incarcerated people are at higher risk of HIV involves the difficulty in obtaining clean injecting or tattooing equipment in prisons, since having a needle is often a punishable offence. Therefore, people share equipment to take drugs or tattoo other prisoners, and this is one of the primary causes of HIV infection in prisons.

Sex is also often forbidden in prisons, but it does happen. Prevalence of sexual activity is largely unknown and considered to be significantly underreported due to denial, fear of stigma, and homophobia. In addition, condoms are often not available to prisoners. This means sexual activity is most often unprotected (Be in the Know, 2023a).

OLDER ADULTS

In the United States, HIV infection in both women and men ages 50 and older is most commonly acquired through heterosexual transmission. Certain age-related issues may cause older females to be at higher risk for HIV acquisition, such as vulvovaginal atrophy. Aging females are also less likely to use a condom to prevent pregnancy, which puts them at risk for HIV acquisition if they enter a new sexual partnership.

Injection drug use is also an important but less common risk factor. Twenty-four percent of HIV-negative people ages 50 or older who inject drugs used a syringe that someone else had used (Greene, 2023).

WOMEN AND GIRLS

Nearly 1 in 5 U.S. women has been raped in her lifetime, and 2 in 5 women have experienced another type of sexual assault. Violence against females plays a role in transmitting HIV infection. Types of violence include forced sex and sexual abuse in childhood. Forced sex can cause tears or cuts, allowing easy entry of HIV. This is especially true for girls and younger women whose reproductive tracts are not fully developed. Additionally, the male may not use a condom while engaging in sexual violence. Sexual abuse in childhood raises the lifetime risk of HIV infection, and women who were sexually abused are more likely to report risk-taking behaviors later in life (OWH, 2021).

ADOLESCENTS

Most adolescents ages 13 and older infected with HIV acquired it through sexual activity. Young male adolescents who have sex with men account for 82% of new HIV infections in this age group. Although most adolescents acquire HIV infection through sexual activity, there remains a small proportion who were infected prenatally.

Black adolescents accounted for an estimated 52% of all new HIV infections among this population, followed by Hispanic/Latinx (25%) and White (18%). Geographically, southern states have the greatest percentage (>50%) of adolescents affected by HIV.

The CDC reports that 48% of adolescents reported not using a condom the last time they had sex, and 8% had been physically forced to have sexual intercourse when they did not want to. Data show a decline in sexual risk behaviors among high school students, with fewer students currently being sexually active and fewer having ever had sex (30%).

Among LGBTQ+ adolescents, 1 in 5 experienced sexual violence compared to 1 in 10 of their heterosexual peers. LGBTQ+ adolescents (21%) were also more likely to have ever used illegal drugs than heterosexual students (12.7%) (CDC, 2023b, 2019; Gillespie, 2023).

TRANSGENDER PERSONS

In 2022, over 1.6 million adults (ages 18 and older) and youth (ages 14–17) identified as transgender in the United States. In 2019, transgender people made up 2% of new HIV diagnoses. Studies have found that transgender women have 39 times the odds of being infected with HIV compared to the general population. Transgender men also have higher rates of infection.

Risk factors that may contribute to high infection rates include higher rates of sexual violence, drug and alcohol abuse, sex work, incarceration, homelessness, attempted suicide, unemployment, lack of familial support, violence and sexual violence, stigma and discrimination, limited healthcare access, and negative healthcare encounters (HRCF, 2022; Herman et al., 2022).

Other Factors Affecting Transmission Risk

Many other factors, alone or in combination, affect the risk of HIV transmission.

HIGH VIRAL LOAD

The higher someone’s HIV viral load, the more likely the person is to transmit HIV. Viral load is highest during the acute phase of HIV and without HIV treatment.

- A high HIV viral load is generally considered to be above 100,000 copies per milliliter of blood, but a person could have 1 million or more. At this point the virus is at work making copies of itself and the disease may progress quickly.

- A lower viral load is below 10,000 copies per milliliter of blood. At this point, the virus isn’t actively reproducing as fast and damage to the immune system may be slowed.

- An undetectable viral load is generally considered to be less than 20 copies per milliliter of blood. At this point the virus is suppressed. This does not mean, however, that there is no virus in the body; it just means there is not enough for the test to detect and count. People with HIV who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV sexually to their partners.

(IAPAC, 2021)

OTHER SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES/INFECTIONS (STDs/STIs)

People who have a sexually transmitted disease (also called sexually transmitted infection [STI]) may be at an increased risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV. Some of the most common STDs include gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, trichomoniasis, human papillomavirus (HPV), genital herpes, and hepatitis.

One reason for this is that the behaviors that put people at risk for one infection often put them at risk for others. When a person with HIV acquires another STD such as gonorrhea or syphilis, it is likely they were having sex without using condoms. Also, STDs and HIV tend to be linked, and when someone gets an STD, it indicates they may have acquired it from someone who may be at risk for other STDs as well as HIV.

People with HIV are more likely to shed the virus when they have urethritis or a genital ulcer, and in a sexual partner, a sore or inflammation caused by an STD may allow infection that would have normally been stopped by intact skin. Even STDs that cause no breaks or open sores can increase the risk by causing inflammation that increases the number of cells that can serve as targets for HIV.

Both syphilis and HIV are highly concentrated among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM). In 2021, MSM only and men who have sex with both men and women accounted for 63% of all primary and secondary syphilis cases in which the sex of the partner was known. HIV is more closely linked to gonorrhea than chlamydia (common among young women), and herpes simplex (HSV-2) is commonly associated with HIV. Studies have shown that persons infected with herpes are at three-times higher risk for acquiring HIV infection (CDC, 2023c).

HIV PREVENTION AND RISK REDUCTION STRATEGIES

HIV is preventable. Nevertheless, new infections continue to occur despite the knowledge available about how the virus is transmitted and the means to prevent its transmission or acquisition.

Individual Risk Reduction

A patient’s individual HIV risk can be determined through risk screening based on self-reported behavioral risk and clinical signs or symptoms. In addition to an assessment of behavioral risk, a comprehensive STI and HIV risk assessment includes screening for HIV and STIs. After a sexual history has been obtained, all providers can encourage risk reduction by offering prevention counseling to all sexually active adolescents and to all adults who have received an STD diagnosis, have had an STD during the prior year, or who have had multiple sex partners. Such counseling can reduce behaviors that result in higher risk of HIV infection.

ASSESSING BEHAVIORAL RISKS

Behavioral risks can be identified either through open-ended questions by the provider or through screening questions (e.g., a self-administered questionnaire). An example of an open-ended question is: “What are you doing now or what have you done in the past that you think may put you at risk of HIV infection?”

Common risk assessment questions can include:

- Have you or your sexual partner(s) had other sexual partners in the past year?

- Have you ever had a sexually transmitted infection?

- Are you pregnant or considering becoming pregnant?

- Have you or your sexual partner(s) injected drugs or other substances and/or shared needles or syringes with another person?

- Have you ever had sex with a male partner who has had sex with another male?

- Have you ever had sex with a person who is HIV infected?

- Have you ever been paid for sex (e.g., money, drugs) and/or had sex with a prostitute/sex worker?

- Have you engaged in behavior resulting in blood-to-blood contact (e.g., S&M, tattooing, piercing)?

- Have you been the victim of rape, date rape, or sexual abuse?

- Have you had unprotected anal or vaginal sex?

- How do you identify your gender (male, female, trans, other)?

(Skidmore College, 2023)

PREVENTION COUNSELING AND BEHAVIORAL STRATEGIES

Studies have shown that risk reduction and prevention counseling decreases the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV. Counseling can range from brief messages, to group-based strategies, to high-intensity behavioral discussions tailored to the person’s risk. It is most effective if provided in a manner appropriate to the patient’s culture, language, sex and gender identity, sexual orientation, age, and developmental level. Client-centered counseling and motivational interviewing can also be effective. Training in these methods is available through the National Network of STD Prevention Centers (see also “Resources” at the end of this course) (CDC, 2021f).

Healthcare providers can counsel patients in behavioral strategies to prevent the spread of HIV infection, including:

- Sexual abstinence, since not having oral, vaginal, or anal sex is the only 100% effective option to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV

- Limiting the number of sex partners, since the more sex partners one has, the more likely one of them has poorly controlled HIV or has a partner with an STI

- Condom use, since using condoms correctly and every time when engaging in sexual activity will reduce HIV transmission risk as well as that of other STIs (see box below)

- For women who are unable to convince their partners to use a condom, assessing other barrier methods

- HIV testing, both for the patient and their partner(s)

- Screening and treatment for STDs, due to the shared risk factors for HIV and other STDs

- Stopping injection drug use, or if unable to stop injecting drugs, using only sterile drug injection equipment and rinse water and never sharing equipment with others

- Circumcision, which has demonstrated efficacy in reducing risk among heterosexual men

For people who inject drugs, additional risk reduction interventions can include:

- Voluntary opioid substitution or buprenorphine-naltrexone therapy and participation in needle exchange programs, which has been found to decrease illicit opioid use, injection use, and sharing injection equipment

- Participating in needle exchange or supervised injection programs, which have been found to decrease needle reuse and sharing and to increase safe disposal of syringes and more hygienic injection practices

(HIV.gov, 2023f)

CONDOMS AND THEIR CORRECT USE

To reduce the risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, a male (external) condom or a female (internal) condom for each sexual contact can be used. A male condom is a thin layer of latex, polyurethane (plastic) worn over the penis during sex. A female condom is a thin pouch made of synthetic latex designed to be worn in the vagina during sex. Condoms provide the best protection against HIV.

Do’s of condom use include:

- Do use a condom every time you have sex.

- Do put on a condom prior to having sex.

- Do read the package and check the expiration data.

- Do make sure there are no tears or defects.

- Do store condoms in a cool, dry place.

- Do use latex or polyurethane condoms.

- Do use water-based or silicone-based lubricant to prevent breakage.

Don’t’s of condom use include:

- Don’t store condoms in a wallet, as heat and friction can damage them.

- Don’t use nonoxynol-9 (a spermicide), which can cause irritation.

- Don’t use oil-based products like baby oil, lotion, petroleum jelly, or cooking oil, as they may cause the condom to break.

- Don’t use more than one condom at a time.

- Don’t reuse a condom.

(CDC, 2022f)

Antiretroviral-Based Prevention Strategies

In addition to behavioral strategies, antiretroviral-based strategies have proven highly effective in preventing and reducing HIV transmission.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is for adults who are not infected by HIV but who are at high risk of becoming infected. As a part of PrEP, ART medication is taken consistently every day to reduce the risk of HIV infection through sexual contact.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) involves taking ART medication to prevent HIV infection after a recent exposure. PEP must be started within 72 hours after a possible exposure and taken daily for 28 days (CDC, 2023e).

For couples in which one is HIV infected and the other uninfected (i.e., serodiscordant), recommendations include:

- Initiation of ART in the infected partner in order to prevent transmission to the uninfected partner; PrEP for the uninfected partner

- Continued use of condoms even when the infected partner has achieved viral suppression and the risk of HIV transmission is negligible, in order to reduce the risk of STD transmission and in case there is a failure in viral suppression

The risk of transmitting HIV from mother to child can be 1% or less if the mother takes HIV treatment as prescribed throughout pregnancy and delivery and the baby is given HIV medications for 2–6 weeks following birth. If the mother’s viral load is not low enough, a cesarean delivery can help prevent HIV transmission. Antiretroviral treatment also can reduce the risks of transmitting HIV through breast milk to less than 1% (CDC, 2023f).

Reducing Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens

In the United States from 1985 to 2013, a total of 58 confirmed and 150 possible cases of occupational transmission of HIV were reported. Only one of those confirmed cases occurred after 1999. Of the 58 confirmed cases, 49 resulted from a percutaneous cut or puncture. From 2000 onward, occupationally acquired HIV infection in the United States has become exceedingly rare, a finding that supports the efficacy of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) (Spach & Kalapila, 2023).

UNIVERSAL PRECAUTIONS AND STANDARD PRECAUTIONS

Universal Precautions were introduced and then mandated by OSHA in the early 1990s to protect both patients and healthcare staff members. The CDC expanded the concept of Universal Precautions by incorporating major safeguard features of the past into a new set of safety measures. These expanded measures are termed Standard Precautions. Regardless of a patient’s infection status, Standard Precautions must be used in the care of all patients to protect staff from the elements of blood, any body fluids, and secretions and excretions. These precautions include diligent hand hygiene and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (Broussard & Kahwaji, 2022; OSHA, 2021).

Washington Administrative Code (WAC) 296-823 mandates that the rules for Safety Standards be followed for occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens as adopted under the Washington Industrial Safety and Health Act of 1973 (Chapter 49.17 RCW) and as enforced by the Department of Labor and Industries Division of Occupational Safety and Health.

EXPOSURE CONTROL PLAN (ECP)

Under WAC 296-823, each employer covered must develop and implement a written exposure control plan and training that contains the following elements:

- A plan for protecting employees from risk of exposure to blood or other potentially infectious materials (OPIM)

- Training to employees about risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens and ways to protect themselves

- Additional training when tasks or procedures are added or changed that affect an employee’s occupational exposure

- Maintaining training records

- Making the hepatitis B vaccination available to employees

- Using feasible controls to eliminate or minimize occupational exposure to blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM)

- Using controls, including appropriate equipment and safer medical devices, to eliminate or minimize occupational exposure

- Making sure items are appropriately labeled

- Prohibiting food, drink, and other personal activities in the work area

- Prohibiting pipetting or suctioning by mouth

- Handling regulated waste properly and safely

- Providing and ensuring personal protective equipment is used when work practices and controls will not fully protect employees from risk of exposure

- Ensuring employees who have been exposed to blood or other potentially infectious materials (OPIM) have appropriate post-exposure evaluation and follow-up available

- Establishing and maintaining medical records and recording all occupational injuries resulting from contaminated needle sticks or cuts from contaminated sharps

- Implementing and enforcing additional rules in research laboratories and production facilities engaged in the culture, production, concentration, experimentation, and manipulation of HIV and HBV

(Washington State Legislature, 2020a)

BLOODBORNE PATHOGENS STANDARD TRAINING

In 1991, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) introduced and published the Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens Standard, designed to protect workers in healthcare and related occupations from risk of exposure to bloodborne pathogens such as HIV and HBV. In Washington State, all new employees or employees being transferred into jobs involving tasks or activities with potential exposure to blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM) must receive training in accordance with WAC 296-823-120 prior to taking on those tasks (Washington State Legislature, 2020a).

Full details for training requirements are found in the Washington Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens, Chapter 296-823 WAC. (See “Resources” at the end of this course.)

EMPLOYER PROTOCOL FOR MANAGING OCCUPATIONAL EXPOSURES

If a healthcare worker experiences an HIV exposure in the workplace, the person should follow OSHA’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030), which requires employers to make immediate confidential medical evaluation and follow-up available at no cost to workers who have an exposure incident. Management of exposure requirements include:

- Initial management. The first response is to cleanse the area thoroughly with soap and water. For punctures and small lacerations, the area is cleaned with alcohol-based hand hygiene. Exposed mucous membranes are irrigated copiously with water or saline.

- HIV testing. Healthcare personnel should immediately report a possible exposure to the occupational health department so the source patient can be screened for HIV as soon as possible.

- Offering post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP):

- If the source has known HIV infection

- When the HIV status of the source patient is unknown, while awaiting HIV testing results, particularly if the source patient has symptoms consistent with acute HIV infection or is at high risk for HIV infection

- If the source cannot be identified

(Zachary, 2023)

WASHINGTON STATE POST-EXPOSURE REQUIREMENTS

Washington State Department of Labor & Industries, Chapter 296-823 WAC, Occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens post-exposure requirements, include:

- Making a confidential medical evaluation and follow-up available to employees who experience an exposure incident

- Testing the blood of the source person

- Providing the results of the source person’s blood test to exposed employee

- Collecting and testing the blood of the exposed employee

- Providing information to the healthcare professional evaluating the employee

- Obtaining and providing a copy of the healthcare professional’s written opinion on post-exposure evaluation to the employee

(Washington State Legislature, 2020a)

ADMINISTRATION OF POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS

For most individuals, post-exposure prophylaxis should be started as early as possible, ideally within 1–2 hours. If more than 72 hours have elapsed, PEP is not initiated.

For most individuals, a three-drug regimen is utilized. However, there are special considerations for certain populations, including persons who are or could become pregnant and those persons with reduced kidney function.

PEP is continued for four weeks but can be discontinued if testing shows that the source patient is HIV negative. People receiving PEP are monitored for adverse reactions to the drugs and for drug toxicity.

For all individuals who have had an exposure to HIV, repeat HIV testing with an antibody-antigen test is performed at six weeks and four months post exposure. If an antibody test is used, repeat HIV testing is performed at six weeks, three months, and six months post exposure (Zachary, 2023).

PEPline

Information regarding the most current PEP regimen is available to any clinician from the Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Hotline (PEPline) at 888-448-4911.

The National Clinician Consultation Center provides free consultation and advice based on established guidelines and the latest medical literature on occupational exposure management to clinicians, including:

- Assessing the risk of exposure

- Determining the appropriateness of prescribing PEP

- Selecting the best PEP regimen

- Providing follow-up testing

(NCCC, 2023)

HIV Transmission Prevention in the Home

Patients with HIV, family, and informal caregivers are educated in methods to prevent transmission of bloodborne pathogens in the home and to lower the risk of infection for the person living with HIV.

GLOVES AND HANDWASHING

Disposable gloves (latex, vinyl, or nitrile in case of the latex allergy) are worn if coming into contact with blood or body fluids. Any cuts, sores, or breaks in exposed skin are to be covered. Rubber gloves are worn when cleaning articles soiled with urine, feces, or vomitus, which may all contain nonvisible blood or other infectious material.

When a task is completed, gloves are carefully removed by pulling them off inside-out, one at a time, avoiding contact with any potentially infectious material. Gloves are changed and hands washed as soon as possible. Rubbing the eyes, mouth, or face while wearing gloves must be avoided. Disposable gloves are never washed and reused. Correct handwashing is critically important (Kaiser Permanente, 2022; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023).

HANDLING SHARPS AND SYRINGES

Needles, lancets, and syringes used in the home must be safely handled and disposed of properly. Needles must not be broken off from a syringe. All used sharps and syringes are placed in a safe container with at least a one-inch opening and a lid that will seal tightly, such as an empty plastic laundry detergent container or glass bottle or jar. If a glass jar is used, it is placed in a larger plastic bucket or container that has a tight-fitting lid. Containers are taped shut for added safety and labeled with the warning: “SHARPS, DO NOT RECYCLE!” Such containers are place well out of reach of children. The local health department can provide information on nearby disposal sites.

If needlestick injury does occur, the wound is to be washed with soap and water and medical attention sought as soon as possible for consideration of post-exposure prophylaxis (Kaiser Permanente, 2022).

KITCHEN SAFETY AND SAFE FOOD HANDLING

Kitchens can harbor bacteria that may prove life threatening to a person with HIV/AIDS due to their compromised immune system. Separate dishes or eating utensils are not required, and dishes used by a person infected with HIV do not require special methods of cleaning. A person with HIV may prepare meals if they choose to, as the virus cannot be spread through food handling.

To avoid becoming infected by food-borne pathogens, foods that should not be eaten by the person with HIV include:

- Raw eggs or foods that contain raw eggs (e.g., homemade cookie dough, eggnog)

- Raw or undercooked poultry, meat, and seafood

- Unpasteurized milk or dairy products and fruit juices

It is important to wash hands, cooking utensils, and countertops often when preparing foods and to keep foods separate in order to prevent the spread of infectious agents from one food to another. A food thermometer is used to make certain foods are cooked to safe temperatures. Meat, poultry, eggs, seafood, or other foods likely to spoil within two hours of cooking or purchasing must be refrigerated or frozen (HIV.gov, 2021b).

CLOTHING AND OTHER LAUNDRY

Clothing and linens used by a person infected with HIV do not need to be separated from the rest of the household laundry. Clothes, washable uniforms, towels, or other laundry stained with blood/OPIM should be washed and disinfected before further use. If necessary, gloves are worn to remove or handle such items. Items are placed in the washing machine and soaked/washed first in cold, soapy water to remove any blood from the fabric. A second hot-water washing cycle and detergent will act as a disinfectant. Items are dried in a clothes dryer. Wool clothing or uniforms may be rinsed with cold, soapy water then dry cleaned to remove and disinfect the stain (Kaiser Permanente, 2022; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023).

TOILET AND BEDPAN SAFETY

It is safe to share toilets/toilet seats without special cleaning, unless the surface becomes contaminated with blood or OPIM. If this occurs, spray the surface with 1:10 bleach solution. Wearing gloves, wipe the seat dry with disposable paper towels.

Persons with open sores on their legs, thighs, or genitals should disinfect the toilet seat after each use. Urinals and bedpans should not be shared between family members unless these items are thoroughly disinfected after each person’s use (Kaiser Permanente, 2022; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023).

PERSONAL HYGIENE ITEMS

People should not share razors, toothbrushes, personal towels, washcloths, or other personal hygiene items. All items that are soiled with blood, semen, or vaginal fluid and are not flushable (such as paper towels, sanitary pads and tampons, and wound dressings) are placed in a plastic bag and securely closed before being placing in a trash container. The local health department can provide information on nearby disposal sites (Kaiser Permanente, 2022; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023).

HOUSEHOLD PETS

Household pets are not dangerous to people infected with HIV as long as the animals are healthy and have up-to-date immunizations. If the infected person cleans litter boxes, fish tanks, or birdcages, rubber gloves are worn and hands washed immediately following removal of gloves. All pet care is followed by thorough handwashing.

- Cats’ claws and dogs’ nails should be kept trimmed.

- Latex or nitrile gloves should be worn to clean up any pet urine, feces, vomit, or OPIM. The soiled area should be cleaned with a fresh 1:10 bleach solution.

- Pet food and water bowls should be washed regularly in warm, soapy water and rinsed clean.

- Cat litter boxes should be emptied out regularly and washed at least monthly.

- Fish tanks should be kept clean. Heavy latex gloves that reach to the upper arms, such as “calf-birthing” gloves, can be purchased from a veterinarian for immunocompromised individuals to wear to clean a fish tank.

- Pets should not be allowed to drink from the toilet or eat other animal feces, any type of dead animal, or garbage.

- Cats should be restricted to indoors. Dogs should be kept indoors or on a leash.

(Kaiser Permanente, 2022; St. Maarten AIDS Foundation, 2023)

PSYCHOSOCIAL AND MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

The stress associated with living with a serious illness or condition such as HIV can affect an individual’s mental health. People with HIV have a greater chance of developing mood, anxiety, and cognitive disorders. It has been shown that psychological issues are among the strongest links to the failure to adhere to HIV treatment. Therefore, psychosocial concerns should be assessed on a regular basis to identify stressors that may impact patient adherence to medical visits and medications (NIMH, 2022; MHA, 2023).

While identifying mental health issues among people living with HIV is critical, far too often these issues go undiagnosed and untreated. People may not want to reveal their psychological state to healthcare workers for fear of stigma and discrimination. Healthcare workers may not have the skills or training to detect psychological symptoms and may fail to take the necessary action for further assessment, management, and referral if symptoms are present (MHA, 2023).

Children and adolescents living with HIV may face an increased burden of mental and behavioral health disorders compared to adults. Challenges for this age group include accessing mental health services, mental health challenges during transition from pediatric to adult care services and responsibilities, and the impact of mental health intervention (AIDS2020, 2020).

Factors affecting mental health among this population can include:

- Pre-existing psychiatric conditions

- Personality vulnerabilities

- Affective disorders

- Addictions

- Responses to the social isolation and disenfranchisement associated with HIV diagnosis

- ART medication side effects

- Effects of HIV-related opportunistic infections

Situations that can contribute to mental health problems in people with HIV include:

- Difficulty telling others about an HIV diagnosis

- Stigma and discrimination associated with HIV

- Loss of social support and isolation

- Managing HIV medicines and medical treatment

- Dealing with loss, including the loss of relationships

- Difficulty in obtaining mental health services

(HIV.gov, 2021c)

Adjusting to the Diagnosis

Often, the first task for an HIV clinical care team is helping patients and family members cope with the psychosocial impact of the diagnosis. Being diagnosed with any chronic health condition can be extremely stressful, and it is normal to have an emotional reaction when given the diagnosis of HIV. However, when stress becomes prolonged and is not treated, more serious mental health conditions may develop.

Anger is a common and natural reaction to receiving the diagnosis of HIV. Many people are upset about how they contracted the virus or angry that they didn’t know they had the virus. These feelings and thoughts may be related to feelings of helplessness and being overwhelmed with the new diagnosis.

Other stressors that may arise when someone receives a diagnosis of HIV include having trouble getting the services needed, managing HIV medications, disclosing the HIV-positive diagnosis to others, losing contact with family or friends who fail to understand the realities of the disease, having to make lifestyle changes, and dealing with the stigma that has long been associated with HIV/AIDS (MHA, 2023).

With the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection is now manageable as a chronic disease in patients who have access to medication and who achieve durable virologic suppression, but mortality remains approximately five times higher in persons with HIV than the general population, and receiving a diagnosis of HIV means accepting the potential for a shorter lifespan (Rathbun, 2023).

Fear of Disclosing

At some point people living with HIV must decide whether and to whom to disclose their HIV status, which can be a difficult conversation. In Washington State, a partner must be notified either by the individual or by the public health department. Most people disclose their status to their spouse or partner within a short time following diagnosis, and this can strain the relationship. The negative effects may be mitigated by professional couples counseling (UW Medicine, 2023).

Partner notification can be provided through the local health department or some medical offices and clinics. Sometimes referred to as Partner Services, these providers contact and inform current and former partners that they may have been exposed to HIV and that the health department will provide them with testing, counseling, and referrals for other services that may be needed (CDC, 2021g).

Grief Issues

There are people who have experienced the loss of many friends from their social network as a result of AIDS, particularly in the earlier days of the epidemic, and grieving may become an ongoing experience. Today, with antiretroviral drugs, there is now a low rate of progression from HIV to AIDS, and people with HIV are no longer primarily dying of AIDS-defining illness.

Unacknowledged grief of same sex partners, lovers, and friends may be an issue if an individual’s relationship is not recognized as legitimate beyond a small circle of friends. Today in the United States, community attitudes have changed, and with society’s wider acceptance around sexual orientation, more education about HIV, and the legalization of same-sex marriage, this is gradually lessening (GriefLink, 2023).

Stigma and Discrimination

Although there have been significant improvements, there continues to be a risk that people who are infected with HIV will be more likely to feel stigmatized and isolated. Negative attitudes and beliefs about people with HIV may arise from labeling an individual as part of a group that is believed to be socially unacceptable. This may include beliefs that only certain groups of people can become infected by HIV and even moral judgments that people “deserve” to get HIV because of their choices.

Fearing that their diagnosis will result in the judgmental behaviors of others, rejection, or abandonment, many may hide the true cause of their illness, informing only a few of their family and friends, and sometimes informing no one. This isolation and lack of support increases their emotional and spiritual pain. Social stigmas associated with HIV have been identified as a possible contributor to the increased suicide rate in people infected with HIV.

HIV-related stigma is often connected with other sources of stigma, including those associated with mental health and/or substance use disorders. For HIV-infected persons with comorbid mental health disorders, there is a double burden of stigma. Internalized stigma (self-stigma) is as damaging to the mental well-being of people with HIV as stigma from others. Negative self-judgment results in shame, feelings of worthlessness, and blame, all of which affect the person’s ability to live positively and limit qualify of life (GriefLink, 2023; AIDS2020, 2020; CDC, 2021g).

Neuropsychiatric Effects of HIV/AIDS

The term neuropsychiatric encompasses a broad range of medical conditions that involve both neurology and psychiatry. There is a high prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders among those infected with HIV, and studies have shown that patients with neuropsychiatric conditions have poorer outcomes and benefit less from antiretroviral therapy. Psychiatric treatment, however, does improve outcomes.

HIV itself increases the risk of neuropsychiatric conditions because it causes major inflammation within the body. The entire brain, including the lining, becomes inflamed as a result of the body’s immune response, causing irritation and swelling of brain tissue and/or blood vessels, resulting in nontraumatic brain damage over the long term. Having brain damage such as this is a known risk factor for the development of a neuropsychiatric condition.

Because HIV affects the immune system, the person also has an increased risk for other infections that can affect the brain and nervous system and lead to changes in behavior and functioning.

Starting antiretroviral therapy can also affect a person’s mental health in different ways. Some antiretroviral medications have been known to cause symptoms of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance and may make some mental health conditions worse (MHA, 2023; Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

The availability of effective psychiatric care for HIV-infected patients is crucial for their treatment and also for controlling the spread of HIV. Neuropsychiatric care in HIV disease ranges from management of clinical presentations of other psychiatric disorders, supportive psychotherapy, and treatment of specific conditions such as HIV-associated dementia, minor cognitive motor disorder, and AIDS mania. The availability of effective psychiatric care for HIV-infected patients is crucial for their treatment and also for controlling the spread of HIV.

DEPRESSION

Clinical depression is the most commonly known and reported psychiatric disorder among those with HIV, affecting 22% of the population. HIV increases the risk of developing depression through direct damage to subcortical brain areas, chronic stress, worsening social isolation, and intense demoralization. Patients with symptomatic HIV disease are significantly more likely to experience a major depressive episode than those with asymptomatic disease.

Critical “crisis points” are common entry points for the development of depression in HIV-infected people and can include:

- Initial HIV diagnosis

- Disclosing HIV status

- Introduction of new medications

- Recognition of new symptoms and disease progression awareness

- Hospitalization

- Physical illness

- Death of a significant other

- AIDS diagnosis

- Returning to work, going back to school

- Major life events such as relocation, change of jobs, loss of a job, pregnancy or giving birth, end of a relationship

- Making end-of-life and permanent planning decisions

(Lieber, 2021)

A patient with depression may present with the following symptoms:

- Depressed mood

- Loss of pleasure from activities

- Anorexia

- Morning insomnia or hypersomnia

- Difficulty concentrating

- Thoughts of suicide

(Lieber, 2021)

Depression is common among women with HIV and may be a contributing factor to negative outcomes in this population. A dose-related association has been found between cumulative days with depression and mortality in women; each additional 365 days of depressive symptoms were found to be associated with a 72% increase in mortality risk. Depression is an important factor in adhering to ART, with a high probability that patients with depression are more likely to not stay actively engaged in care (Aberg & Cespedes, 2023).

Evidence has shown that depression is also highly prevalent among adolescents living with HIV when compared to those without. Factors may include:

- Severity of HIV infection

- Stages of the disease

- Presence of opportunistic infection

- Presence of other mental health problems

- Presence of addition psychosocial stress or trauma

(Ayano et al., 2021)

ANXIETY

It is estimated that up to 38% of people with HIV will develop an anxiety disorder. Symptoms are twice as common in women as in men and can be prominent when patients are diagnosed with HIV and in response to progression of the illness.

Common symptoms of anxiety include:

- Excessive worry

- Feeling “on edge”

- Difficulty concentrating

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Muscle and/or jaw tension

- Changes in appetite

- Changes in libido

- Increased use of drugs or alcohol

- Tachycardia

- Sweating and flushing

- Panic attacks

(THT, 2023)

POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER (PTSD)

There is a complex relationship between PTSD and HIV infection. PTSD exacerbates HIV risk behaviors and worsens health outcomes, while HIV risk behaviors, such as prostitution and drug abuse, can result in increased exposure to trauma associated with the increased likelihood of developing PTSD. PTSD from early trauma predisposes individuals to engage in sex or drug behaviors, which then increases risk of HIV infection.

PTSD often coexists with depression and cocaine/opioid abuse, both of which are risk factors for HIV. Substance use may be either a strategy to obtain relief in response to a traumatic experience or a lifestyle that increases exposure to traumatic events such as robbery or assault (Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

AIDS MANIA

AIDS mania is associated with late-stage HIV infection and is characterized by typical mania and additional cognitive impairment in the setting of a lack of previous personal or family history of bipolar illness. The prevalence of AIDS mania has dropped significantly since the onset of potent antiretroviral therapy.

AIDS mania involves less euphoria and more irritability than mania associated with bipolar illness and is also much more chronic. In contrast to bipolar mania, AIDS mania usually does not remit if left untreated (Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

HIV-ASSOCIATED NEUROCOGNITIVE DISORDERS (HAND)

Changes in attention, memory, concentration, and motor skills are common among HIV-infected individuals. When such changes are clearly attributable to HIV infection, they are classified as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Depending on the severity and impact on daily functioning, cognitive deficits can be further classified into three conditions:

- Asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment (ANI)

- HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder (MND)

- HIV-associated dementia (HAD)

The widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy has been associated with a decrease in the prevalence of more severe neurocognitive deficit, such as HAD, but milder cognitive deficits without alternative explanation remain common, even among patients with viral suppression.

HAND is characterized by the subacute onset of cognitive deficits, central motor abnormalities, and behavioral changes. Risk factors for HAND include a low nadir CD4 cell count, age, and other comorbidities, such as cardiovascular and metabolic disease.

The main cognitive deficits that have been reported in milder presentations of HAND include problems with attention and working memory, executive functioning, and speed of informational processing. The onset and course are generally more slow-moving, and deficits may remain stable or apparently unchanged for years.

HAD is related to the effect of HIV on subcortical and deep grey matter structures and occurs mainly in patients who are untreated with advanced HIV infection. Unlike other neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease), deficits occurring in HAD may come and go over time. Onset of impairment is most often subacute, and cerebral atrophy is often evidenced on brain imaging.

Risk factors for HAD include high serum or cerebrospinal fluid HIV viral load, low education level, advanced age, anemia, illicit drug use, and female gender. The dementia is characterized by subcortical dysfunction with:

- Attention-concentration impairment

- Depressive symptoms

- Impaired psychomotor speed and precision

Patients with HAD may also have changes in mood that can progress to psychosis with paranoid ideation and hallucinations, and some may develop mania (Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

DELIRIUM

Because of the complexity and the number of comorbid disorders, delirium is highly prevalent in those with HIV disease. Differential diagnosis includes:

- HIV-associated dementia

- AIDS mania

- Minor cognitive motor disorder

- Major depression

- Bipolar disorder

- Panic disorder

- Schizophrenia

Delirium can usually be distinguished by its rapid onset, fluctuating level of consciousness, and a link to a medical etiology (Pieper & Teisman, 2023).

Mental Health Interventions

Mental health problems associated with HIV/AIDS are often neglected. Their presence compromises HIV care and prevention efforts, and when unaddressed, they compromise treatment outcomes, increase HIV virus-resistant strains, leave pockets of potential HIV spread in the community, and can lead to a poorer quality of life and early death of persons living with HIV/AIDS. Integrating behavioral health services along with HIV care holds promise for improving substance use, mental health, and HIV-related health outcomes.

The goal of mental health management is to assist the patient living with HIV to manage symptoms and live as well as possible. Effective treatment plans usually involve a combination of medication, therapy, and social support. Healthcare providers can refer HIV patients for mental health management to a mental health provider for care, which may include:

- Psychiatrists, who treat mental health problems with various therapies and prescribe medications such as antidepressants, anti-anxiety medication, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizing drugs

- Psychologists and other therapists, who treat mental health problems with various therapies, such as regular talk therapy in individual, group, marital, or family settings, and behavioral interventions, such as yoga, meditation, mindfulness, symptom management strategies, and education

- Mental health or social support groups, which include organized groups of peers who meet to provide mental health support to one another either in person, through online forums, or via HIV/AIDS hotlines

(HIV.gov, 2022e; Musisi & Nakasujja, 2022)

Issues for Families and Caregivers

The psychological suffering and grief experienced by people with HIV/AIDS is also shared by family members, friends, caregivers, and partners. Partners and families are often the people who provide most of the physical and emotional care for individuals with chronic illness, including HIV. This can be very stressful and lead to tension among members of the family.

A variety of issues may arise when a family member has been diagnosed with HIV, such as:

- The diagnosis may reveal behaviors that the person may have wanted to keep private. These might include sexual behaviors or intravenous drug use, which can result in feelings of guilt or blame and can lead to a relationship breakdown.

- More than one person in a family may be unwell, adding to the burden of care, causing additional emotional and financial problems.

- Fear of stigma and discrimination may mean that the diagnosis is kept secret. This can prevent immediate family members from accessing the wider support of extended family members or the community.

- A family with a child who is infected with HIV must consider when and how to disclose this information to the child.

- Parents may find it problematic to discuss sexual behavior and risk with younger children, which can have prevention implications for them later on.

- When a child with HIV reaches adolescence, problems can arise concerning adherence to treatment and safe sexual behavior.

- Poor access to information can result in people not taking their medication as prescribed or not attending healthcare visits regularly. Members of the family may disagree about the best course of treatment.

- Family members may have to cope with the mental health problems that commonly develop in people who are living with HIV.

(AAMFT, 2023)

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CAREGIVER SELF-CARE

- Seek support from other caregivers.

- Become educated about HIV, ART, and comorbidities.

- Take care of your own health so you are strong enough to take care of your loved one.

- Accept offers of help and suggest specific things people can do to help you.

- Learn how to communicate effectively with healthcare providers.

- Take respite breaks often.

- Be watchful for signs of depression and get professional help when needed.

- Be aware and open to new technologies that can help caregiving efforts.

- Organize medical information so that it is up to date and easy to locate.

- Make certain that legal documents are in order.

(NFCA, 2023)

End-of-Life Issues

Because of the advancement of effective antiretroviral therapy, the increased life expectancy for persons diagnosed with HIV is contributing to a rapidly aging HIV-infected population with a high prevalence of comorbidities. These comorbidities, and not HIV, are most often the cause of death for people in this population.

For patients with HIV/AIDS who are approaching the end of life, creating advance directives that outline their choices and preferences for care can be difficult. One of the most important decisions is whether and when to discontinue ART. This is particularly stressful for both the patient and family because it may be seen as “giving up.”

Individuals who are dying from a condition besides AIDS must consider whether or not to continue to receive antiretroviral treatment. Reasons for continuing ART may include:

- Discontinuance will lead to uncontrolled viremia, which could contribute to symptom burden.

- ART may help sustain cognitive functioning, as system viral load does not always correlate with central nervous system viral load.

Reasons for considering discontinuation of ART may include:

- Continuing medications might contribute to anxiety for patients who have trouble taking medication, cause confusion about goals, and distract from advanced care planning.

- Patients may experience “pill burden” and potential drug-drug interactions with common palliative care medication. For example, some ART medications increase levels of some opioids (e.g., oxycodone) while decreasing the levels of other opioids (e.g., methadone).

With continued treatment, the patient may choose palliative care. If treatment for HIV is to be discontinued, the choice for hospice care during the last six months of life recognizes that treatment is no longer of benefit and the disease will run its course (Pahuja et al., 2023).

Issues Affecting Special Populations

HIV/AIDS takes a heavy toll on people of all ethnicities, genders, ages, and income levels. However, some populations have been uniquely affected by the epidemic.

SEXUAL MINORITIES

The high prevalence of mental health problems among sexual minorities has been attributed to sexual minority stress. Minority stress may contribute to identity conflict and increase condomless anal sex by isolating men who have sex with men, transgender women, and gender nonbinary people of color (Sarno et al., 2022).

PEOPLE WHO INJECT DRUGS

People with HIV who use injection drugs are a population with extensive psychiatric, psychological, and medical comorbidities, the most significant being major depression. Depression is associated with worsening of addictions and resistance to treatment. Patients who are depressed often find it difficult to engage in, invest in, and sustain treatment.

Because drug use is criminalized, people who use drugs often live or take drugs in underground, hidden places, making it harder for services to reach them. Healthcare workers, police, and other law enforcement agents are often discriminatory toward people who use drugs, which prevents them from wanting to access HIV services (Be in the KNOW, 2023b).

ADOLESCENTS WITH PERINATAL HIV INFECTION

The prevalence of mental health disorders in youth with perinatally acquired HIV is high, with nearly 70% meeting the criteria for a psychiatric disorder at some point in their lives. The most common conditions include anxiety and behavioral disorders, mood disorders (including depression), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, all of which complicate adherence to treatment and retention in care. The prevalence of attempted suicide is also notably higher in adolescents with HIV compared to others.

Adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV are also at risk for neurocognitive impairment and substance use disorders, which also can interfere with medication adherence.

Challenges that affect the treatment of adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV include extensive drug resistance, complex regimens, the long-term consequences of HIV and antiretroviral exposure, the developmental transition to adulthood, and psychosocial factors.

Assessment of antiretroviral adherence in adolescents with HIV can be challenging, with discordance between self-report and other adherence measures, such as viral load and therapeutic or cumulative drug levels. This should involve immediate and open discussions with the adolescent and their caregiver(s) (HIV.gov, 2023e).

LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES

Legal standards are set forth in the form of written laws passed by governments. Ethical considerations are based on the principles of right and wrong and guide how laws can be obeyed. These issues include criminalization laws, confidentiality and anonymity, informed consent, criminalization laws, disability and discrimination, and HIV reporting requirements.

Criminalization Laws

As of 2022, 35 states have laws that criminalize HIV exposure. The CDC has grouped such laws into four categories:

- HIV-specific laws that criminalize or control actions that can potentially expose another person to HIV

- Sexually transmitted disease (STD), communicable, contagious, infectious disease laws that criminalize or control actions that can potentially expose another person to STDs/communicable/infectious disease (which might include HIV)

- Sentence enhancement laws specific to HIV or STDs that do not criminalize a behavior but increase the sentence length when a person with HIV commits certain crimes

- No specific criminalization laws

(CDC, 2023g)

At least 12 states, including Washington, have modernized or repealed their HIV criminal laws. Changes include moving HIV prevention issues from the criminal code to disease control regulations; requiring intent to transmit and actual HIV transmission; and providing defenses for taking measures to prevent transmission, including viral suppression or being noninfectious, condom use, and partner pre-exposure prophylaxis use (CDC, 2023g).

Washington State criminalization law RCW 9A.36.011 states, “A person is guilty of assault in the first degree if he or she, with intent to inflict great bodily harm, transmits HIV to a child or vulnerable adult,” which is a class A felony (WSL, 2020b).

Confidentiality

Some states have laws that protect a person’s right to anonymous testing for HIV in particular. Under these laws, a person may get tested for HIV without their name or other personally identifying information being attached to the result.

Confidential testing differs from anonymous testing and is not truly anonymous. The person’s name and other identifying information is attached to the test results and entered into the person’s medical record, which can be viewed by both doctors and health insurance companies. A confidential test released to the state or local health department will have the person’s name attached, and the state department then removes the identifying information and sends the results to the CDC for the purposes of national HIV estimates (Johnson, 2022).

Washington State law prohibits disclosure of a HIV test result without the specific written consent of the person to whom it pertains, or as otherwise permitted by state law. A general authorization for the release of medical or other information is not sufficient for this purpose. Permitted recipients of HIV test results are limited to:

- The subject of the test

- A person with a “release of information” from the tested person

- Health officials, in accordance with reporting requirements for diagnosed sexually transmitted disease

- Facilities that collect blood, tissue, or semen

- Health officials, first responders, or victims of sexual assault who petition the court to order testing

- A person allowed access to information by a court order

- Local law enforcement if health officers have exhausted procedures to stop behaviors that present a danger to public health

- Exposed persons who are notified because releasing the identity of the infected person is necessary

- Payers of health claims