Dementia: Alzheimer's Disease Patient Care

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

Alzheimer's disease and dementia continuing education course. Covers pharmacologic and medical therapies, the role of rehabilitation in caring for patients with Alzheimer's, strategies for addressing the effects of AD, and ways to support families and caregivers. Earn 10 contact hours with this Alzheimer's CEU. Newly updated bestseller course!

Course Price: $49.00

Contact Hours: 10

Case Management Contact Hours: 7.25

Pharmacotherapeutic Hours: 0.5

Course updated on

January 14, 2025

"Great Course! I am a Geriatric Nurse Specialist and thought I knew all there was to know about Alzheimers, but I learned so much more with this course!" - Laura Bryant, RN

"Very comprehensve with sound practical application based on evidence-based practice." - Lisa, RN in California

"Excellent course. I also work closely with clients with Alzheimer's disease and their families, and I recently lost an uncle to Alzheimer's. Very Helpful!" - Tina, RN in West Virginia

"Great course! Liked the brain images provided. Comprehensive!" - Siobhan, OT in North Carolina

Dementia: Alzheimer’s Disease Patient Care

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will have increased your knowledge of evidence-based guidelines for delivering appropriate therapeutic interventions to persons with Alzheimer’s disease, their family members, and caregivers. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Summarize the epidemiologic and societal impacts of Alzheimer’s disease.

- List risk factors and possible preventive measures for Alzheimer’s disease.

- Identify the signs, symptoms, and diagnostic steps for the disease.

- Discuss available pharmacologic and medical therapies.

- Summarize strategies in the rehabilitation and care of persons with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Identify interventions in managing problem behaviors.

- Describe effective support for families and caregivers.

- Discuss ethical, legal, and end-of-life considerations.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Scope of the Disease

- What Is Alzheimer’s Disease?

- Alzheimer’s Disease Signs and Symptoms

- Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease

- Pharmacologic and Medical Management

- Rehabilitation for Persons with Dementia

- Supportive Care for the Person with Alzheimer’s Disease

- Learning to Manage Problem Behaviors

- Caring for the Caregivers

- Ethical and End-of-Life Considerations

- Conclusion

- Resources

- References

INTRODUCTION

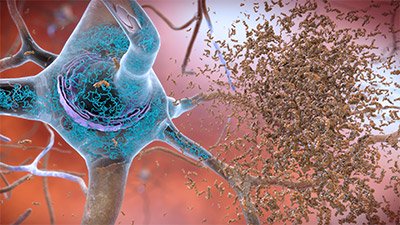

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, who in 1906 noticed changes in the brain tissue of a woman who had died of an unusual mental illness. Her symptoms included memory loss, language problems, and unpredictable behavior. Following her death, he examined her brain and found many abnormal clumps (amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibers (neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles).

These plaques and tau tangles in the brain are some of the main physical features of AD. Another feature is the loss of connections between neurons that transmit messages between different parts of the brain and from the brain to muscles and organs of the body (NIA, 2023a).

Alzheimer’s disease is one of a group of disorders called dementias, which are brain failures characterized by progressive cognitive and behavioral changes. The most common forms of dementia are:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Vascular dementia

- Multi-infarct dementia

- Subcortical vascular dementia

- Stroke-related dementia

- Frontotemporal dementia (Pick’s disease)

- Mixed dementia (a combination of two or more types)

Other rarer conditions that can result in dementia include:

- Atypical Alzheimer’s disease

- Cadasil (a rare inherited form of vascular disease)

- Corticobasal syndrome (CBS)

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)

- HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND)

- Huntington’s disease

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH)

- Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

(Alzheimer’s Society, 2024a)

Alzheimer’s disease results from a complex pattern of abnormal changes, develops slowly, and gradually worsens. The course of Alzheimer’s and the rate of decline vary from person to person. Alzheimer’s disease can be present for many years before there are clinical signs and symptoms of the disease. On average, a person with Alzheimer’s lives for four to eight years after diagnosis. However, some may live for as many as 20 years.

Alzheimer’s disease is reported as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. However, studies have found that it is underreported as an underlying cause of death. It is the only cause among the top 10 that cannot be prevented or cured. However, currently some treatments can help manage symptoms and slow disease progression for a period of time (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024a).

Historical Perspective

“Senile dementia”—the loss of memory and other intellectual faculties that occurs in older adults—was recognized in the time of Hippocrates. In the centuries that followed, this condition was thought to be simply a result of old age, commonly called hardening of the arteries. Diseases of old age, however, were considered unimportant until the second half of the 19th century. Prior to this period, people in the United States lived an average of 50 years and few reached the age of greatest risk for Alzheimer’s disease. For this reason, the disease was considered rare, and there was little scientific interest in it.

This changed as the average lifespan increased and Alzheimer’s became more common in people aged 70 and older. During this period of time, advancements in medicine and the ability to look inside the brain gave the medical community the realization that diseases could be the cause of this deterioration.

| (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024b) | |

| 1906 | German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer first described the pathology of the disease after using staining techniques to identify amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain associated with the symptoms of senile dementia. |

| 1910 | The disease was labeled Alzheimer’s disease by Emil Kraepelin. |

| 1931 | After the invention of the electron microscope, it became possible to conduct further study of the brain by viewing actual brain cells, opening the door to research into many areas of brain disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease. |

| 1968 | The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale was developed to measure cognitive function at baseline and to identify improvement or deterioration over time. |

| 1976 | Alzheimer’s disease was recognized as the most common form of dementia. |

| 1980 | The Alzheimer’s Association was founded. |

| 1983 | National Alzheimer’s Disease Month was declared. |

| 1984 | Beta-amyloid was identified as forming Alzheimer’s disease’s characteristic plaques, which cause reduced neurologic function. A nationwide infrastructure for Alzheimer’s research was established by the National Institute on Aging. |

| 1986 | Tau protein was identified as forming Alzheimer’s disease’s characteristic neurofibrillary tangles. |

| 1987 | The first Alzheimer’s drug trial (tacrine) was begun. The first deterministic Alzheimer’s gene, amyloid precursor protein (APP), was discovered. |

| 1993 | The first Alzheimer’s disease risk factor gene was identified, called APOE4. The first Alzheimer’s drug, tacrine (Cognex), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). |

| 1994 | President Reagan announced he had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The first World Alzheimer’s Day was held. |

| 1996 | FDA approved donepezil (Aricept), a cholinesterase inhibitor, for treating Alzheimer’s-type dementia. |

| 1999 | Report published showing that injecting transgenic “Alzheimer’s” mice with beta-amyloid prevents the animals from developing plaques and other Alzheimer’s-like brain changes. |

| 2000 | FDA approved rivastigmine (Exelon), a cholinesterase inhibitor, for treating all stages of Alzheimer’s disease. |

| 2001 | FDA approved galantamine (Razadyne), a cholinesterase inhibitor, for treating mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. |

| 2003 | FDA approved memantine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist that reduces certain types of brain activity by binding to NMDA receptors and blocking the activity of glutamate, which in Alzheimer’s disease can overstimulate nerve cells and kill them. |

| 2004 | A new imaging agent known as Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) was produced to be used with positron emission tomography for early detection of Alzheimer’s. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative was begun to share research data worldwide. |

| 2009 | An effort was begun to standardized biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. |

| 2011 | Alzheimer’s disease advanced to become the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and the fifth leading cause of death for persons over the age of 65. Canadian scientists used a technique known as deep brain stimulation (applying electricity to regions of the brain) to reverse Alzheimer’s disease-related memory loss. Annual assessment for cognitive impairment for all Medicare recipients was implemented as part of an annual wellness visit. President Obama signed the National Alzheimer’s Project Act into law, a framework for a national strategic plan. |

| 2012 | Scientists at University College London discovered that specific antibodies that block the function of a related protein (Dkk1) are able to completely suppress the toxic effect of beta-amyloid on synapses. The first major clinical trial for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease was begun. |

| 2013 | International Genomics of Alzheimer’s Project researchers identified new genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. |

| 2014 | FDA approved donepezil combined with memantine (Namzaric) for treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Rates of death caused by Alzheimer’s disease were found to be much higher than reported on death certificates. |

| 2015 | A UCLA study identified three distinct subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease: inflammatory, noninflammatory, and cortical (associated with significant zinc deficiency). Research began to determine if they have different underlying causes and respond differentially to potential treatments. |

| 2017 | An historic $400 million increase for federal Alzheimer’s disease research funding was signed into law, bringing annual funding to $1.4 billion. |

| 2018 | Dementia Care Practice Recommendations were developed to help professional care providers deliver optimal quality, person-centered care. |

| 2021 | Aducanumab (Aduhelm), the first therapy to address the underlying biology of Alzheimer’s disease, received accelerated approval by the FDA for limited use. |

| 2023 | Lecanemab (Leqembi), which addresses the underlying biology of AD, was approved for treatment of early AD. Donanemab (Kisunla) was approved; it removes beta-amyloid from the brain. |

| 2024 | Aducanumab (Aduhelm) was discontinued by its manufacturer, Biogen. |

Scientists continue the search for answers regarding causes, diagnoses, and treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, but developing new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease has proven difficult. Some challenges in developing new treatments include:

- Most drugs fail during testing.

- Brains are almost impenetrable and are protected by the blood-brain barrier.

- Treating a symptom isn’t treating a disease.

- There is inadequate funding for Alzheimer’s research.

- Scientists aren’t sure what causes Alzheimer’s disease.

(Brookshire, 2024)

SCOPE OF THE DISEASE

Alzheimer’s Disease Worldwide

Every three seconds someone in the world develops dementia, and every year there are nearly 10 million new cases. Worldwide, more than 55 million people are living with Alzheimer’s and other dementias, over 60% of whom are in low- and middle-income countries. That number is expected to increase in 2030 to 78 million and in 2050 to 139 million. Dementia is one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people globally. Dementia is currently the seventh leading cause of death, and 65% of dementia-related deaths are in women (WHO, 2024).

A systematic review and meta-analysis done in 2020 showed that the prevalence of dementia was higher in Europe and North America than in South America, Asia, and Africa. China has surpassed all other countries to become the nation with the highest number of dementia patients. Currently more than 15 million people ages 60 and above in China have dementia, accounting for a quarter of all dementia patients worldwide. Of this number, 9.83 million have Alzheimer’s disease. The disease is now affecting people in China at a younger age, with 21.4% being below the age of 60. AD and other dementias have become an increasingly serious public and social problem (Lv et al., 2023; Global Times, 2023).

A recent study reveals that two small Indigenous groups in the Bolivian Amazon have among the lowest rates of dementia in the world, at around 1% in people ages 60 and older (Miller, 2022).

Alzheimer’s Disease in the United States

It is estimated that as many as 6.9 million Americans age 65 and older have Alzheimer’s disease. As the size of the U.S. population ages 65 and older continues to grow, so too will the number and proportion of Americans with AD and other dementias. By 2050, the number of people age 65 and older with Alzheimer’s may reach a projected 12.7 million unless there is a medical breakthrough to prevent or cure the disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024a).

The states with the highest prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease are in the east and southeast regions, with the highest in Maryland (12.9%), New York (12.7%), and Mississippi (12.5%). States with the highest number of people with AD were California, Florida, and Texas. Among larger counties, those with the highest prevalence of AD were Miami-Dade County in Florida, Baltimore City in Maryland, and Bronx County in New York (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024c).

BY AGE

Following is the distribution of Alzheimer’s by age in the United States:

- 65–74 years: 26.4%

- 75–84 years: 38.6%

- 85+ years: 35.4%

(Statista, 2024a)

BY SEX

Almost two thirds of Americans with AD are women. Of the 6.9 million people ages 65 and older with AD, 4.2 million are women (11%) and 2.7 million (9%) are men. The main reason for this is that women live longer than men and older age is the biggest risk factor for this disease. Studies have been unclear whether those of female sex are more likely to develop dementia than those of male sex (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024a). (See also “Sex” under “Etiology and Risk Factors of Alzheimer’s Disease” later in this course.)

BY RACE/ETHNICITY

African Americans are about two times more likely than White people to have Alzheimer’s and other dementias but only 34% more likely to have a diagnosis. They are also more likely to be diagnosed in later stages. Hispanics are about one and one half times more likely than White people to have Alzheimer’s and other dementias but only 18% more likely to have a diagnosis (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024d).

As many as 1 in 3 Native American older adults will develop Alzheimer’s or some other form of dementia. Between 2020 and 2060, the number of American Indian/Alaska Native individuals age 65 and older living with dementia is projected to increase fourfold. More than one third of Native Americans say they do not expect to live long enough to develop Alzheimer’s, and more than half (53%) believe that significant memory or cognitive losses are a normal part of aging (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024e).

BY EDUCATION LEVEL

Research has found a high educational level to be associated with a 30% lower risk of Alzheimer’s compared with a low educational level. Combining genetic risk and education categories, individuals with a low genetic risk and a high educational level had a more than 90% lower risk of AD compared to those with a high genetic risk and low educational level (Li et al., 2023).

MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY

Before a person with Alzheimer’s dies, they live through years of morbidity as the disease progresses.

Between 2019 and 2020, the total number of deaths from Alzheimer’s disease increased 10.5%, with COVID-19 being a significant contributor. In 2022, AD was the seventh-leading cause of death in the United States, with more than 120,000 deaths and an age-adjusted mortality rate of 28.9 per 100,000 people. This was a nearly 7% decline from 2021, when deaths from AD had more than doubled between 2000 and that year. Among Americans ages 65 and older, AD is the fifth-leading cause of death (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023a).

Alzheimer’s disease is associated with excess comorbidity, including hypertension, diabetes (types 1 and 2), cardiovascular disease, and depression. There is evidence that risk factors common to comorbidities and AD, such as chronic inflammation, can place individuals with comorbidities at increased risk of developing AD. The interplay between comorbidities and development and progression of AD, however, remains incompletely understood (Lanctôt et al., 2023).

UNDERDIAGNOSIS OF ALZHEIMER’S

A 2019 study indicated that Alzheimer disease may be an underlying cause of five to six times as many deaths as currently reported. This is due to the fact that prevalence studies are designed so everyone in the study undergoes evaluation for dementia. Outside of research settings, however, a substantial portion of those who would meet the diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s and other dementias are not diagnosed by a physician. As result, a large portion of those with dementia may not know they have it.

Almost all existing Alzheimer’s prevalence studies are based on identification of clinical symptoms and do not rely on the brain changes believed to be responsible for the disease. Both autopsy studies and clinical trials have found that 15%–30% of those who meet the criteria based on symptoms did not have Alzheimer’s-related brain changes. Therefore, estimates could be up to 30% lower than estimates based only on symptoms (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024a).

Financial Impact of Alzheimer’s

Medical and long-term care for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias impose a large economic burden on both individuals and societies. Nationally, in 2022 the estimated healthcare costs associated with Alzheimer’s disease treatment were $321 billion, with costs projected to exceed $1 trillion by 2050. Medicare and Medicaid cover approximately two thirds of these costs. The remaining costs, including out-of-pocket expenditures, are typically borne by the patients and their families, private insurance, health-maintenance or managed-care organizations, and uncompensated care.

The total lifetime cost of care for a patient with dementia was estimated at $412,936 in 2022 dollars, with 70% of those costs borne by family caregivers in the form of unpaid caregiving and out-of-pocket expenses for items ranging from home health support to medications. An estimated 11.3 million family and unpaid caregivers of individuals with AD or other dementias provided approximately 16 billion hours of informal (unpaid) assistance valued at approximately $271.6 billion.

The average total annual costs for Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older with AD or other dementias have been estimated to be $41,757, which is about three times higher than for those without dementia. The average Medicaid costs for Medicare beneficiaries with AD have been found to be 22 times higher than for those without AD ($64,478 vs $291).

In 2021, nursing home care averaged $95,000 to $108,405 per year, and formal home care cost was around $27 per hour, or roughly $56,160 annually for 40 hours of in-home care per week. In 2000, home health care expenditures amounted to $32 billion. By 2022, however, this figure had increased to $133 billion (Skaria, 2022).

The most expensive long-term care service in the United States is a nursing home, where the annual cost for a semiprivate room was $104,025 in 2023. With an annual cost of $54,200, a single bedroom in an assisted living facility was cheaper than a nursing home and varied by state.

The average cost of informal care for patients with dementia is more than double the corresponding cost of care for patients without dementia, $83,022 versus $38,272.

As the population ages and families are less able to bear the cost of long-term care, the current system may be unable to meet the growing demand without alternative care programs and sustainable financing (Statista, 2024b).

WHAT IS ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE?

Normal aging involves changes throughout the body, and the brain is not exempt. In normal aging, the volume of the brain decreases each year after age 65, with greatest loss in the frontal and temporal lobes and greater loss of white matter than gray matter in cognitively normal older adults. Cerebral blood flow decreases up to 5%–20%, with deterioration of mechanisms that maintain cerebral blood flow with fluctuation in blood pressure.

Age-related neuronal loss is most prominent in the largest neurons in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex. The hypothalamus, pons, and medulla have modest if any neuron or volume losses with normal aging. Age-related neuron loss is likely due to programmed cell death (apoptosis) rather than inflammation, ischemia, or other mechanisms.

Age also affects neurons that persist, with loss of dendritic tree, shrinkage of processes, and decrease of synapses. Such changes may contribute more to age-related loss of brain volume than the loss of neurons. In some areas, dendritic connections may increase, which may be due to repatterning of the brain invoked to compensate for cellular death. Neurons continue to form new synapses, and new neurons are formed throughout the lifespan, but rates of loss are greater than gains.

Lipofuscin accumulates in certain areas of the brain, particularly the hippocampus and frontal cortex, both of which are associated with memory formation, but the impact of lipofuscin on function is unknown.

Neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques, which are two characteristic lesions of Alzheimer’s disease, occur in certain areas of the brain in normal aging but to a lesser extent than in Alzheimer’s disease. More than 50% of cognitively normal individuals over age 85 have sufficient plaques/tangle burden to make a pathologic diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (Taffet, 2023).

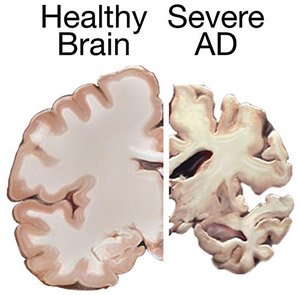

Shrinkage of the brain due to Alzheimer’s disease. (Source: National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health.)

Pathophysiology

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by two abnormalities in the brain: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Neurofibrillary tangles are bundles of twisted filaments found within neurons. These tangles are largely made up of a protein called tau. Amyloid plaques, which are found in the tissue between the nerve cells, are unusual clumps of a protein called beta-amyloid and degenerating bits of neurons and other cells (Stanford Medicine, 2024a).

Neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid plaques. (Source: National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health.)

These pathologic changes are accompanied by a loss of neurons, particularly cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and the cortex. Two prominent pathophysiological hypotheses have been proposed based on these pathological findings.

- The cholinergic hypothesis proposes that the reduced levels of acetylcholine in the brain resulting from neuronal loss play a significant role in AD development. This hypothesis stems from the early loss of cholinergic neurons in AD. Beta-amyloid (also called amyloid beta) is believed to negatively affect cholinergic function by causing cholinergic synaptic loss and impaired acetylcholine release. Anticholinergics also adversely affect memory in older patients clinically.

- The amyloid hypothesis is currently the most widely accepted pathophysiologic mechanism for AD, especially in cases of inherited AD. The amyloid hypothesis suggests that amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide is derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP) through the actions of beta- and gamma-secretase enzymes. Usually, APP is split by either alpha- or beta-secretase, and the tiny fragments formed by them are not toxic to neurons—however, sequential splitting by beta- and then gamma-secretase results in 42-amino-acid peptides (Aβ42). Elevation in levels of Aβ42 leads to aggregation of amyloid that causes neuronal toxicity.

(Kumar et al., 2024)

A 2023 study indicates an additional hypothesis that a form of cell death known as ferroptosis (caused by a buildup of iron in the cells) destroys microglia cells (involved in the brain’s immune response) in cases of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. The researchers discovered that microglia degenerate in the white matter of the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, and the cascading effect of this degeneration appears to be a mechanism in advancing cognitive decline. The underlying cause of the cycle of decline is likely related to repeated episodes of low blood flow and oxygen delivery to the brain over time due to acute stroke or chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes (Robinson, 2023).

Other theories include:

- Tau propagation hypothesis

- Inflammation hypothesis

- Oxidative stress hypothesis

- Mitochondrial hypothesis

- Infectious hypothesis

- Calcium hypostasis hypothesis

- Metal ion hypothesis

- Ion channel cell hypothesis

- Autoimmune hypothesis

- Epigenetic hypothesis

(Mehta & Mehta, 2023)

Etiology and Risk Factors of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s is a complex disease with no single, clear-cut etiology and therefore no sure means of prevention or “silver bullet” cure or treatment. Scientists understand that for most people Alzheimer’s is an ecologic disease caused by genetics and the interaction of genes with other internal and external factors over many years, leading to changes in brain structure and function. This means that genetics plays an important role, together with how genes are affected by external factors such as environment and lifestyle (epigenetics), some of which are modifiable and some of which are not.

GENETIC RISK FACTORS

Variations in genes—even small changes—can affect the likelihood of a person developing Alzheimer’s. In most cases, AD does not have a single genetic cause. Instead, it can be influenced by multiple genes in combination with lifestyle and environmental factors. A person may carry more than one genetic variant or group of variants that can either increase or reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s.

People who develop AD do not always have a history of the disease in their families. Those with a parent or sibling with the disease, however, have a higher risk of developing it than those who do not have a close relative with the disease.

Genes Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease

Genetic variants that affect AD risk include the apolipoprotein (APOE) gene. The APOE E4 allele increases risk for Alzheimer’s and is associated with an earlier age of disease onset. Some people with this allele, however, never develop the disease.

Rare variants in three genes are known to cause Alzheimer’s:

- Amyloid precursor protein (APP) on chromosome 21

- Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) on chromosome 14

- Presenilin 2 (PSEN2) on chromosome 1

A child whose biologic parent carries a genetic variant for one of these three genes has a 50/50 chance of inheriting that altered version of the gene.

When Alzheimer’s develops before age 65, it is known as early-onset Alzheimer’s or sometimes younger-onset Alzheimer’s. Less than 10% of all people with Alzheimer’s develop symptoms this early. Of those who do, 10% to 15% can be attributed to changes in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 (NIA, 2024a).

Down Syndrome and Alzheimer’s

People with Down syndrome have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s, and this is believed to be related to trisomy 21, which includes the gene that encodes for the production of APP, which in people with Alzheimer’s is cut into beta-amyloid fragments that accumulate into plaques. Amyloid accumulation is seen in almost all adults over age 40 with Down syndrome. Despite these brain changes, however, not everyone with Down syndrome develops Alzheimer’s symptoms.

People with Down syndrome are also very likely to experience severe issues related to their heart, which places them at increased risk for early-onset dementia. Many people with Down syndrome are diagnosed with AD in their 50s, but it is not uncommon for symptoms to occur in the late 40s (CDC, 2022).

TREM2 and Chronic Inflammation in the Brain

The triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), a transmembrane receptor abundantly expressed on microglia, has been identified as one of the risk factors of AD.

Studies have demonstrated that the gene TREM2 R47H variant is a risk factor for AD. TREM2 promotes the seeding and spreading of tau aggregates in nerve plaques. TREM2 deficiency prevents microglia from aggregating around beta-amyloid deposits, causing senile plaques to spread more, thus increasing neuronal damage. TREM2 can not only influence microglial functions in amyloid and tau pathologies, but also participates in inflammatory responses and metabolism (Huang et al., 2023).

EPIGENETIC RISK FACTORS

Epigenetics (how certain genes are turned on and off) influences many complications at cellular and molecular levels, including Alzheimer’s disease.

Growing evidence points to epigenetic changes as playing a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of the disease. The dynamic interplay between genetic and environmental factors influences the epigenetic landscape in AD, altering gene expression patterns, key pathologic events associated with disease pathogenesis. To this end, epigenetic alterations not only impact the expression of genes implicated in AD pathogenesis but also contribute to the dysregulation of crucial cellular processes, including synaptic plasticity, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress.

In Alzheimer’s disease, the epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modification, and noncoding RNA, which alter gene expression at the transcription level by upregulation, downregulation, or silencing of genes that have a substantial impact on the progression and pathways linked to Alzheimer’s disease (DePlano et al., 2024).

Chronic Stress and Depression

Depression in known to be a risk factor for dementia, but Alzheimer’s may also be part of the disease itself. The connection is complicated, and how the two conditions are linked is unclear. Further research is needed to evaluate whether the link may be biologic; a result of behaviors associated with depression, such as social isolation and other changes in key health behaviors; or some combination of these mechanisms.

It is not fully understood whether the length of depression, the severity of depression, or the age at which someone experiences depression affects their dementia risk. Research shows that depression can increase risk of dementia whether it occurs in early adulthood, midlife, or later life. It is important to note that, while there is a connection, not everyone who has depression will go on to develop dementia and not everyone with dementia will develop depression (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024d; Penn Medicine, 2023).

Chronic stress and depression are potential risk factors for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. A diagnosis of depression has been found to be associated with an approximately twofold increased risk for later Alzheimer’s disease. The risk increases further in patients who also experience chronic stress. This suggests that chronic stress and depression may be independent risk factors for dementia and that together they may have an additive effect on the risk for later dementia (Wallensten et al., 2023).

Diet

The risk of AD is known to be increased by diets high in table sugar (sucrose) or high-fructose corn syrup, high-glycemic-index carbohydrates, salty foods, and alcohol, as well as processed meats rich in umami flavor (savory, meaty, brothy, smoky, or earthy).

Results from a 2023 study suggest that Alzheimer’s disease could be a maladaptation of an evolutionary survival pathway mediated by intracerebral fructose and uric acid metabolism. High levels of fructose, particularly those derived from added sugars such as sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup, could alter brain metabolism and cause degeneration of brain regions associated with Alzheimer’s disease. A prolonged decline in metabolism in higher cognitive functions may cause degeneration of these regions and lead to the cognitive decline observed in Alzheimer’s disease (Johnson et al., 2023; Shukla, 2023).

Excess Deregulated Brain Iron

Iron excess has been found to be pivotal in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. In patients carrying the APOE4 allele, the increase in iron detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) has been found to be strongly associated with cognitive decline, indicating that iron imbalance can be one of the risk factors for AD. Iron overload and oxidative stress in the brains of people with AD have been associated with the aggregation of beta-amyloid-induced senile plaque deposition and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins that form neurofibrillary tangles in the brain (Levi et al., 2024).

Diabetes Mellitus

Scientists are finding more evidence that links type 2 diabetes with Alzheimer’s disease. Several research studies following large groups over many years suggest that adults with type 2 diabetes have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s. One study found that people with high blood sugar levels—such as those linked with type 2 diabetes—had a dramatic increase in beta-amyloid protein, one of the hallmark brain proteins of Alzheimer’s disease. Another study found that those whose onset of type 2 diabetes was at a younger age are at high risk of dementia. People with type 1 diabetes were found to be 93% more likely to develop dementia (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023b).

Cardiovascular Disease

Studies link Alzheimer’s disease with cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, inflammation, and dyslipidemia. One third of Alzheimer’s disease–related dementias are attributable to modifiable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as hypertension, which promote the accumulation of amyloid, a hallmark pathology in the brains of people with AD.

Atherosclerosis is associated with hypoxia, inflammation, oxidative stress, and the accumulation of advanced glycation end products, all of which are factors that can enhance the deposition and/or reduce clearance of amyloid in the brain. Atherosclerosis could contribute to brain dysfunction and axonal damage by a subtle reduction in microvascular perfusion without causing overt ischemic lesions. In addition, subclinical atherosclerosis in coronary, carotid, and femoral arteries has been linked with dementia and AD incidence.

Arteriosclerosis, marked by measures of pulse wave velocity (among others), is associated with cognitive impairment, and studies suggest that intracranial arteriosclerosis (the hardening of arteries due to calcification) may play a role in the etiology of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (Saeed et al., 2023).

Hearing Loss

People who develop hearing problems during midlife (ages 40–65) have an increased risk of developing dementia. Even low levels of hearing loss have been associated with increased dementia risk and a decrease in memory and thinking skills. Hearing loss has also been linked to quicker shrinkage of areas of the brain responsible for processing sounds and memories.

Peripheral hearing loss involves reduced abilities of the ears to detect sounds. This increases the person’s risk of developing dementia. Central hearing loss involves problems with processing sounds in the brain that are not correctable with hearing aids. This may be a very early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, as sound-processing parts of the brain are affected by the disease.

People with hearing problems may also be more likely to withdraw from social situations and become more isolated and depressed over time. Social isolation and depression are both risk factors for dementia.

The use of hearing aids has been shown to reduce the risk of dementia to the level of a person with normal hearing (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024c).

Head Trauma

Certain types of traumatic brain injury (TBI) have been found to increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s or other dementias years after the injury. Older adults with a history of moderate TBI have a 2.3 times greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s compared to older adults with no history of head injury. Those with a history of severe TBI have a 4.5 times greater risk.

The risk of a dementia diagnosis is highest during the first year following TBI. During this time people are four to six times as likely to develop a dementia diagnosis as those without TBI. One study found that a concussion or TBI can increase the risk of developing dementia even 30 years later.

Ongoing research is aimed at understanding the underlying mechanisms of the connection between TBI, cognitive decline, and dementia in the brain, including the role of potential exacerbating factors (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024f).

Smoking

Smoking is known to increase the risk of vascular problems, such as strokes or small bleeds in the brain, both of which are risk factors for dementia. Toxins in cigarette smoke also cause cell inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which of which have been linked to Alzheimer’s. Smoking may be responsible for 14% of Alzheimer’s cases worldwide. An analysis of 37 different studies suggested that current smokers are 30% more likely to develop dementia and 40% more likely to develop Alzheimer’s. In addition, the study found that smoking 20 cigarettes per day increases the risk of dementia by 34% (ALZRA, 2024).

Vitamin Deficiency

Low levels of vitamin D, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and folate have been found to increase the risk of dementia. Research suggests that people with very low levels of vitamin D are at higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Vitamin D is known to participate in the clearance of amyloid beta aggregates and may provide neuroprotection against amyloid beta-induced tau hyperphosphorylation. Low levels of serum vitamin D have been associated with a greater risk of dementia and AD (Ghahremani et al., 2023).

Obesity

Obesity (defined as having a body mass index of 30 or above) between the ages of 35 and 65 can increase dementia risk in later life by about 30%. Being overweight but not obese, however, does not carry the same risk. Obesity is also linked to other dementia risk factors. People with obesity are two to three times more likely to have high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. Obesity is also a risk factor for depression and is associated with social isolation and less physical activity—all of which contribute to the risk of dementia.

The size of a person’s brain begins to decrease naturally as they age. However, research has shown a relationship between BMI and brain size in people around age 60. The higher someone’s BMI, the smaller their brain. It has been suggested that the increased brain shrinkage associated with obesity ages the brain by around 10 years. Research has also shown that the areas of the brain that begin to shrink more in Alzheimer’s disease also shrink in people who are obese.

Obesity can lower a person’s resilience to the damage in the brain that Alzheimer’s disease causes, leading to worse symptoms and faster disease progression. Obesity can also lead to chronic inflammation in the body, causing the overactivation of immune cells in the brain, which leads them to damage the brain’s nerve cells (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024e).

Ophthalmic Comorbidities

Generally, visual impairment has been found to be associated with an increased incidence of dementia. Visual impairment increases dementia risk via several mechanisms similar to hearing impairments, such as increasing cognitive demands, leading to social isolation and physical inactivity, and even causing structural and functional changes in the brain. Several eye disorders, such as cataracts, age-related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy, are reported to be associated with AD and other dementias.

One study found that moderate-to-severe visual impairment could increase the risk of dementia by two times in the first two years and 1.8 times from two to four years of follow-up, although the association was not significant beyond four years. Studies also concluded that a more severe visual impairment was associated with a higher incidence of dementia (Zheng et al., 2024).

Hormones

Women make up an estimated 65% of people who currently have dementia. It is not fully understood why women are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia. One idea is that it may have to do with the hormone estrogen.

Research has shown that estrogen may help to protect the brain from Alzheimer’s by blocking some of the harmful effects of the amyloid-β protein. Estrogen can also affect the way chemical messengers such as serotonin, acetylcholine, and dopamine are used to send signals throughout the brain, and some Alzheimer’s disease symptoms are linked to these chemical messengers.

Alzheimer’s disease is more common in women after menopause, so it is possible that this protective effect may be lost when estrogen levels are decreased in older women. It is not clear whether hormone replacement therapy (HRT) reduces dementia risk or not, with some studies suggesting that estrogen may reduce dementia risk while others saying it increases the risk (Alzheimer’s Society, 2023a).

SEX

One’s sex plays a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease and involves both genetics and epigenetics. After advanced age, being female is the second major risk factor for Alzheimer’s. This may be due to differences in biology, such as menstruation, pregnancies, and menopause. It may also be related to traditional differences in gender roles, such as education, work, and lifestyle.

An important factor is that women who have the APOE4 gene variant have greater risk. Nearly two thirds of people with AD have at least one copy of this gene. Although men and women are just as likely to have the gene variant, its effect on dementia risk seems to be greater in women than in men. The reasons for this difference are not fully understood.

The expression of genes that contribute to the development of amyloid and tau pathology shows a female bias, and higher expression of these genes generates high amounts of protein involved in amyloid and tau pathology. Other characteristics, such having defective versions of neural survival factors, may contribute to women being more susceptible to developing AD (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024b; Reed-Geaghan, 2022).

Traumatic brain injury is another dementia risk factor where there may be important differences between the sexes, since women are more vulnerable to concussion and its long-term effects on the brain.

However, the vast majority of experiments and clinical trials carried out by dementia researchers have not been designed to find differences between male and female participants. Most older studies involving mice used only males, and the first phases of clinical trials recruited only male volunteers (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024b).

Possible Preventative Strategies

Currently, there is little definitive evidence about what can stop age-related cognitive decline and the onset of dementia, but more and more research suggests that attaining better brain health and resilience, even later in life, can postpone the critical moment when a change or effect becomes irreversible.

EXERCISE

Regular physical exercise may be a beneficial strategy to lower the risk of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Exercise may directly benefit brain cells by increasing blood and oxygen flow in the brain. Because of its known cardiovascular benefits, a medically approved exercise program is a valuable part of any overall wellness plan.

There are two main types of physical activity—aerobic and strength building. Each type has different benefits, and performing a combination of both types may help to reduce risk of dementia. Most studies report on the effects of aerobic exercise done several times a week and maintained for at least a year. Physical activity, however, can also mean a daily activity such as brisk walking, cleaning, or gardening. One study found that daily physical tasks such as cooking and washing up can reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024g; Alzheimer’s Society, 2024f).

DIET

The typical Western diet increases cardiovascular disease risk, possibly contributing to faster brain aging. It is possible that diet affects biologic mechanisms such as oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which underlie Alzheimer’s. Eating a certain diet might increase specific nutrients that may protect the brain through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, by inhibiting beta-amyloid deposits, or by improving cellular metabolism in ways that protect against the disease.

Research has shown, with mixed evidence, that two diets that may hold potential benefits for cognitive health:

- The Mediterranean diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, fish and other seafood, unsaturated fats such as olive oils, and low amounts of red meat, eggs, and sweets.

- The MIND (Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) diet is a hybrid of the Mediterranean and the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet. The MIND diet features vegetables, especially green leafy vegetables; berries over other fruit; whole grains; beans and nuts; one or more weekly servings of fish; and olive oil. It also limits servings of red meat, sweets, cheese, butter/margarine, and fast/fried food.

Other studies have shown that a molecule in green tea breaks apart tangles of the protein tau and that older adults who reported eating a daily serving of leafy green vegetables such as spinach or kale showed slower age-related cognitive decline, perhaps due to the neuroprotective effects of certain nutrients. Another recent study in mice found that consuming too much salt increased levels of the protein tau (NIA, 2023b).

SLEEP

Some evidence suggests that a lack of sleep may increase the risk of dementia, but researchers are not sure how sleep and dementia are linked. Does poor sleep increase dementia risk, does dementia lead to poor sleep, or both? One study found that nine or more hours sleep duration was associated with a 50% increase in Alzheimer’s mortality risk when compared to people who slept seven to eight hours, particularly in men. Additional studies are needed to further elucidate the mechanisms (Alzheimer’s Society, 2023b; Scheider et al., 2022).

PREVENTING HEAD TRAUMA

Because there is an association between traumatic head injury and an increased risk for Alzheimer’s dementia, it is important to take the following protective steps:

- Choose a sports program that enforces rules for safety and avoids drills and plays that increase the risk for head impacts.

- Wear a seat belt when driving or riding in a motor vehicle.

- Never drive while under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

- Wear a helmet or appropriate headgear when riding a bike or any other open vehicle and when taking part in any sport activities.

- Have a primary care provider or pharmacist review medications for safety concerns, including prescription medicines, over-the-counter medicines, herbal supplements, and vitamins.

- Have vision checked at least once a year and update eyeglasses if necessary.

- Perform appropriate-level strength and balance exercises.

- Make the home as safe as possible to prevent falls.

(CDC, 2024)

SOCIAL CONNECTIONS

It is difficult to know how much social isolation by itself contributes to the risk for dementia. Isolation might also occur as a consequence of dementia, and it is also tied to other risk factors, including physical inactivity and depression.

Social isolation can increase the risk of dementia by about 60%. Studies show that lifelong single people are more likely to develop dementia than those who are married. Widowed people are slightly more likely to develop dementia. Social isolation is less common in those who are married, as married people often have more social contact with others than single people.

Lonely people are more likely to drink heavily, smoke, not exercise, be overweight, and have heart problems, all of which increase the risk of dementia.

Engaging in social activities may help the brain’s ability to cope with disease, relieve stress, and improve mood. Examples can include:

- Adult education or learning

- Arts and crafts (especially in groups)

- Playing a musical instrument or singing

- Volunteering

(Alzheimer’s Society, 2024g)

VACCINATIONS

Several vaccines are associated with reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease in adults ages 65 and older. Some experts theorize that infection plays a role in developing Alzheimer’s disease and that vaccinations may help stave off these infections. Others say it is possible that vaccination may reduce an immune system function that attacks amyloid plaque as an invader.

Studies have found that patients who received at least one influenza vaccine during the follow-up period of four years were 40% less likely to develop Alzheimer’s compared to those who did not get the vaccine; that those who received an annual flu shot had the lowest rate of the disease; and that regular vaccination against tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough (pertussis), shingles, and pneumococcal pneumonia has been associated with a 25%–30% percent reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease in patients ages 54 and older.

These findings suggest that vaccination has a more general effect on the immune system that may reduce the risk for developing AD (Barkley, 2023; Cimons, 202; Hsu, 2023).

BRAIN TRAINING

Brain training can improve memory and thinking, but there is no strong evidence that brain training activities will reduce a person’s risk of developing dementia. People who regularly do intellectual activities throughout life have stronger thinking abilities, which give them skills that may protect them against losses that can occur through aging and disease (Alzheimer’s Society, 2024h).

ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The cardinal symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease include:

- Memory impairment

- Executive function and judgment/problem-solving impairment

- Behavioral and psychological symptoms

Memory Impairment

Early in the course of Alzheimer’s, individuals are usually aware of their memory deficit and may make notes to remember important things. Sooner or later the memory deficit is such that they may forget to check their notes. Later they may become frightened and apprehensive about their memory problems, causing them to feel depressed and discouraged. As the disease progresses, individuals lose insight into their memory deficit and are no longer aware of it. It is at this point that they require protection to remain safe.

The following are early signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease memory impairment compared to typical age-related changes.

| Memory Impairment with Alzheimer’s | Typical Age-Related Memory Changes |

|---|---|

| (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024h) | |

|

Memory loss that disrupts daily life:

|

Developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when the routine in disrupted |

Challenges in planning or solving problems:

|

Making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills |

|

Difficulty completing familiar tasks, such as:

|

Occasionally needing help to use household devices (e.g., microwave setting) or other technical or mechanical device |

|

Confusion about time and place:

|

Getting confused about the day of the week but figuring it out later |

|

Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships:

|

Vision changes related to cataracts or other age-related changes or diseases |

|

New problems with words in speaking or writing:

|

Sometimes having trouble finding the right word |

|

Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps:

|

Misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them |

|

Decreased or poor judgment:

|

Making a bad decision or mistake once in a while (e.g., neglecting to change the oil in the car) |

|

Withdrawal from work or social activities:

|

Sometimes feeling uninterested in family or social obligations |

|

Changes in mood and personality:

|

Developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted |

HOW MEMORIES ARE MADE

Memory is a multifaceted cognitive process involving different stages: encoding, consolidation, retrieving, and reconsolidation.

Encoding involves acquiring and processing information that is transformed into a neuronal representation suitable for storage. The information can be acquired through various channels, such as visual, auditory, olfactory, or tactile inputs.

The acquired sensory stimuli are converted into a format the brain can process and retain. Different factors such as attention, emotional significance, and repetition can influence the encoding process and determine the strength and durability of the resulting memory.

Consolidation includes the stabilization and integration of memory into long-term storage to increase resistance to interference and decay.

Retrieving is the process of retrieving stored information. One critical factor involved in retrieval is the type of hints or cues in the environment (McDermott & Roediger, 2024).

TYPES OF MEMORY AND ASSOCIATED AD SYMPTOMS

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease marked by deficits in episodic memory, working memory, and executive function.

Memory is a large part of a person’s identity, and there are different types. Each type uses a different network in the brain, and therefore, one type can be affected by disease or injury while another type functions normally. Memory systems are divided into two broad categories:

- Declarative memory allows us to explicitly recall or recognize past events as facts (i.e., “knowing what”). Recalling information from declarative memory involves some degree of conscious effort; information is consciously brought to mind and “declared.”

- Nondeclarative memory is different in that it is accessed without conscious thought. It can be triggered implicitly and is expressed through performance, such as the skill of riding a bike (i.e., “knowing how”). Another form of nondeclarative memory is the ability to improve one’s perception of the surrounding world through practice (called perceptual memory).

(LaFee, 2021)

Episodic Memory

Episodic memories are what most people think of as “memory” and include information about recent or past events and experiences. Typically, Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a decline in episodic memory. People with AD complain that they can’t remember events they’ve experienced, conversations they’ve had, or things they’ve done.

The hippocampus and surrounding structures in the temporal lobe are important in episodic memory and are part of an important network called the default mode network and made up of several brain areas including frontal and parietal regions. This network has been implicated in episodic memory functioning (UCSF, 2024a).

A person with dementia may experience “time shifting.” This is when a person’s current experience is that they are living at an earlier time in their life (Alzheimer’s Society, 2023c). This explains why individuals with AD eventually “live in the past,” such as wanting to milk the cows even though they haven’t lived on a farm for over 20 years, wanting to go to work even though they retired 30 years ago, etc. It also explains why they’re able to remember events many decades old but unable to remember what happened that morning.

Semantic Memory

Like episodic memory, semantic memory is declarative and refers to a person’s general knowledge, including common knowledge of facts about the world. It is also used to remember familiar faces or objects. Problems with semantic memory can include:

- Anomia, or the inability to find the right word. At first the person with Alzheimer’s is aware of this and may make up for it by using sentences to describe an object they cannot name. As the condition worsens, anomia comes to include common objects such as an eating utensil or pen.

- Aphasia, or difficulty with and eventual loss of the ability to speak or understand spoken, written, or sign language. In the advanced stage of the disease, speech becomes unintelligible, and eventually the person becomes mute.

- Agnosia, or loss of the ability to recognize what objects are and what they are used for. This may involve failing to recognize who people are. Agnosia can be visual, auditory, or tactile, but visual is the most common form.

(Blanchard, 2024)

Procedural Memory

Procedural memory is a form of nondeclarative memory, a type of long-term memory that stores information related to motor skills, habits, and actions that allow individuals to perform tasks automatically and without conscious effort. It involves learning and retention of procedures, routines, and how to execute specific actions.

The loss of procedural memory can result in difficulties carrying out routine activities such as dressing, bathing, and cooking.

Apraxia is one of the most common deficits in procedural memory observed in patients with Alzheimer’s. It is a disorder of “how” and “when” to correctly perform meaningful and purposeful actions. A person with apraxia is unable to put together the correct muscle movements, which can also lead to problems with speech. These may include:

- Ideomotor apraxia: the inability to act out a movement, such as turning a doorknob, even though one can describe how it is done

- Ideational apraxia: the inability to conceptualize and perform tasks that involve multiple sequential movements (such as putting on socks before shoes)

- Limb-kinetic apraxia: the inability to make precise, coordinated finger and hand movements (such as buttoning a shirt)

- Buccofacial/orofacial apraxia: the inability to perform facial movements on demand (such as licking lips, whistling, or winking)

- Verbal apraxia (apraxia of speech): difficulty coordinating mouth movements to produce speech

- Constructional apraxia: the inability to copy or draw objects or symbols

- Oculomotor apraxia: the inability to move the eyes on demand

(Gasnik, 2024; Simply Psychology, 2022)

Visuospatial Memory

Visuospatial memory gives one the ability to navigate in the environment and to identify, integrate, and analyze space and visual form, details, structure, and spatial relations in several dimensions. It requires the formation, storing, and retrieval of mental maps. In persons with Alzheimer’s, loss of this ability results in getting lost in familiar surroundings, wandering, and losing the ability to live independently (Kim & Lee, 2021).

Visuospatial ability examples include:

- Using a map to get from one place to another rather than relying on directions

- Walking through doorways rather than bumping into the door frames

- Driving or crossing the road; judging vehicle distance and speed accurately

- Looking at something and picking it up; guiding the hand accurately to the item wanted

A person with visuospatial problems finds it difficult to interpret what is being seen and to act appropriately.

Working Memory

Working memory can be defined as the ability of the brain to keep a limited amount of information available long enough to use it. Working memory helps process thoughts and plans as well as carry out ideas. It is the short-term memory that combines strategies and knowledge from the long-term memory bank to assist in making a decision or calculation. Working memory has been connected to executive functioning, which is often affected in the earlier stages of Alzheimer’s disease (Heerema, 2022a).

Executive Function, Judgment, and Problem-Solving Impairment in AD

Executive functioning refers to high-level cognitive skills required for control and coordination of other cognitive abilities and behaviors. Executive functions can be divided into organizational and regulatory abilities.

Organizational abilities are techniques used by individuals to facilitate the efficiency of future-oriented learning, problem-solving, and task completion. Organization requires the integration of several elements to reach a planned goal. These include:

- Attention: the capacity to be paying attention to a situation or task in spite of distractions, fatigue, or boredom

- Planning: the ability to create a mental roadmap to reach a goal or to complete a task

- Sequencing: the ability to perceive and execute a set of actions that follow a particular order

- Problem-solving: the capacity to identify and describe a problem, and generate solutions to fix it

- Working memory: the ability to hold information in mind while performing complex tasks

- Cognitive flexibility: the ability to revise plans in the face of obstacles, setbacks, new information, or mistakes

- Abstract thinking: the ability to think about objects, principles, and ideas that are not physically present

- Rule acquisition: how individuals acquire skill in applying problem-solving rules

- Selecting relevant sensory information: how an individual analyzes incoming sensory information in order to form visually guided motor decisions

Regulatory abilities involve evaluating available information and modulating a response to the environment. These include:

- Initiation of action: the ability to begin a task in a timely fashion

- Self-control: the ability to manage emotions in order to achieve goals, complete tasks, or control and direct behavior

- Emotional regulation: the ability to keep one’s emotions under control

- Monitoring of internal and external stimuli: the ability to monitor and change behavior as needed, plan future behavior when faced with new situations, and anticipate outcomes to changing situations

- Initiating and inhibiting context-specific behavior: the ability to inhibit or control impulsive (or automatic) responses and create responses by using attention and reasoning

- Moral reasoning: the logical process of determining whether an action is right or wrong

- Decision-making: the ability to be proficient in making choices between two or more alternatives

(UCSF, 2024b)

Damage to the executive system often leads to:

- Difficulty organizing

- Difficulty in planning and initiation

- Inability to multitask

- Difficulty with verbal fluency

- Trouble planning for the future

- Difficulty processing, storing, and/or retrieving information

- Mood swings

- Lack of concern for people and animals

- Loss of interest in activities

- Socially inappropriate behavior

- Inability to learn from consequences elating to past actions

- Difficulty with abstract concepts (the ability to make the leap from the symbolic to the real world)

- Unawareness or denial that their behavior is a problem

(UCSF, 2024b)

Early in Alzheimer’s, impairment of executive function can range from subtle to prominent. In many cases, the person underreports these symptoms, and an informant interview is critical. Family and coworkers may notice that the person is less organized or less motivated and that their ability to multitask is often impaired. In addition, the person develops poor insight and reduced ability for abstract reasoning. As Alzheimer’s progresses, the person becomes unable to complete tasks.

The patient with Alzheimer’s often has anosognosia, which is a reduced insight into one’s neurologic deficits. Many patients underestimate their deficits or try to offer explanations or alibis for them when they are pointed out by others. It is often a family member and not the patient who brings cognitive impairment to the attention of healthcare professionals. Loss of insight may be associated with behavioral disturbance. Those with relatively preserved insight are more likely to be depressed. Those with more impaired insight are likely to be agitated, be disinhibited, and exhibit psychotic features. Lack of insight can present problems with safety when patients attempt tasks they are no longer able to perform, such as driving (Wolk & Dickerson, 2024).

Psychological and Behavioral Symptoms in AD

Psychological and behavioral symptoms are common in Alzheimer’s disease, in particular during the middle and late stages of the illness. Psychological and behavioral symptoms affect up to 90% of patients diagnosed with dementia during the course of their illness. Patients with psychological and behavioral symptoms experience emotional distress, diminished quality of life, greater functional impairment, more frequent hospitalizations, increased risk of abuse and neglect, and decreased survival. Caregivers experience increased burden of stress and depression.

Some common psychological and behavioral changes are described in the table below:

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| (UCSF, 2024c) | |

| Apathy and indifference |

|

| Depression and dysphoria |

|

| Euphoria and elation |

|

| Anxiety |

|

| Irritability and lability |

|

| Inappropriate behaviors |

|

| Eating disorders |

|

| Sleep disturbances |

|

| Repetitive motor behaviors |

|

| Psychosis (during late-stage AD) |

|

Clinical Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Signs and Symptoms

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease go through different stages as the disease progresses and exhibit different signs and symptoms during each stage. The rate of progression of Alzheimer’s disease varies widely. On average, people with Alzheimer’s live between 3 and 11 years after diagnosis, but some survive 20 years or more.

Alzheimer’s disease has been classified into either three, four, five, or seven stages used for determining the level of care the person requires and for comparing groups of such patients with one another. These classifications are somewhat arbitrary, and there is a great deal of overlap among the various stages. One of the most commonly used classifications divides the disease process into five stages.

STAGE 1: PRECLINICAL ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease brain changes begin long before any symptoms become apparent. This stage is called preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. During this stage of the disease there are no noticeable symptoms either to the person with the disease or those around them. This stage can last for years, and even decades, before symptoms begin to appear and a diagnosis is made. This stage is usually identified only in research settings.

STAGE 2: MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

During this stage, minor changes in memory and thinking ability develop that are not significant enough to affect work or relationships. The person may have memory lapses when dealing with information that is usually easily remembered, such as conversations, recent events, or appointments. The person in this stage may also have trouble judging time required for completing a task and judging correctly the number of sequences of steps needed to complete a task. Making good decisions may become harder for people during this stage.

Other problems during this stage may include:

- Remembering names

- Recalling recent events

- Remembering where one put a valuable object

- Making plans

- Staying organized

- Managing money

- Remembering material that was just read

- Planning

The person may be aware of memory lapses, and their friends, family, or neighbors may also notice these difficulties.

STAGE 3: MILD DEMENTIA DUE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Alzheimer’s disease is often diagnosed in this stage when it is clear to family and healthcare professionals that a person is having significant problems with memory and thinking that impact daily functioning. During this stage, the person may experience:

- Memory loss for recent events

- Difficulty with problem-solving, complex tasks, and sound judgment

- Changes in personality

- Difficulty organizing and expressing thoughts

- Misplacing belongings

- Getting lost

STAGE 4: MODERATE DEMENTIA DUE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

During this stage, which lasts from 2 to 10 years and is the longest stage, the person becomes more confused and forgetful and begins to require some assistance with daily activities and self-care. The person may experience:

- Increasing trouble planning complicated activities (e.g., preparing a dinner)

- Trouble remembering remote events as well as recent memories

- Problems learning new things

- Trouble remembering their own name

- Being unable to recall information about themselves, such as their address or phone number

- Problems with reading, writing, and working with numbers

As the disease progresses, the person may:

- Know that some people are familiar but cannot remember their names

- Forget the names of a spouse or child

- Lose track of time and place

- Need help with daily self-care activities

- Become moody or withdrawn

- Have personality changes

- Be restless, agitated, anxious, or tearful, especially in late afternoon or at night

- Become aggressive

- Experience sleep problems

- Wander away from home

- Develop psychotic symptoms including hallucinations, paranoia, or delusions

- Lose impulse control

STAGE 5: SEVERE DEMENTIA DUE TO ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

During this stage of the disease mental functioning continues to decline, and the person loses the ability to communicate coherently. Severe impairment of all cognitive functions occurs, and at this point the person requires total assistance with personal care. As the disease continues to progress the person may remain in bed most or all of the time as the body begins to shut down, and the following may occur:

- Loss of physical abilities, including walking, sitting, and eating

- Inability to hold the head up without support

- Muscles becoming rigid and reflexing abnormally

- Ability to say some words or phrases but inability to have a conversation

- Becoming unaware of recent experiences and surroundings

- Needing help with all activities all of the time

- Becoming unable to recognize immediate family members

- Experiencing seizures

- Increased susceptibility to infection, especially pneumonia

- Sleeping an increased amount

- Losing bladder and bowel control

- Having impaired swallowing (which can lead to aspiration pneumonia, the most common cause of death in persons with Alzheimer’s disease)

(Mayo Clinic, 2023; Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2021a)

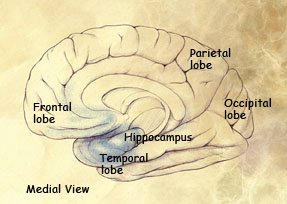

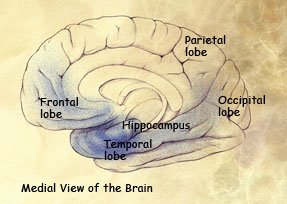

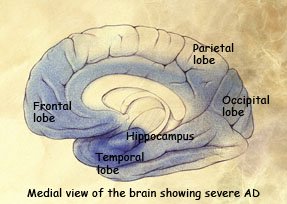

AREAS OF THE BRAIN AFFECTED DURING THE STAGES OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Preclinical stage: Areas of early damage to the hippocampus and portions of the frontal lobe (in blue).

Mild to moderate stages: Spread of damage forward into the frontal lobe and backward into the temporal lobe.

Severe stage: Extensive damage to areas during the final stage of Alzheimer’s disease.

(Source: National Institute on Aging.)

DIAGNOSING ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is usually made during the early stage, when the person appears to be physically healthy but is having increasing difficulty making sense of the environment. The affected person and the family may mistake early signs of Alzheimer’s for normal age-related changes. Deciding to seek diagnostic testing can be a major hurdle for the person and the family. Admitting that there may be the possibility of a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease can be difficult to accept.

There is no single test that can diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. Various approaches and tools are used to assist in making a diagnosis. Diagnosis is made using the following tools:

- Patient medical history

- Physical examination

- Neurologic examination

- Mental cognitive status tests

- Diagnostic tests (to rule out other health issues that can cause similar symptoms to dementia)

- Brain imaging

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024i)

Patient Medical History

The patient medical history helps to assess past and current health status and includes:

- Patient age and gender

- Chief complaint

- History of the current complaint

- Past medical history

- Current health status

- Psychosocial history such as marital status, living conditions, employment, sexual history, significant life events, diet, nutrition, and use of alcohol or other drugs

- Family medical history, including Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias

- Review of systems to ask questions about current symptoms not included in the chief complaint

- Mood assessment to detect depression or other mood disorders that can cause memory problems, apathy, and other symptoms that can overlap with dementia

- Psychiatric history and history of cognitive and behavioral changes

- Review of all medications

(Alzheimer’s Association, 2024i)

Physical and Neurologic Examinations

The physical and neurologic examinations enable the clinician to assess the overall physical and neurologic condition of the patient and provide more information about the current problem, helping to determine an appropriate plan of treatment. The physical exam may be a complete head-to-toe exam or a more focused examination, depending on the chief complaint. It generally includes:

- Overall appearance

- Vital signs

- Heart and lungs

- Head and neck

- Abdominal exam

- Extremities

- Blood test (see “Diagnostic Testing” below)

- Urine test (to detect formic acid levels, a sensitive biomarker for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease)

(News-Medical.Net. 2024)

The neurologic examination involves evaluating the person for problems that may suggest brain disorders other than Alzheimer’s, which could include Parkinson’s disease, brain tumors, or buildup of fluid in the brain. Family members may be asked to provide input about changes in the person’s thinking skills and behavior. The exam includes:

- Cranial nerve testing

- Reflex testing

- Coordination

- Motor function and balance

- Gait

- Speech

- Muscle tone and strength

- Eye movement

- Sensation

The neurologic exam may also include a fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET imaging study (Alzheimer’s Association, 2024i; Mayo Clinic, 2024).

Mental Cognitive Status Testing

The mental status examination can be divided into the broad categories of:

- Appearance

- Behavior

- Motor activity

- Speech

- Mood

- Affect

- Thought process

- Thought content

- Perceptual disturbances

- Cognition

- Insight

- Judgment

(Voss & Das, 2024)

Many screening tools are available, and the following are particularly useful.

MINI-MENTAL STATUS EXAM (MMSE)

The Mini-Mental State Exam is the most popular and well known of mental status screening tests. It assesses multiple cognitive domains, particularly memory and language, which may be most relevant to dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. The MMSE can be performed in a relatively short time period (5–10 minutes) and is most sensitive to patients at the moderate stage of Alzheimer’s dementia. It covers a wide range of functions, including memory, attention, orientation, and overall executive function. The tool consists of brief questions and simple tasks scored on a 30-point scale. A score below 24 is considered indicative of dementia.

Advantages of the MMSE include that it estimates the stage and severity of dementia for someone with the disease and that it can show changes over time. In addition, it is easy to administer and requires no special equipment or training.

The disadvantages of the MMSE include that it is less reliable. An educated person with dementia, for instance, might be able to score above 24. It also is not sensitive to mild cognitive impairment or early dementia. The MMSE requires a certain level of education in the patient; someone below an eighth-grade level of education should not take the Mini-Mental State Exam because low educational experience can lead to a misdiagnosis (Dementia Care Central, 2024).

MMSE QUESTIONS AND SCORING

During the MMSE, a health professional asks the patient the following questions or instructs the patient to perform a task:

- What is the date today? (3 points)

- What is the season? (1 point)

- What day of the week is it? (1 point)

- What town, state, and country are we in? (3 points)

- What is the name of this place? (1 point)

- What floor of the building are we on? (1 point)