A Look at Suicide: Prevention Training Program for Washington Healthcare Professionals (3 Hours)

Screening and Referral

Online Continuing Education Course

Course Description

3-hour mandatory suicide prevention training approved by the Washington State Department of Health. The following professions are required to take three hours of suicide prevention CE on suicide screening and referral: certified counselors and advisers, chemical dependence professionals, chiropractors, occupational therapists and assistants, physical therapists and assistants, and dental hygienists. This course meets the minimum requirements for pharmacists and dentists. Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc.'s training approval number is TRNG.TG.60722274-SUIC.

If you are in a crisis, call or text 988, call 911, or go to the nearest emergency room.

"This was an excellent course. Thank you!" - Danielle, RN in Washington

"Great course! Amazing information that will help me in private practice as well as in my personal life with friends and family members dealing with suicidal thoughts. Thanks!" - Jacklyn, student in Washington

"Great course and definitely worth it!" - Jacob, chiropractor in Washington

"Content was well organized, engaging, and concise. Very well done!" - Barbara, OT in Washington

A Look at Suicide: Prevention Training Program for Washington Healthcare Professionals (3 Hours)

Screening and Referral

Copyright © 2025 Wild Iris Medical Education, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

LEARNING OUTCOME AND OBJECTIVES: Upon completion of this continuing education course, you will demonstrate an understanding of the complex nature of suicide, how to assess and determine risk for suicide, and appropriate treatment and management for at-risk individuals. Specific learning objectives to address potential knowledge gaps include:

- Discuss the epidemiology and etiology of suicidal behavior.

- Summarize the risk and protective factors for suicide.

- Describe the process of assessment and determination of level of risk for suicide.

- Identify suicide prevention strategies.

- Discuss ethical dilemmas that arise in relation to suicide prevention and intervention efforts.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

UNDERSTANDING SUICIDE

Suicide is the culmination of many and varied interactions between biological, social, and psychological factors. Talk of suicide must always be taken seriously, recognizing that people with suicidal ideation are in physical and/or psychological pain and may have a treatable mental disorder. The vast majority of people who talk of suicide do not really want to die. They simply are in pain and want it to stop. Suicide is an attempt to solve this problem of intense pain when problem-solving skills are impaired in some manner, in particular by depression.

Healthcare professionals play a critical role in the recognition and prevention of suicide. However, many express concern that they are ill prepared to deal effectively with a patient who has suicidal thoughts. By developing adequate knowledge and skills, these professionals can overcome feelings of inadequacy that may otherwise prevent them from effectively responding to the suicide clues a patient may be sending, thereby allowing them to carry out appropriate screening and referral. They can also develop a better understanding of this choice that ends all choices.

EPIDEMIOLOGY IN WASHINGTON STATE

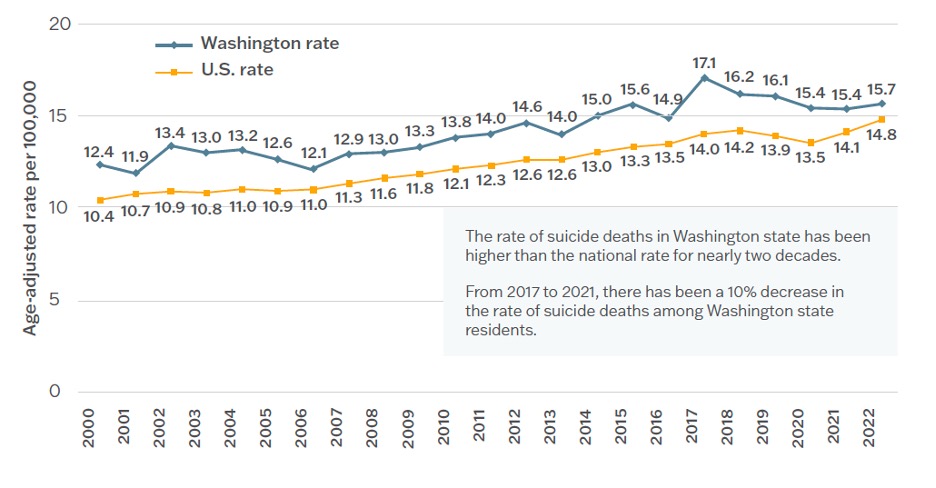

Suicide is a leading cause of death, particularly among young people, veterans, middle-aged men, and American Indian and Alaska Natives (AI/AN). Between 2018 and 2022, more than 1,200 Washington residents died by suicide each year, making it the eighth leading cause of death in the state. For nearly two decades, Washington’s suicide rate has consistently exceeded the national average. The economic and societal costs of suicide are also significant, estimated at over $12.8 billion annually in Washington alone (CDC, 2024).

By age: Suicide rates vary by age group. In 2022, suicide rates ranged from 1.75 per 100,000 among youth ages 10–14 years to 35.9 per 100,000 among people 85 years and older (WSDOH, 2025).

By race/ethnicity: Suicide rates by race and ethnicity point to additional disparities. Suicide rates ranged from 8.6 per 100,000 among non-Hispanic Asian populations to 22.0 per 100,000 among non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations. In 2022, 76% of suicides occurred among non-Hispanic White populations (WSDOH, 2025).

By sex: Suicide rates among females and males show large differences. In 2022, male age-adjusted suicide rates (23.6) were about four-fold higher than female rates (6.0) (WSDOH, 2025).

Age-adjusted suicide rates, 2000–2022, Washington and United States. (Source: WSDOH, 2025.)

SUICIDE ETIOLOGY AND RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS

Suicide etiology is complex and includes family history, genetics, epigenetics, neurobiology, medication use, and gender.

- Genetics: Four genes have been identified as heightening the risk of suicidal thoughts and actions.

- Epigenetics: The resulting impact of environmental influences on gene activity and expression has been associated with suicidal behavior.

- Neurobiology: Inflammatory mediators have been found to play a critical role in the pathophysiology of suicide.

- Medications: Certain antidepressants and anticonvulsant drugs can increase the risk for suicide.

- Gender: The rate of completed suicide in men is higher than in women; however, attempted suicide is more common among women than men.

Suicide Risk Factors

Risk factors for suicide may include:

- Family history of suicide or neuropsychiatric conditions

- Previous suicide attempt(s)

- Having a mental health disorder (e.g., depression, substance use disorder, PTSD, traumatic brain injury)

- Being a divorced or widowed female

- Socioeconomic factors (especially for men), including occupation, education, income

- Personality factors (e.g., paranoid personality features, obsessive-compulsive features)

- Developmental factors (e.g., behavioral disinhibition, negative emotional states)

- Life experiences, including history of trauma or abuse

- Impulsive/aggressive tendencies

- Cultural and religious factors

- Barriers to accessing mental health care

- Lack of or poor supportive social networks

(NV DPBH, 2021)

Suicide Protective Factors

Although there are many risk factors for suicide, there are also factors that protect people from making an attempt or dying by suicide. These protective factors are both personal and environmental.

Personal protective factors include:

- Values, attitudes, and norms that prohibit suicide, such as strong beliefs about the meaning and value of life

- Strong problem-solving skills

- Social skills, including conflict resolution and nonviolent ways of handling disputes

- Good health and access to mental and physical healthcare

- Strong connections to friends and family as well as supportive significant others

- Strong sense of cultural identity

- A healthy fear of risky behaviors and pain

- Optimism about the future and reasons for living

- Sobriety

- Medical compliance and a sense of the importance of health and wellness

- Good impulse control

- A strong sense of self-esteem or self-worth

- A sense of personal control or determination

- Strong coping skills and resiliency

- Being married or a parent

External/environmental protective factors include:

- Opportunities to participate in and contribute to school or community projects and activities

- Strong relationships, particularly with family members

- A reasonably safe and stable environment

- Availability of consistent and high-quality physical and behavioral healthcare

- Financial security

- Responsibilities and duties to others

- Cultural, religious, or moral objections to suicide

- Owning a pet

- Restricted access to lethal means

(CDC, 2022b)

Suicide Risk According to Age

Suicide occurs throughout the lifespan, affecting individuals in various age groups differently, and some have higher suicide rates than others.

CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among U.S. children and adolescents ages 10–19 years, causing more deaths than any single major illness and second only to unintentional injuries (CHA, 2023). The number of children ages 5–11 who have died by suicide has increased significantly between 1999 and 2020, most of these being children between 10–11 years old and 75% being male. Younger children who die by suicide are more likely to be of above-average intelligence, which possibly exposes them to the developmental level of stress experienced by older children.

Puberty may have a negative impact, especially for girls. Girls who mature early have been found to be more likely to have a lifetime history of disruptive behavior disorder and suicide attempts than their peers.

During adolescence, abstract and complex thinking begin to develop, and these youth become more capable of contemplating life circumstances, envisioning a hopeless future, generating suicide as a possible solution, and planning and executing a suicide attempt.

During adolescence, the prevalence of depression increases and becomes twice as high among girls than boys, which explains some differences in rates of suicide between boys and girls. As puberty progresses, most boys develop a positive self-image, but girls, particularly White girls, have a diminished sense of self-worth.

After puberty, the rate of suicide increases with increasing age. Potential reasons for this include an increased access to firearms and potentially lethal drugs; increased rates of psychiatric illness, substance abuse, and other comorbidities; or a history of aggressive, impulsive conduct with a tendency to act out emotions in damaging ways.

The risk of suicide among children and adolescents is increased due to:

- Family tensions

- Emotional and physical abuse

- Violence

- Lack of family connectivity

- Parental mental health problems

- Death of a loved one

- Family homelessness

- History of foster care and adoption

- Bullying

- Sexual orientation

- Substance abuse

(Kennebeck & Bonin, 2021; Sruthi, 2022; Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 2021)

SUICIDE IN ADOLESCENTS

Adolescents generally have a high suicide attempt rate, and those who are involved in certain subcultures have an even higher risk. For instance, there is an increased incidence of self-harm activities (such as cutting) in the “goth,” “emo,” and “punk” populations. Adolescents involved in repeated self-injury are up to eight times more likely to attempt suicide (Soreff, 2022).

It has been found that the rise in suicide and suicide attempts by adolescents correlates with the rise in electronic communication and social media. Increased digital media and smartphone use may influence mental health through several mechanisms, including the displacement of time spent in in-person social interactions, disruption of in-person social interactions, interference with sleep time and quality, cyberbullying, toxic online environments, and online information about self-harm (Twenge, 2020).

YOUNG ADULTS

Young adults experience mental health challenges at higher rates than any other age group. Close to half of those ages 18–24 struggle with mental health issues, and in 2021, 25.5% of young adults seriously considered suicide, including 10% of college students, and over 1,000 college students died by suicide. For specific ethnic and cultural groups, rates of suicide are even higher. Among American Indian and Alaska Native young adults, the rate of suicide is 2.5 times higher than that of their peers.

Many young adults continue to deal with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in high levels of depression, loneliness, anxiety, and trauma.

The top reasons for suicide among young adults include the following:

- Depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders

- History of substance abuse

- Exposure to violence, abuse, or other trauma, either chronic or acute

- Social isolation and loneliness

- Losing a family member through death or divorce

- Financial or job loss

- Conflict within relationships

- Starting or changing psychotropic medications

- Feeling stigmatized

- Lack of a support system

(Newport Institute, 2022)

MIDDLE-AGED ADULTS

Middle age (35–64 years) is a time of maximum risk, with suicide rates increasing in both middle-aged men and women, although men are much more likely than women to die by suicide. Middle-aged adults account for 47.2% of all suicides in the United States, and suicide is the ninth leading cause of death for this age group (CDC, 2022a).

Middle age is a period characterized by high familial and social expectations, increased self-confidence, leadership, and community contribution, making midlife a time of well-being and peak functioning as well as a time of high stress. Well-being during this phase of life can vary considerably, from being confident and resilient when meeting changes and difficulties, to being nervous or overanxious in response to stressful events and conflicts.

Suicide rates for middle-aged women have increased more quickly compared to rates for men in recent years. Many of these women are in the “sandwich” generation, those who take care of their children as well as older parents. They are more likely to be very stressed as a result of the responsibilities they carry, increasing their risk for suicide.

Unemployment has been found to be present in 43.2% of those who die by suicide in midlife and is associated with an almost fourfold increased risk of suicide. Separation and divorce increase suicide risk by more than three times. People in this age group, especially men, consider work position, employment, and marital relationship as indicators of their social identity, and problems in these areas can be deeply distressing (AACI, 2020; Qin et al., 2022).

DEATHS OF DESPAIR (DoD)

Over the past 20 years, there has been an increased mortality rate among middle-aged adults attributable to suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol abuse. These deaths are often referred to as “deaths of despair.” Socioeconomic factors related to these deaths include:

- Low socioeconomic position and education levels

- Working in jobs with high insecurity

- Unemployment

- Living in rural areas

(Beseran et al., 2022)

OLDER ADULTS

Adults ages 65 and older comprise just 12% of the population but make up approximately 18% of suicides. Men 65 and older face the highest overall rate of suicide. Older adults tend to plan suicide more carefully and are also more likely to use more lethal methods. Among people who attempt suicide, 1 in 4 older adults will succeed, compared to 1 in 200 youths. Even if an older adult survives a suicide attempt, they are less likely to recover from the effects.

Loneliness has been found to top the list of reasons for suicide among this age group. Many of them are homebound, live on their own, and may lack the social connections needed to thrive. Other reasons may include:

- Grief over the loss of family members and friends, and anxiety about their own death

- Loss of self-sufficiency and independence

- Greater likelihood of illnesses and chronic and/or debilitating diseases such as arthritis, cardiac problems, stroke, or diabetes, which compromise quality of life

- Loss of vision and hearing make it harder to do the things they’ve always enjoyed doing

- Cognitive impairment and dementia, which can affect a person’s decision-making abilities and increase impulsivity

- Financial stress, such as living on a fixed income and/or struggling to pay bills or afford food

- Clinical depression brought on by physical, emotional, and cognitive struggles

(NCOA, 2021)

Suicide Risk among Specific Populations

Although suicide affects all groups of the population, the risk and protective factors for suicide may differ. The following summarizes risk and protective factors among specific populations.

PERSONS WITH DEMENTIA

Overall, people with dementia have no higher risk of dying by suicide than the general population, but the risk is significantly increased in three groups of people with dementia: those diagnosed before the age of 65, those in the first three months following diagnosis, and those with dementia and psychiatric comorbidity. In people younger than 65 years and within three months of diagnosis, suicide risk was seven times higher than in those without dementia.

Patients with early dementia may have greater cognition, giving them more insight into their disease and better enabling them to carry out a suicide plan. Severe dementia, however, could protect against suicide by decreasing a person’s capacity to implement a suicide plan. Also, impairment in cognition and personal activities of daily living are associated with greater risk of nursing home admission, which in itself is a risk factor for suicide (Alothman et al., 2022; Joshaghani et al., 2022).

CAREGIVERS

More than 21% of the U.S. population serves as caregivers to someone with an illness or disability. They are usually spouses, older children, parents, and family friends. Men and women equally share in the responsibility, which is fulfilled mostly by those ages 38–64. In 2020, 24% of caregivers were looking after more than one person. As a result of their significant social, economic, and personal contributions, caregivers experience high rates of physical and mental illness, social isolation, and financial distress. They are also at high risk for suicide.

In a U.S. study asking hospice and palliative social workers to identify patients and caregivers at risk for suicide in the previous year, 55.4% reported one or more caregivers who exhibited warning signs of suicide, 6.8% reported one caregiver who had attempted suicide, and 4.1% reported one caregiver who died by suicide (Herman & Parmar, 2022; O’Dwyer et al., 2021).

MILITARY SERVICE PERSONNEL

Suicides among military service personnel have been steadily rising during the past 10 years, and suicide is now the second-leading cause of death among this group. Greater than 90% of military suicides are by male personnel who are most often younger than 35 years of age. The most common method used for military personnel to die by suicide is a firearm.

In a study asking a group of active-duty soldiers why they tried to kill themselves, all of the soldiers indicated a desire to end intense emotional distress. Other common reasons included the urge to end chronic sadness, a means of escaping people, or a way to express desperation. In addition, rates of mental health problems have risen 65% in the military since 2000, with nearly one million troops diagnosed with at least one mental health issue. Risk for suicide increases when military personnel experience both depression and posttraumatic stress together (MSRC, 2022; ABCT, 2022).

Experiencing child abuse, being sexually victimized, and exhibiting suicidal behavior before enlistment are significant risk factors for service members and veterans, making them more vulnerable to suicidal behavior when coping with combat and multiple deployments. Military personnel reporting abuse as children have been found to be three to eight times more likely to report suicidal behavior. Sexual trauma of any type increases the risk for suicidal behavior. Men who have experienced sexual trauma are less likely than females to seek mental health care, which they may see as a threat to their masculinity. This is a strong predictor of suicide attempts in military personnel. Service members who attempted suicide before joining the military are six times more likely to attempt suicide post enlistment (APA, 2023).

Suicide among women in the military has increased at twice the rate of male service members. When compared to civilian women, those in the service are two to five times more likely to die by suicide. The primary reason is sexual trauma, particularly incidences of harassment and rape while stationed overseas, resulting from a pervading military culture that is antagonistic toward women in the military (Gorn, 2023).

There is strong evidence that among veterans who experienced combat trauma, the highest suicide risk has been observed in those who were wounded multiple times and/or were hospitalized as a result of being wounded.

Studies that looked specifically at combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) found that the most significant predictor of both suicide attempts and the preoccupation with thoughts of suicide is combat-related guilt about acts committed during times of war. Those with only some PTSD symptoms have been found to report hopelessness or suicidal ideation three times more often than those without PTSD (VA, 2022a).

SUICIDE SCREENING AND ASSESSMENT

Because a significant proportion of individuals who die by suicide have seen a health professional within a few days prior to their suicide attempt, suicide screening and assessment of risk for suicide are important steps to be taken in all healthcare settings.

Suicide prevention screening refers to a quick procedure in which a standardized instrument or tool is used to identify individuals who may be at risk for suicide and in need of assessment. It can be done independently or as part of a more comprehensive health or behavioral health screening. Suicide assessment, as opposed to screening, refers to a more comprehensive evaluation done by a clinician to confirm a suspected suicide risk, to estimate imminent danger, and to decide on a course of treatment.

Suicide Screening

There is debate about the benefits of screening all patients (universal screening) for suicide risk factors and whether screening actually reduces suicide deaths. The general view, however, is that such screening should only be undertaken if there is a strong commitment to provide treatment and follow-up, since there is some evidence that screening improves outcomes when it is associated with close follow-up and treatment. Instead of universal screening, some recommend that screening be done only for those presenting with known risk factors (selective or targeted screening). Despite this lack of uniform guidance, health systems are implementing suicide screening protocols, and screening tools are already widely used in primary care settings (O’Rourke et al., 2022).

U.S. PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATIONS

Previously the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concluded that there was insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care. The USPSTF, however, recommended screening for major depressive disorder in adolescents ages 12–18 years and in the general adult population, including pregnant and postpartum persons, noting that screening should be implemented with adequate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow up. The 2022 draft recommendation statements are consistent with these previous recommendations (USPSTF, 2022).

JOINT COMMISSION RECOMMENDATIONS

The Joint Commission requires that all individuals from age 12 and above in all medical settings be screened for suicidal ideation using a validated tool. Patients who are screened and found positive for suicide risk on the screening tool should receive a brief suicide safety assessment conducted by a trained clinician to determine whether a more comprehensive mental health evaluation is required (TJC, 2023).

AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PEDIATRICS

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ age recommendations for screening state:

- Youth ages 12 and over: Universal screening

- Youth ages 8–11: Screen when clinically indicated

- Youths under age 8: Screening not indicated; assess for suicidal thoughts/behaviors if warning signs are present

Young people require screening more frequently than adults, as adolescence and young adulthood are times of rapid developmental change, and circumstances can shift frequently (AAP, 2022).

SCREENING TOOLS

The following are validated, evidence-based suicide risk screening tools:

- Beck Fast Scan: Seven questions that can help determine the intensity and severity of depression

- Suicide Risk Screen: 10-item questionnaire often used to screen for suicide in young people

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ): Nine questions about self-harm, also used to identify patients at high risk of suicide

- SAFE-T: Can be used in an outpatient setting; offers insight into the extent and nature of suicidal thoughts and harmful behavior

- Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): Available in multiple languages for prehospital use to assess for the presence of harmful behavior; also assesses for any known suicide attempts and suicide ideations and behaviors

- Ask (ASQ) Suicide Screening: Four brief questions to screen medical patients ages 8 years and above

- SBQ-R: A psychological, four-item questionnaire to identify risk factors for suicide in adolescents and adults

(NIMH, 2022; Columbia University, 2021; CEBC, 2020)

Recognizing Suicide Warning Signs

Besides screening for risk factors for suicide, it is important to be able to recognize statements, behaviors, and moods that indicate an individual may be at immediate risk for suicide.

Statements by a patient that constitute a suicide warning sign include language about:

- Killing oneself

- Feeling hopeless

- Having no reason to live

- Being a burden to others

- Feeling trapped

- Having unbearable pain

Behaviors that may signal risk—especially when related to a painful event, loss, or change—include:

- Increased use of alcohol or drugs

- Searching for a method to end their life, e.g., online search

- Withdrawing from activities

- Risky behaviors

- Isolating from family and friends

- Sleeping too much or too little

- Visiting or calling people to say goodbye

- Giving away prized possessions

- Aggression

- Fatigue

- Writing a will and making final arrangements

People considering suicide often display one or more of the following moods:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Loss of interest

- Irritability

- Humiliation/shame

- Agitation/anger

- Relief/sudden improvement

(AFSP, 2023)

Suicide Risk Assessment

The purpose of a suicide risk assessment is to determine a patient’s risk and protective factors with a focus on identification of targets for intervention. The most effective assessment begins with the establishment of a therapeutic relationship with the patient.

ESTABLISHING RAPPORT

The initial contact with a person who has suicidal thoughts may occur in many different settings—home, telephone, inpatient unit, outpatient clinic, practitioner’s office, rehabilitation unit, long-term care facility, or hospital emergency department. Being skilled at establishing rapport quickly is essential for all clinicians. It is imperative that the person be given privacy, be shown courtesy and respect, and be made aware that the clinician wants to understand what has happened or is happening to them.

Basic Attending Skills

Basic attending and listening skills are valuable in establishing rapport and a therapeutic alliance in order to obtain information, set the foundation for the treatment plan, and assist in determining interventions. These skills range from nondirective listening behaviors to more active and complex ones.

Positive attending behaviors are nonverbal and include:

- Eye contact. Maintaining eye contact communicates care and understanding and can show empathy and an interest in the person’s situation. Cultures vary in what is considered appropriate. Asian and Native Americans, for example, may view eye contact as aggressive.

- Body language. Usually leaning slightly toward the patient and maintaining a relaxed but attentive posture is effective. This may also include mirroring, which involves matching the patient’s facial expression and body posture.

- Vocal qualities. These include tone and inflections of the interviewer’s voice. Tonal quality may move toward “pacing,” which is matching the patient’s vocal qualities. Vocal qualities can be used to lead the patient.

- Verbal tracking. This involves using words to demonstrate that the interviewer has accurately followed what the patient is saying, such as restating or summarizing what the patient has said.

Negative attending behaviors include:

- Overuse of positive attending behaviors, which can become negative or annoying

- Turning away from the patient

- Making infrequent eye contact

- Leaning back from the waist up

- Crossing the legs away from the patient

- Folding the arms across the chest

(Grieve, 2023)

Listening Skills and Action Responses

Effective interviewing also requires nondirective and directive listening as well as directive action responses.

Nondirective listening responses are described below:

- Silence is a skill requiring practice to be comfortable with. It is very nondirective, and if used appropriately, it can be very comforting for the patient.

- Nondirective questioning includes asking for clarification, more facts, and details, best done by using open-ended questions.

- Paraphrasing, or reflection, is a verbal tracking skill that involves restating or rewording what the patient has said. There are three types of paraphrasing that can be utilized:

- Simple paraphrasing gives direction but involves rephrasing the core meaning of what the patient has said.

- Sensory-based paraphrasing involves the interviewer using the patient’s sensory words in the paraphrase (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.).

- Metaphorical paraphrasing involves making an analogy or metaphor to summarize the patient’s core message.

- Intentionally directive paraphrasing is solution-focused and attempts to lead the patient toward more positive interpretations of reality.

- Empathizing is used to show that the listener identifies with the patient’s information and allows the patient the right to their feelings.

- Supporting includes agreement, offers to help, reassurance, and focusing on the here and now.

- Analyzing is helpful in gaining different alternatives and perspectives by offering an interpretation of the patient’s message, making sure the person will be receptive.

- Summarization is an informal summary of what the patient has said. It should be interactive, encouraging, and supportive, and include positives or strengths that may help the patient cope.

(Wrench et al., 2022)

Directive listening skills:

- Validating feelings involves acknowledgement and approval of the patient’s emotional state. It can help patients accept their feelings as normal or natural and can enhance rapport.

- Interpretive reflection of feeling, also referred to as advanced empathy, goes beyond surface feelings or emotions to uncover deeper, underlying feelings, which can bring about strong emotional insights or defensiveness.

- Interpretation, also known as reframing, is a classic psychoanalytic technique that can produce patient insight or a solution-focused way to help patients view their problems from a new and different perspective.

- Confrontation involves pointing out perceptual inaccuracies or inconsistencies to help the patient see reality more clearly. It works best when excellent rapport has been established, and it can be either gentle or harsh.

(Panna, 2020)

When attempting to elicit information from suicidal persons, it should be remembered that challenging or direct questions, which could be interpreted as critical, will rarely be of benefit. The individual who has suicidal thoughts should be encouraged and given the opportunity to express thoughts and feelings and be allowed to discharge pent-up and repressed emotions. Asking open-ended questions encourages the person to elaborate on their answers, which can provide important context on their level of risk, access to means, and presence of intent (Aamar, 2021).

| Person’s Statement | Appropriate Responses |

|---|---|

| Everyone will be better off without me. |

|

| I just can’t bear it anymore. |

|

| I just want to go to sleep and not deal with it again. |

|

| I want it to be over. |

|

| I won’t be a problem much longer. |

|

| Things will never work out. |

|

| It is all so meaningless. |

|

ASSESSING SUICIDAL INTENT

Once it is determined that suicidal ideations are present, the next step is to determine whether the patient has active (thoughts of taking action) or passive (wish or hope to die) intent. The patient should be asked if the thoughts are new and if there are changes in the frequency or intensity of chronic thoughts. It is also important to inquire about the patient’s ability to control these thoughts.

The next step is to determine if the patient has developed a suicide plan and their degree of intent. This includes asking whether or not they have made any preparations and what they are. It is also important to determine whether the patient has a history of impulsive behaviors or substance use that may increase impulsivity, and whether they have a past history of suicidal ideation and behavior.

In addition, the clinical interview includes observing whether the patient is disconnected, disengaged, or shows a lack of rapport, as these signs are associated with an increased risk of suicide (Schreiber & Culpepper, 2022).

Suicide Risk Assessment Tools

There are many tools available to assist healthcare professionals in determining suicidal intent. These assessment tools are used to assess a person’s intent to carry through. They are often used when positive results have been obtained with one of the screening tools mentioned above. The following are validated/evidence-based suicide risk assessment tools:

- Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), Risk Assessment version. The risk assessment version of this tool provides a checklist of protective and risk factors for suicide and is used along with the C-SSRS screening tool. It is appropriate in all settings for all ages and for special populations in different settings. The tool features a clinician-administered initial evaluation form, a “since last visit” version, and a self-report form. The Columbia protocol questions have also been incorporated into the SAMHSA SAFE-T model with recommended triage categories.

- Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSI). This 21-item self-report instrument can be used in inpatient and outpatient settings for detecting and measuring the current intensity of the patient’s specific attitude, behaviors, and plans to die by suicide during the preceding week. It assesses the wish to die, desire to make an active or passive suicide attempt, duration and frequency of ideation, sense of control over making an attempt, number of deterrents, and the amount of actual preparation for the contemplated attempt.

(TJC, 2023)

Clinical Interview

The clinical interview is the “gold standard” for suicide assessment and intervention. Topics covered during this interview include suicidal ideation, plans, self-control, intent, and safety planning.

There are three effective approaches to asking about suicide:

- Use a normalizing tone. About 60% of people who died by suicide denied suicidal ideation when asked by a healthcare provider, indicating the presence of psychological and interpersonal barriers to disclosure. It is helpful to use a statement that normalizes suicide ideation, such as: “I asked you this question because almost all people at one time or another have thoughts about suicide.”

- Use gentle assumption. To make it easier for patients to disclose suicidal ideation, the interviewer assumes that certain thoughts and behaviors are already occurring in the person and gently structures questions accordingly. So, instead of asking if the person has been thinking about suicide, ask “When was the last time you had thoughts about suicide?”

- Assess the person’s mood. An exploration of mood states might include asking permission to discuss mood, and then asking patients to rate their mood using a zero–10 scale. This is followed by questions that refer to the worst or lowest mood rating the person has ever had as well as what was happening at those times that made them feel so down. In order to end with a positive note, the patient is asked about the best mood rating they’ve ever had.

Explore suicidal ideation. When the patient discloses the presence of suicidal ideation, collaboratively explore the frequency, triggers, duration, and intensity of the suicidal thoughts. During this process, it is important to show curiosity, empathy, and interest instead of judgment. If the patient denies suicidal thoughts and the denial appears to be genuine, acknowledge and accept the denial, but if the denial seems forced or is combined with symptoms of depression or other risk factors, acknowledge and accept the denial but return to the topic later.

Explore suicide plans. Once rapport is established and the patient has talked about suicidal ideation, it is important to explore suicide plans. If patients admit to a plan, further exploration is crucial. Evaluation includes assessing the specificity of the plan, its lethality, availability of the means, and proximity of social support (i.e., availability of individuals who might intervene and rescue the patient) (see “Assessing the Plan, Lethality, and Risk” below).

Assess self-control. This requires asking directly about self-control and observing for agitation, arousal, or impulsivity. Arousal and agitation adversely affect self-control and are the inner push that drives persons toward suicidal acts (Sommers-Flanagan, 2022).

STEPS TO TAKE WHEN A PATIENT REFUSES ASSESSMENT

- Obtain information from other sources, such as:

- Collateral reports from staff

- Patient’s past medical records

- Past suicide attempts

- Past nonsuicidal self-injury

- Past episodes of suicidal thinking

- Mental status assessment

- For patients who are competent and refuse services, document efforts made to gain cooperation.

- Document an explanation of the limitations of assessment and how level of risk was determined.

(Obegi, 2021)

CASE

GRACE

Alex is an occupational therapist who received a referral from a primary care physician for a patient named Grace, who has trigeminal neuralgia. Trigeminal neuralgia is characterized by severe unilateral paroxysmal facial pain and often described by patients as the “world’s worst pain.” Alex is familiar with this syndrome and its label as the “Suicide Disease” because, even though the disease isn’t fatal, many afflicted with it take their own lives due to the intolerable and unbearable pain.

When Grace arrives for her first appointment, Alex quickly establishes rapport with her by using basic attending and listening skills. He reviews the disease process, describes what types of therapy he can offer, and discusses the aims of occupational therapy management in terms of adapting Grace’s activities of daily living in response to her pain and improving her quality of life. After performing Grace’s initial evaluation, Alex asks Grace to be involved in setting some realistic and meaningful short- and long-term goals for her treatment.

At each session throughout the course of Grace’s treatment, Alex engages her in conversation using open-ended questioning, during which he observes her and listens for red flags that may indicate suicidal thinking. During one session, he notices that she has become more withdrawn, appears sad and listless, and begins to talk about how she doesn’t think she can continue to deal with the pain much longer. Alex then asks her direct questions to screen her for suicide risk. After scoring the risk assessment tool, he contacts her physician for follow up.

Discussion

Alex has worked to establish a trusting relationship with Grace, and being aware of the potential outcome of this disorder, listens to her and observes her very carefully. When there is a change in her behavior and talk of feeling hopeless, he recognizes them as red flags and proceeds to screen her for suicide risk, asking the six questions included in the screening version of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Upon completion of the screening, he contacts her physician, who will determine management.

ASSESSING THE PLAN, LETHALITY, AND RISK

The evaluation of a suicide plan is extremely important in order to determine the degree of suicidal risk. When assessing the lethality of a plan, it is important to learn all the details about the plan, the method chosen, and the availability of means. People with definite plans for a time, place, and means are at high risk for suicide. Someone who is considering suicide without making a plan is at lower risk.

Suicidal deaths are more likely to occur when persons use highly damaging, fast-acting, and irreversible methods—such as jumping from heights or shooting—and do so when rescue is fruitless.

IMPULSIVITY AND SUICIDE

Some suicides are carefully planned and deliberate, while others appear to have been impulsively decided upon, involving little or no planning. Impulsiveness is thought to play an instrumental role in suicide because of the presumption that suicidal behaviors are carried out via rash decisions with little consideration for the consequences. A study of survivors of nearly lethal suicide attempts found that 1 in 4 individuals deliberated for less than 5 minutes. Another study found that 48% reported deliberating less than 10 minutes (HSPH, 2023a).

A recent study has found an altered pattern of ventromedial prefrontal cortex and frontoparietal connectivity in impulsive people who exhibit suicidal behavior, as well as reduced ventromedial prefrontal cortex value signals. This altered connectivity has been found to be disrupted in people who attempted suicide and is believed to underlie disrupted choice processes in a suicidal crisis (Wislowska-Stanek et al., 2021; Brown et al., 2020).

Methods of Suicide and Lethality

The desire for a painless method of suicide often leads individuals to choose a method that tends to be less lethal. This results in attempted suicides that do not end in death. For every 25 attempts, there is one death. For drug overdoses, the ratio is around 40 to 1.

The following are methods of suicide and the likelihood that they will result in death:

- Firearms: 82.5%

- Drowning/submersion: 65.9%

- Suffocation/hanging: 61.4%

- Gas poisoning: 41.5%

- Jumping: 34.5%

- Drug/poisoning: 1.5%

- Cutting/piercing: 1.2%

- Other: 8.0%

(HSPH, 2023b)

It is of utmost importance for clinicians to recognize that these methods, as well as other highly lethal suicide methods, are widely accessible and must be considered when determining the disposition of someone who has suicidal ideations.

Factors that influence the lethality of a chosen method include:

- Intrinsic deadliness. A gun is intrinsically more lethal than a bottle of pills.

- Ease of use. If a method requires technical knowledge, for example, it is less accessible than one that does not.

- Accessibility. Given the brief duration of some suicidal crises, a gun in the cabinet in the hall is a greater risk than a very high building 10 miles away.

- Ability to abort mid-attempt. More people start and stop mid-attempt than carry through. It is easier to interrupt a hanging or to call 911 after overdosing than to stop a method such as jumping off a bridge or using a gun.

- Acceptability to the individual. The method must be one that does not cause too much pain or suffering. For example, fire is readily accessible, but it is a method seldom used in the United States.

(HSPH, 2023b)

Level of Risk

A clinical judgment that is based on all the information obtained during assessment should help to assign a level of risk for suicide and determine the setting of care.

Patients who are low risk of suicide:

- Are experiencing recent suicidal ideation or thoughts

- Have no specific current suicide plan

- Have no clear intent to act

- Have not planned or rehearsed a suicide act

- Have identifiable and multiple protective factors

- Have limited risk factors

- Have no history of suicidal behaviors

- Have evidence of self-control

- Have supportive family members or significant others

- Have a high degree of ambivalence

Most people with suicidal ideation do not necessarily want to die; they just do not want to continue living in an intolerable situation or state of mind. This ambivalence is one of the most important tools for working with such persons. Almost everyone with suicidal thoughts is ambivalent about dying, leaning toward suicide at one moment in time, and then leaning toward living the next. The healthcare professional can use this ambivalence to help focus the person on the reasons why they should live.

Patients who are at moderate risk:

- Have current suicide ideation

- Have no clear plan for suicide

- Have had no preparatory behavioral or rehearsal of act

- Have limited or no intention to act

- Have limited identifiable protective factors

- Are able to control the impulse

- Have the ability to maintain safety, independent of external support

- Have no recent suicidal behavior

- Have supportive family or significant others

- Have a high degree of ambivalence

Patients who are at high/severe/imminent risk:

- Have strong, persistent suicidal ideation

- Have strong intention to plan or act

- Have a specific suicide plan

- Have access to lethal means

- Have minimal protective factors

- Have impaired judgment

- Have poor self-control either at baseline or due to substance use

- Have inability to maintain safety, independent of external support

- Have a poor social support network

- Have severe psychiatric symptoms and/or an acute precipitating event

- Have a history of prior suicide attempt

(VA, 2022b)

PREDICTING SUICIDE BY RISK LEVEL

There has been no improvement in the accuracy of predicting suicides in the past 40 years.

- 95% of “high-risk” patients will not die by suicide.

- 50% of suicides are from “low-risk” patients.

- 50% of individuals who complete suicide have no prior history of suicide attempts.

(PsychDB, 2021)

Differentiating between Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Suicide Attempt

Healthcare professionals are increasingly confronted with another problem related to suicide attempts called non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). DSM-5 defines NSSI as the “deliberate, self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially sanctioned” (APA, 2013).

Self-harm is a sign of emotional distress, and adolescents are at the highest risk, with approximately 15% of teenagers and 17%–35% of college students having been found to inflict self-harm injury. Both males and females have similar rates of NSSI. Studies have found the following reasons given for engaging in self-harm behavior:

- To feel a sense of control over the body or life situations

- To punish oneself for perceived faults

- To reduce negative emotions

- To feel “something” instead of numbness or emptiness

- To avoid certain social situations

- To receive social support

The greatest difference between suicide and self-harm is intent. Suicide is a method that can end pain, but self-harm is an act to enhance coping with feelings and stressors. Some individuals find that pain from self-injury is reassuring when they are feeling numb or disconnected from the world around them. NSSI, however, can increase the risk of suicide because of the emotional problems that trigger self-injury and the pattern of damaging the body in times of distress.

It is important to keep in mind that the act of self-harm induces pain receptors that trigger the brain to feel an adrenaline “rush.” This can readily become addictive and highly dangerous (Discovery Mood & Anxiety Program, 2023; Mayo Clinic, 2022).

Documentation of Suicide Risk Assessment

Good documentation is basic to clinical practice. Accurate, sufficiently detailed, and concise records of a patient’s treatment allow for quality care and communication among providers. The best records reflect awareness of risk and the process of professional judgement that recognized it, took steps to reduce it, and balanced it with patient needs. The following documentation should be present in the record:

- Reason for suicide assessment

- Review of past available records

- Evaluation of warning signs and risk and protective factors

- Initial and ongoing suicide risk assessment

- Access to lethal means and mitigation

- Consultations with colleagues

- Referrals to behavioral health

- Rationale and follow-up for treatment options

- Safety planning and discharge coordination

- Plans for follow-up

(Stefan, 2020)

MODELS OF CARE FOR PATIENTS AT RISK FOR SUICIDE

A model of care is a set of interventions that can be consistently carried out in various settings to ensure that people get the right care, at the right time, by the right provider or team, and in the right place. Newer models of care for management of patients at risk for suicide include:

- Crisis support and follow-up (e.g., center hotline)

- Brief intervention and follow-up

- Suicide-specific outpatient management

- Emergency respite care

- Tele–mental health

- Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, with suicide-specific treatment

(EDC, 2022)

Crisis Support and Follow-Up

Crisis support and follow-up can include mobile crisis teams, walk-in crisis clinics, hospital-based psychiatric emergency services, peer-based crisis services, and other programs designed to provide assessment, crisis stabilization, and referral to an appropriate level of ongoing care. Crisis centers can also serve as a connection to the patient between outpatient visits and are helpful for patients with barriers to accessing outpatient mental health services. Crisis services also include care coordination. Mobile crisis teams provide care in the community at the location of the person who has suicidal thoughts (EDC, 2022).

Brief Intervention and Follow-Up

Brief interventions range from a single, in-person session, to a computer-administered intervention in a primary care office, to an online screening and feedback intervention that can be done on a personal electronic device. Brief interventions can be an immediate intervention and also can be used in conjunction with any other level of care. Safety planning is recommended for those who refuse outpatient care. Outreach and follow-up are provided through phone calls, letters, and texts (EDC, 2022).

Suicide-Specific Outpatient Management

Suicide-specific outpatient management involves several sessions that may include dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive therapy for suicide prevention (CT-SP), and collaborative assessment and management of suicide (CAMS). It is critical that outpatient mental health providers monitor patients between appointments and follow up when patients miss appointments (EDC, 2022).

Emergency Respite Care

Emergency respite care is an alternative to inpatient or emergency department services for a person in a suicidal crisis when the person is not in immediate danger. Respite centers are usually located in residential facilities designed to be more like a home than a hospital. These facilities may include staff members who are peers who have lived experience of suicide. Respite care is increasingly being utilized as an intervention and may include help with establishing continuity of care and provision of longer-term support resources, as well as support by text, phone, or online following a stay (EDC, 2022).

Tele–Mental Health

Tele–mental health involves electronic communication to provide clinical mental health services from a distance. Healthcare organizations can use these services to provide emergency assessments and treatment, especially for those patients located in remote geographic regions and for organizations with limited access to mental health resources (EDC, 2022).

Hospitalization

Inpatient hospitalization is the most restrictive option for addressing suicide risk. Research has found that patients may be at higher risk immediately after discharge from inpatient care. The reasons why this may happen are not known; however, experts have questions as to whether there is something about the experience of hospitalization itself that may be harmful. Involuntary hospitalization has been found to be associated with increased risk of suicide both during the hospitalization and afterward. It is therefore recommended that hospitalization be carefully weighed against other options (EDC, 2022).

SUICIDE PREVENTION STRATEGIES

Effective suicide prevention is a comprehensive undertaking requiring the combined efforts of every healthcare provider and addressing different aspects of the problem. A model of this comprehensive approach includes:

- Identifying and assisting persons at risk. This may include suicide screening, teaching the warning signs of suicide, and providing gatekeeper training (see below).

- Ensuring access to effective mental health and suicide care and treatment in a timely manner and coordinating systems of care by reducing financial, cultural, and logistical barriers to care.

- Supporting safe transitions of care by formal referral protocols, interagency agreements, cross-training, follow-up contacts, rapid referrals, and patient and family education.

- Responding effectively to persons in crisis by ensuring crisis services are available that provide evaluation, stabilization, and referrals to ongoing care.

- Providing for immediate and long-term postvention to help respond effectively and compassionately to a suicide death, including intermediate and long-term supports for people bereaved by suicide (see “Postvention for Suicide Survivors” below).

- Reducing access to lethal means by educating families of those in crisis about safe storage of medications and firearms, distributing gun safety locks, changing medication packaging, and installing barriers on bridges.

- Enhancing life skills and resilience to prepare people to safely deal with challenges such as economic stress, divorce, physical illness, and aging. Skill training, mobile apps, and self-help materials can be considered.

- Promoting social connectedness and support to help protect people from suicide despite their risk factors. This can be accomplished through social programs and other activities that reduce isolation, promote a sense of belonging, and foster emotionally supportive relationships.

(SPRC, 2020a)

Public Health Suicide Prevention Strategies

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “Suicide Prevention Resource for Action” details the strategies based on the best available evidence to help states and communities prevent suicide.

- Strengthen economic supports

- Create protective environments

- Improve access and delivery of suicide care

- Promote healthy connections

- Teach coping and problem-solving skills

- Identify and support people at risk

- Lessen harms and prevent future risk

(CDC, 2022b)

GATEKEEPER TRAINING PROGRAMS

Gatekeeper training (GKT) is one of the most widely used suicide prevention strategies. It involves training people who are not necessarily clinicians to be able to identify individuals experiencing suicidality and refer them to appropriate services. GTK improves people’s knowledge, skills, and confidence in helping those who experience suicidal ideation and enhances positive beliefs about the efficacy of suicide prevention (Hawgood et al., 2023).

One example of gatekeeper training, QPR, involves three steps—Questions, Persuade, and Refer—that can be learned in as little as two hours (Purdue University, 2022).

VETERANS HEALTH ADMINISTRATION PREVENTION FRAMEWORK

Within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Veterans Health Administration’s approach to suicide prevention is based on a public health framework that focuses on intervention within populations rather than a clinical approach that intervenes with individuals.

This public health perspective considers questions such as:

- Where does the problem begin?

- How can we prevent it from occurring in the first place?

The VA follows this systematic approach:

- Define the problem by collecting data to determine the who, what, where, when, and how of suicide deaths.

- Identify and explore risk and protective factors using scientific research methods. Develop and test prevention strategies.

- Assure widespread adoption of strategies shown to be successful.

(VA, 2018)

Under the Veterans Comprehensive Prevention, Access to Care, and Treatment (COMPACT) Act of 2020, veterans in suicidal crisis can receive free emergency healthcare at any VA or non-VA healthcare facility (VA, 2023).

Resources available for veterans and their families include:

- Suicide Prevention Coordinator, available at each VA medical center, who provides veterans with counseling and other services; as appropriate, callers to the Veterans Crisis Line are referred to their local coordinator

- Coaching Into Care, a national telephone service to educate, support, and empower family members and friends seeking care or services for a veteran (call 888-823-7458)

- Veterans Crisis Line (call 988 or text 838255)

- Suicide Safety Plan template

- inTransition, a free, confidential program offering coaching and specialized assistance over the phone for active-duty service members, Guard and Reserve members, and veterans who need access to mental health care

- Make the Connection, an online resource that connects veterans, family members, friends, and other supports with information and solutions to issues affecting their lives

- Vet Centers’ readjustment counseling services

(VA, 2018)

Washington State Suicide Prevention Initiatives

Washington State’s first suicide prevention plan was written in 1995 by DOH and the University of Washington’s School of Nursing to address youth suicide prevention. That plan was revised in 2009 and again in 2014. Washington’s first comprehensive plan for suicide prevention for people of all ages was released in 2016, and the latest plan was released in 2025 and will extend through 2034.

The Washington Suicide Prevention Plan (WSDOH, 2025) is guided by five core principles:

- Centering lived experience

- Partnerships and collaborations

- Safe and effective messaging and reporting

- Evidence-based prevention

- Culturally informed approaches

Washington’s plan is further organized into four strategic directions, each with specific goals and objectives. These play an important part in a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention and align closely with the 2024 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention:

- Healthy and connected individuals, families, and communities

- Multisector suicide prevention

- Treatment and crisis services

- Data collection, quality improvement, and research

Forefront Suicide Prevention is a Center of Excellence at the University of Washington focused on reducing suicide. Forefront has trained more than 30,000 health and school professionals and community members statewide in suicide awareness, intervention, and response skills. Efforts include:

- LEARN Suicide Prevention, a training in suicide awareness, intervention, and response skills

- Forefront Community Organizers, a volunteer support network for those who have attempted suicide and those who have lost a loved one to suicide

- Forefront Cares peer-to-peer mentoring program for newly bereaved individuals

- Safer Homes, Suicide Aware, a campaign that focuses on safe storage of medications and firearms (see box below)

Reducing Access to Lethal Means

When a person is at risk for suicide, actions are required to removal lethal means. There are many actions that can be taken by families, organizations, healthcare providers, and policymakers to reduce access to lethal means of self-harm. Examples include reducing access to medications and safe storage of firearms.

Responsible firearm storage involves keeping them locked and preferably unloaded, and separating firearms and ammunition when not in use. Secure storage options include either storing firearms away from home or locked at home in a secure gun safe, gun cabinet, or lockbox. In addition, unloaded firearms can be secured with a gun-locking device or can be disassembled with parts securely locked in separate locations.

When considering temporary gun storage with friends or relatives, under federal law, a person should not ask someone to store their firearm if that person is prohibited from possessing a firearm.

Reducing means of suffocation includes taking measures to reduce suicide by hanging. About 10% of suicides by hanging occur in the controlled environments of hospitals, prisons, and police custody. The remainder occur in the community, where ligatures and ligature points are all widely available. Healthcare systems can reduce suicide by hanging by installing collapsible shower heads, light fixtures, door knobs, and providing bedding that is resistant to tearing.

Safety measures available for individual storage and disposal of prescription and nonprescription drugs include drug lockboxes, drug buyback programs, and confidential drug return programs. Many states, including Washington also have similar online tools to identify local collection sites and resources (NAASP, 2020). (See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

Collaborating with members of the community to increase public safety can include:

- Instituting lethal means counseling policies in health and behavioral healthcare settings and training healthcare providers in those settings

- Passing policies that exempt at-risk patients from 90-day refill policies

- Working with gun retailers and gun owner groups on suicide prevention efforts

- Distributing free or low-cost gun locks or gun safes

- Ensuring that bridges and high buildings have protective barriers

(SPRC, 2020d)

WASHINGTON’S SAFER HOMES, SUICIDE AWARE

In Washington, about 75% of gun deaths are suicides, and medication overdoses are the most frequent type of suicide attempt. Safer Homes, Suicide Aware, a program led by the University of Washington’s Forefront Suicide Prevention center, focuses on access to lethal means, particularly firearms and medications. The program targets men ages 35–64 and veterans, groups that are statistically more likely to use firearms in suicide attempts. Efforts include:

- Partnering with firearms retailers, medical providers, pharmacy professionals, and veteran-serving organizations to make sure each group understands its crucial role in preventing suicides.

- Engaging directly with community members at public events ranging from gun shows to National Night Out gatherings.

- Offering free locks in exchange for participation in a survey about secure storage practices and suicide risk awareness

(WSDOH, 2025)

Postvention for Suicide Survivors

All settings should incorporate postvention as a component of a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention. Postvention is a term often used in the suicide prevention field. It is an organized response in the aftermath of a suicide to accomplish any one or more of the following:

- To facilitate the healing of individuals from grief and stress of suicide loss

- To alleviate negative effects of exposure to suicide

- To prevent suicide among people who are at high risk after exposure to another’s suicide

Postvention ensures that individuals and families who have experienced a suicide and/or suicide attempt are offered support. Postvention activities are intended to normalize anger, minimize self-blame, help survivors find meaning in the victim’s life, and be sensitive to cultural differences regarding suicide.

Key principles for creating a comprehensive postvention effort include:

- Planning ahead to address individual and community needs

- Providing immediate and long-term support

- Tailoring responses and services to the unique needs of suicide-loss survivors

- Involving survivors of suicide loss in planning and implementing postvention efforts

All suicide prevention efforts should include a comprehensive postvention component that reduces risk and promotes healing for the immediate family and reaches out into the community to support the broader group of loss survivors, including friends, coworkers, first responders, treatment providers, and others exposed to the death (SPRC, 2020c).

INSURANCE COVERAGE FOLLOWING SUICIDE OR ATTEMPTED SUICIDE

There are federal protections to ensure that most health insurance plans will pay for medical care resulting from a suicide attempt. There are, however, many forms of health insurance, and some plans may expose people to substantial uncovered costs after an attempted suicide (NAMI, 2021).

Many people have life insurance policies. However, a suicide clause is a standard clause in life insurance policies that limits payments made to survivors of a policyholder who dies by suicide within a certain period after purchasing the policy. Insurance companies typically do not pay a death benefit if the covered person dies by suicide within the first two years of coverage, commonly known as the exclusion period.

When the exclusion period ends, the policy’s beneficiaries can receive a death benefit if the covered person dies by suicide (Cornell Law School, 2021).

POSTVENTION SERVICES AVAILABLE IN WASHINGTON STATE

Programs are available throughout Washington State to support people who have lost a loved one to suicide, such as Washington Support after Suicide, formerly known as CC Cares, offered by Crisis Connections. This program serves those newly bereaved by suicide. It was originally started and nurtured by Forefront Suicide Prevention at the University of Washington (Crisis Connections, 2025).

The Washington State Department of Health also lists many grief support resources on its website, such as the Healing Conversations Program for survivors of suicide loss. (See also “Resources” at the end of this course.)

POSTVENTION SUPPORT TO MILITARY FAMILIES

Military-sponsored programs for families and next of kin have been established to assist military dependents. Most commonly, a casualty assistance office works with them. Mental health and counseling services are available to all dependents, as are religious, financial, and legal services. A military family life consultant is available to work with the families.

- Casualty Assistance Program provides support for understanding all benefits and other forms of assistance.

- Veterans Affairs Bereavement Counseling offers bereavement support to parents, spouses, and children of active-duty and Guard or Reserve members who died while on military duty.

- Tragedy Assistant Program for Survivors (TAPS) is a national nonprofit veterans service organization that provides services to help stabilize family members in the immediate aftermath of a suicide.

- TRICARE provides mental health care services during bereavement; outpatient psychotherapy is covered for up to two sessions per week in a combination of individual, family, group, or collateral sessions.

- Bereavement camps and other groups for children include:

- Comfort Zone Camp

- The Dougy Center

- Eluna

- Good Grief Camps

- SnowballExpress

(TAPS, 2023; Military One Source, 2022)

ETHICAL ISSUES AND SUICIDE

Healthcare providers are guided by a code of ethics based on these principles:

- Autonomy: Respect for the individual’s self-determination

- Beneficence: Doing the greatest possible good

- Nonmaleficence: Preventing or minimizing harm

- Justice: Fairness and equal access to care

Suicide prevention, however, offers several ethical dilemmas. Emergent intervention may include:

- Actions taken without the individual’s consent

- Actions which limit a person’s freedom

- Actions which often feel and are disempowering

These challenge ethical imperatives, including:

- The right of a person to autonomous choice versus the need to protect vulnerable people (do no harm)

- Confidentiality versus the release or solicitation of information in order to prevent harm

- Freedom of choice to decide to live or die versus everything necessary should be done to preserve life

Involuntary hospitalizations and compulsory treatment can raise legal and ethical issues, as they violate basic civil rights, restrict the freedom of individuals, and impose significant responsibilities on physicians (see box below). This high sense of responsibility may cause physicians to cross their limits and ignore the autonomy of individuals while exercising their authority.

Healthcare providers’ duty to do no harm (nonmaleficence) can contradict the autonomy of a patient with suicidal ideation. Reporting suicide ideation to members of the healthcare team not providing direct care to a patient complies with the beneficence principle; however, this would breach patient confidentiality. This leads to a dilemma; neither can be chosen without violating the other.

The ethical principle of autonomy calls for respect, dignity, and choice, and therefore a person should not be coerced or manipulated into treatment if they are capable of autonomous decision-making. Taking away a person’s freedom when no crime has been committed is a very serious enterprise. Cases involving a suicidal patient are the classic example of what is considered justified involuntary hospitalization. However, there is ambivalence concerning this, and it is argued by some that the risk of suicide by itself may not be sufficient justification and can increase the risk of suicide following discharge.

Evidence is accumulating about harms inherent in civil commitment. Three arguments include:

- Inadequate attention has been given to the harms resulting from the use of coercion and the loss of autonomy.

- Inadequate evidence exists that involuntary hospitalization is an effective method to reduce deaths by suicide.

- Some patients with suicidal ideation may benefit more from therapeutic interventions that maximize and support autonomy and personal responsibility.

(Borecky et al., 2019; Colack et al., 2021)

INVOLUNTARY HOSPITALIZATION

Involuntary hospitalization (or commitment) means placing a person in a psychiatric hospital or unit without their consent. The laws governing involuntary hospitalization vary from state to state, but in general, they confine involuntary commitment to persons who are mentally ill and/or under the influence of drugs or alcohol and are deemed to be in imminent danger of harming themselves or others. In most states, an involuntary psychiatric commitment cannot extend beyond 72 hours without a formal hearing. This 3-day period allows patients to receive basic medical treatment.

According to Washington State Law, Title 71, Chapter 71.05 RCW, an individual can be involuntarily committed when the person refuses voluntary admission and the healthcare professionals “regard such person as presenting as a result of a behavioral health disorder an imminent likelihood of serious harm, or as presenting an imminent danger because of grave disability.” A petition is a legal request filed by a designated mental health professional for not more than 120 hours (5 days, excluding weekends and holidays) for evaluation and treatment before a probable cause hearing must be held. Following the 72-hour hold, if needed, a court hearing can result in additional commitments of 14, 90, or 180 days. The goal is to stabilize the patient sufficiently so that they can return to the community as quickly as possible (AFSP, 2022; Washington State Legislature, n.d.).

Differing Perspectives

There are several different perspectives when approaching the question of what should be done about a patient who has expressed verbally or by action the wish to die. Three such points of view are the libertarian, the communitarian, and the egalitarian-liberal perspectives.

The libertarian perspective is centered on the idea of autonomy and generally rejects involuntary hospitalization because it:

- Takes away the person’s freedom

- Restricts what the person can do with their body

- Prevents the person from protecting property (job, home)

- Is a means to manage people who do not adhere to social norms

- Coerces and manipulates patients into treatment

- Raises financial issues that may affect the patient and/or infringe on the property rights of other citizens (e.g., use of tax dollars)

- Does not recognize that suicide is sometimes a rational choice based on competent thought and decision-making skills

The communitarian perspective disregards the person’s autonomy and exclusively considers the community values of the clinician making the decision. It views suicide as morally wrong and offensive to the dominant group, and intervention must take place to prevent it.

The egalitarian-liberal perspective emphasizes the equality of access to resources. This approach states that the government’s role is to protect individual rights and that the right to health is a priority. If the right to health is not protected, then the rights of liberty and autonomy may not be possible. Involuntary hospitalization protects the person from a decision-impairing disease or disorder that puts the patient at risk for self-injury or death, and treatment of said disease or disorder gives the patient the right of health. However, the question remains as to how a mental health professional can know in advance that forcible treatment is justified, especially since there are no objective tests to verify whether or not a decision-impairing disease or disorder may or may not exist (Sandu et al., 2018).

CONCLUSION

Suicide—the deliberate ending of one’s own life—is an important public health concern. One important thing to consider is that most people are ambivalent about dying by suicide. They are caught in a situation from which they see no way out but to end their lives. This ambivalence is important, as it is the starting point at which an effective intervention can occur.

It is imperative that healthcare professionals understand the ways in which they can screen and assess individuals at risk of suicide and learn the skills necessary to effectively intervene and prevent a suicide from happening. These skills include:

- Recognizing who is at risk, especially those who may be at high risk in the near future

- Learning how to communicate openly with those suspected to be at risk

- Working with survivors of a suicide loss to help protect them from consequences such as taking their own lives, PTSD, and depression

- Providing suicide prevention education to others

RESOURCES

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention)

Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

988 (call or text)

800-273-TALK (8255)

Suicide prevention (National Institute of Mental Health)

Suicide Prevention Resource for Action (CDC)

Suicide resources (CDC)

Washington State

Safe medication return (WA State DOH)

Suicide prevention (WA State DOH)

Washington resources (Suicide Prevention Resource Center)

Washington suicide hotlines (Suicide.org)

REFERENCES

AACI. (2020). Healthy living blog-mental health and suicide rates in middle-aged adults. https://aaci.org/healthy-living-blog-mental-health-and-suicide-rates-in-middle-aged-adults/

Aamar R. (2021). Suicide risk assessment: How to talk about suicidal ideation. Relias. https://www.relias.com/blog/suicide-risk-assessment

Alothman D, Card T, Lewis S, et al. (2022). Risk of suicide after dementia diagnosis. JAMA, 79(11), 1148–54. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.3094

American Academia of Pediatrics (AAP). (2022). Screening for suicide risk in clinical practice. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/blueprint-for-youth-siuicide-prevention/strategies-for-clinical-settings-for-youth-suicide-prevention/screening-for-suicide-risk-in-clinical-practice/

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). (2023). Risk factors, protective factors and warning signs. https://afsp.org/risk-factors-protective-factors-and-warning-signs

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). (2022). Suicide claims more lives than war, murder, and natural disasters. https://supporting.afsp.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=cms.page&id=1226&eventID=5545

American Psychological Association (APA). (2023). Trauma before enlistment linked to high suicide rates among military personnel, veterans. https://www.socialworktoday.com/news/dn_081314.shtml

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. (ABCT). (2022). Military suicide. https://www.abct.org/fact-sheets/military-suicide/